The Heart of a Revolution: Philadelphia during the War for Independence

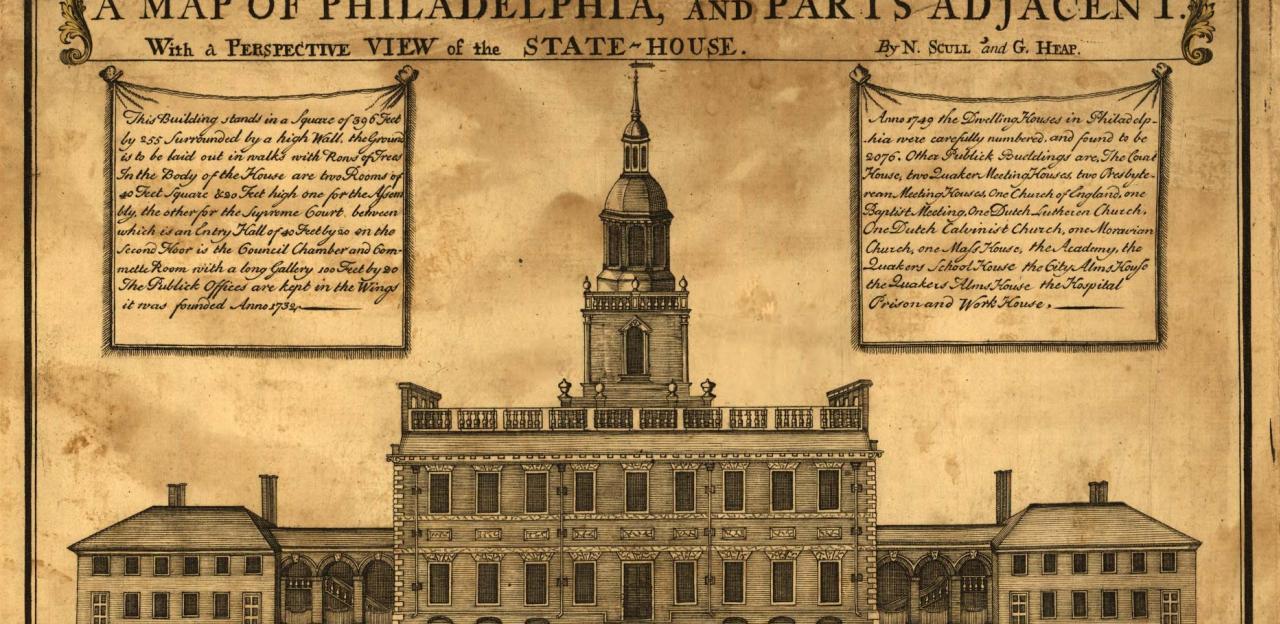

The city of Philadelphia was, in addition to being the largest city North America at the time, the spiritual heart of Revolutionary America. Philadelphia's Independence Hall played host to the Continental Congress. It too was where the Declaration of Independence was signed. Philadelphia was the home to some of the rebellion's most recognized proponents such as inventor turned patriot Benjamin Franklin. It is no surprise then that when war finally began, Continental officials worried that the British would immediately target the city while General George Washington was still consolidating his army. The constant fear of invasion looming over the city is evidenced in a series of hastily written intelligence reports sent from Pennsylvania President Thomas Wharton to his Safety Council. One of these reports, from November of 1776, urgently demanded that the militia be marshalled in the defense of the city immediately, reading, "We have certain Intelligence that the Enemy has actually sailed from New York Three Hundred ships for this City...As you value the Safety of your Country, and all that is dear and valuable to Men, we most earnestly solicit you immediate Assistance, and that you will march all your Battalion to this City without the least Delay." Though the dreaded invasion would not occur for the next few months, eventually Sir William Howe, the overall commander of British forces in North America, did strike out at Philadelphia in August of 1777 from his base in New Jersey in the hopes of drawing out Washington and defeating him on the open field. After a series of small skirmishes, the British finally did just that at the Battle of Brandywine that September, but though Howe inflicted heavy casualties on the American troops, he failed to destroy the Washington’s Army, which relocated to Lancaster along with the Continental Congress. Howe proceeded into Philadelphia unopposed, but though he successfully repulsed an American incursion on Germantown, he chose to remain there for the next few months.

The occupation of Philadelphia appears to have been difficult for those residents that remained. The city never contained much support for the Loyalist cause, and the soldiers did little to ingratiate themselves to the locals. Looting, though against Howe’s wishes, was frequent, even after discovering that Continental troops took most of the useful military supplies with them. Howe himself took up residence in the Masters-Penn House, which later became the President’s House under Washington and Adams, when Philadelphia was the capital of the United States. Although he had taken the city, Howe’s forces ended up failing to take control of the surrounding area, as many of his incursions were repulsed by skirmishes with Continental troops. During this time, Howe was either unable or unwilling to support his colleague and rival, General John Burgoyne, in upstate New York. Howe's petty squabbles ultimately led to Burgoyne's disastrous defeat at Saratoga, which not only emboldened the Continental Army but also secured French support for American independence. Meanwhile, Continental officials like Wharton continued to urge the people of Philadelphia to resist occupation and join up with their local militias in support of Washington. "With the blessing of Heaven, we have strength sufficient, if we will only exert it," one pamphlet decrees. "Let us then rise, like men, in earnest; let us not fall behind the other parts of the continent, but let the force of Pennsylvania be once more felt and acknowledged, as it often has been, by the enemy." The situation eventually became untenable for Howe and his troops, and the British finally abandoned the city in June of 1778 and returned to New York, having failed his objective of decisively defeating Washington and crushing Continental morale.

The Continental Congress quickly moved back into Philadelphia after the British abandoned the city. Benedict Arnold, still then a war hero after Saratoga, also took up residence in the house where Howe made his headquarters. While in Philadelphia, Arnold met a woman named Peggy Shippen, the daughter of prominent loyalist Edward Shippen. Arnold eventually married Peggy, and it was through her and her father that he began his treasonous correspondence with the British. After Arnold's betrayal was revealed to the world, Peggy would move with him to England after the war. Though fighting in Pennsylvania and the surrounding colonies would continue until 1780, any plans to recapture Philadelphia were abandoned and the city would remain an important location for governing the independent colonies until the founding of Washington D.C.

Learn More: Philadelphia Campaign