19th Century photographs of Revolutionary War veterans.

The Treaty of Paris in 1783 secured American independence, ending eight years of the American Revolutionary War. However, insecurity troubled the future for the many veterans of the Continental Army that received their discharges and returned home. The Continental Congress lacked money, and their promises of land in exchange for military service were not guaranteed either. The pieces of paper—called promissory notes, a promise for future payment— turned out to be worthless in the months and years to follow. Those internal uncertainties were coupled with returning to town, farms and businesses left in the care of family or vacant for years. What sort of homecoming greeted these veterans of places like Monmouth, New York, Yorktown, Valley Forge and the Southern Campaigns?

In today’s world, veterans’ organizations and services are common and support the transition from military to civilian life. In the 18th Century, the experience for many of the common soldiers was vastly different. Joseph Plumb Martin, whose diary is often quoted to get a glimpse of the common soldier’s experience, wrote this about the end of his service: “When the country had drained the last drop of service it could screw out of the poor soldiers, they were turned adrift like old worn out horses, and nothing said about land to pasture them upon.”

Although Martin’s very descriptive memory is not entirely accurate, the picture was bleak. Daniel Shays, whose surname gave title to one of the most famous rebellions of the early American republic, (Shays' Rebellion) is another testament to the experience of returning veterans. Shays received a court summons for unpaid debts, but he could not pay his bills and expenses because he had not received his military pay during or after the war. Many veterans sold the promissory notes at a mere fraction of their worth, just to buy essentials. This left little to no money for rent or loan payments. This resulted in the veterans’ taking matters of recourse into their own hands—like Shays who led a revolt in 1786 and 1787 in Massachusetts.

Matters continued to be unresolved until 1818 when a veteran of the American Revolution and the fifth president of the United States, James Monroe, signed a veteran’s pension legislation into law. The requirements of this legislation also imposed restrictions to apply for pensions and compensation. A veteran must have served at least nine months in the Continental Army or Navy and prove they were in “reduced circumstances.” This directive ignored those who served in state militias, short-term enlistment veterans and those not in abject poverty. The response overwhelmed the Federal government, with over 20,000 veterans having applied by November 1818. Two years later, Congress added another wrinkle and forced prospective pensioners to reapply, this time proving their financial need by providing a list of possessions and an explanation of why they could not earn enough income to support themselves. Finally, in 1832, the Federal government passed the Pension Act, enabling all former soldiers, regardless of service time, economic health or whether they had served in the Continental service or state service. All the veterans had to do was to appear in court, vouch—beyond a reasonable doubt—that they had served. This though was 35 years after the conclusion of the war. Letters from comrades, former commanders or neighbors could help the cause as well. If widows proved a wedding date, they could collect the pension of their later spouses as well. By the middle of the 19th Century, over 80,00 former Revolutionary War soldiers and/or their widows, including one widower on record, had applied for a pension.

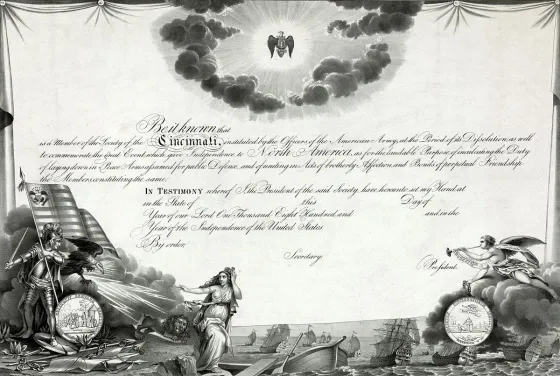

For officers, the experience could be quite different. In 1783, the Society of Cincinnati, a fraternal and hereditary society, was formed. Established for veteran officers of the American Revolution to enshrine “the remembrance of this vast event [the American Revolution]” and to “preserve inviolate those exalted rights and liberties of human nature.” The name Cincinnati hails from the Roman statemen and general Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus who after given dictatorial level power and winning a pivotal engagement voluntarily gave up power and returned to farming. Major General Henry Knox created the idea of the society, and the first meeting was held in May 1783 with the hope that the society and its members and offspring will “render permanent the cordial affection subsisting among the officers” that had served in the Continental Army. The society faced some criticism, with the fear that a society such as this had the markings of creating a hereditary nobility in the now independent United States. This was further exacerbated by the rules of admittance into society, exclusion of enlisted and militia officers and eligibility through primogeniture.

The American Revolution also saw its share of veterans returning with physical and mental wounds from their experiences. Eighteenth Century descriptive words such as “lost” or “bewildered” or “delirious” in their nature and personas equate with suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder, better understood in modern times. In a striking study of pension records from 1820, one historian concluded that disabilities did not differentiate the level of economic distress from those with non-disabling mental or physical wounds. Records are nonexistent or vague, but one can surmise that veterans of the American Revolution wounded in service, faced more barriers for work and economic sufficiency.

It took decades for the Federal government to pass and approve pensions, for those not disabled in the years of conflict. When those pensions were finally approved the pensions were the “first…paid to veterans without regard to rank, financial distress, or physical disability…” according to the Society of Cincinnati history. Furthermore, according to the historians of that society, the pensions “reflected the gratitude of a free people for the brave Americans who secured their freedom.” Long overdue but richly deserved by the patriots of 1776-1783.

Further Reading:

- Suffering Soldiers: Revolutionary War Veterans, Moral Sentiment, and Political Culture in the Early Republic by John Resch (University of Massachusetts Press, 2000)

- America's First Veterans by Jack D. Warren, Jr. (American Revolution Institute of the Society of the Cincinnati, 2020)

- The Last Muster: Faces of the American Revolution by Maureen Alice Taylor (Kent State University Press, 2013)