By Jason R. Wickersty

In 1776, hard fighting took place between the armies of General George Washington and General William Howe in Revolutionary War New York. Today, just few traces remain.

As the American and British forces were ensconced in and around Boston in the early months of 1776, both the besieger, General George Washington, and the besieged, General William Howe, saw New York as a “post of infinite importance.” John Adams described both the city and state as “a kind of key to the whole continent,” for which “no effort to secure it ought to be omitted.”

To Howe, capturing New York meant the ability to extricate his army from the hostile American position and populace of Boston. Thanks in part to royal governors in New York and New Jersey who remained active in trying to contain support for the rebellion, he could count on a citizenry more loyal to the Crown than Congress. Moreover, the deep, sheltered waters of New York Harbor could provide an ideal base of operations for the Royal Navy — command of the Hudson River would effectively cut off New England, the hotbed of the Revolution.

To thwart all this, Washington dispatched his second in command, General Charles Lee, to prepare New York for an eventual British invasion. He sought to make any British victory a pyrrhic one, and to turn the city into an “advantageous field of battle” for the Americans. When Howe abandoned Boston for Nova Scotia on St. Patrick’s Day 1776, the Continental Army joined the troops throwing up earthworks and redoubts on the heights of Brooklyn, Manhattan and the New Jersey Palisades. Writing to his brother John, General Washington offered a blunt assessment of the situation: “We expect a very bloody summer at New-York … and I am sorry to say that we are not, either in men or arms, prepared for it.”

On July 2, even as the Continental Congress was voting on independence in Philadelphia, the first ships of the armada carrying Howe’s army sailed unopposed into New York Harbor. Through July and August, their numbers grew, the greatest British expeditionary force of the 18th century transforming Staten Island into the second largest city in North America. To an American soldier on duty at the Battery in Manhattan, the harbor appeared so crammed with ships that he “thought all London was afloat.” It was shock and awe in every sense.

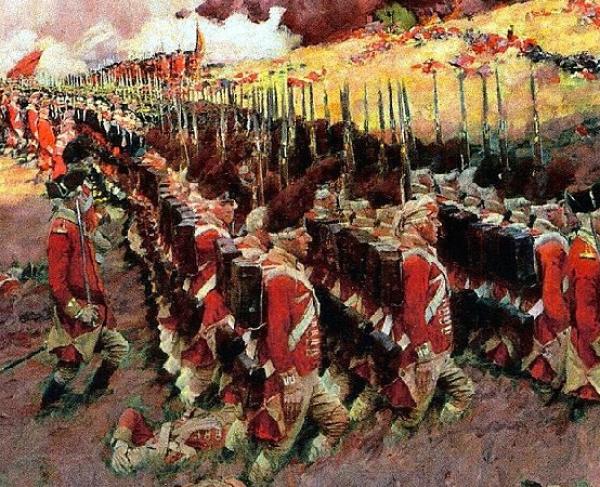

The opening gambit came on August 22, 1776. Covered by the guns of five men-of-war, 15,000 British and Hessian soldiers made an amphibious landing at Gravesend Bay on the southwestern shore of Long Island. The plan, conceived by General Henry Clinton, was to split the army into three divisions. Two divisions would make feints directly against the Americans entrenched on the wooded hills of the Heights of Guana (in the area of Greenwood Cemetery and Prospect Park today). The largest division, 10,000 men personally under the command of General Clinton, would take an unguarded pass on the left of the American line and turn the flank by surprise.

When battle was joined on August 27, the plan worked perfectly. The British smashed through American positions, sending the mostly raw troops fleeing for their lives. Washington watched helplessly from Brooklyn Heights as a regiment of Marylanders sacrificed themselves in repeated charges to buy time for the routed army to escape, lamenting, “What brave fellows must I lose this day!” With their backs to the East River, and an eager foe in front of them, Washington felt his troops were saved from total destruction by a stroke of “Providence” — a well-timed fog and a favorable wind over the night of August 29 covered an evacuation by boat to Manhattan.

Howe failed to pursue Washington, and for more than two weeks the armies remained separated by the East River. During this lull, Benjamin Franklin, John Adams and Edward Rutledge attended a peace conference convened on September 11 at the home of a Staten Island loyalist. However, as the British demanded that the Americans acknowledge the supremacy of Parliament, and not Congress, before any negotiations would begin, the talks quickly broke down.

Washington, meanwhile, had his strategy. On September 12, a council of war decided to abandon New York City and move the main army to the Harlem heights. Three days later, General Howe renewed the offensive, continuing the British island-hopping campaign by landing 4,000 troops at Kip’s Bay on Manhattan. American resistance melted before Washington’s eyes. Where before he mourned the loss of his brave men lost at Brooklyn, the general now raged, “Good God! Have I got such troops as these?"

As their pursuit continued the next day, British buglers sounded their horns in “the manner of a fox chase.” Stung by the insult, a small American force was able to drive back a detachment of British light infantry at the Battle of Harlem Heights, scoring a brief but sorely needed boost of morale.

The British suffered another setback on September 21, when a fire engulfed Manhattan, consuming nearly a quarter of the city from Bowling Green to St. Paul’s Chapel near modern-day City Hall Park. More than 1,000 structures were destroyed, including the tallest building in the city, Trinity Church.

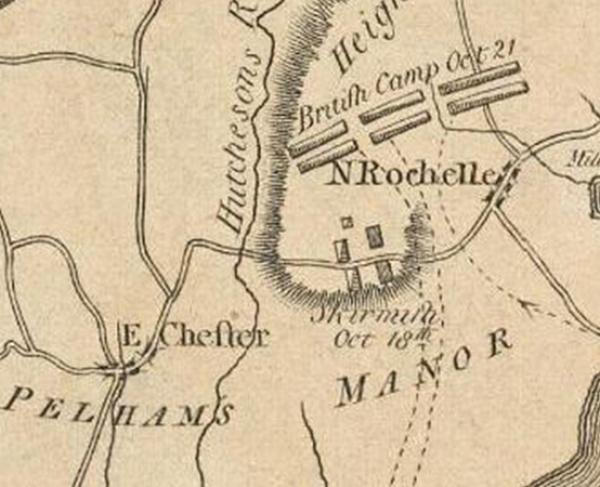

Through October, the British sought to maneuver around the American lines, landing at Throg’s Neck and again at Pell’s Point in Westchester County. Despite a desperate defense at White Plains, the Continental army had been effectively expelled from New York by the end of October.

A single American position on Manhattan Island remained — Fort Washington, built directly opposite Fort Lee to stop British shipping from sailing up the Hudson. General Nathanael Greene had convinced a skeptical Washington that the post could be held, but determined assaults up the rocky height proved otherwise. The 2,800 men killed, wounded and captured on November 16 were a loss the Continental army could ill afford.

Washington, now in New Jersey, having crossed the Hudson to join Greene’s command at Fort Lee, wept as he watched the garrison fall. But he had little time to mourn — he now had to prepare to stop any British advance into New Jersey, toward Philadelphia. Success in the coming weeks would mean victory or death for Washington, and the Revolution.

Related Battles

155

458