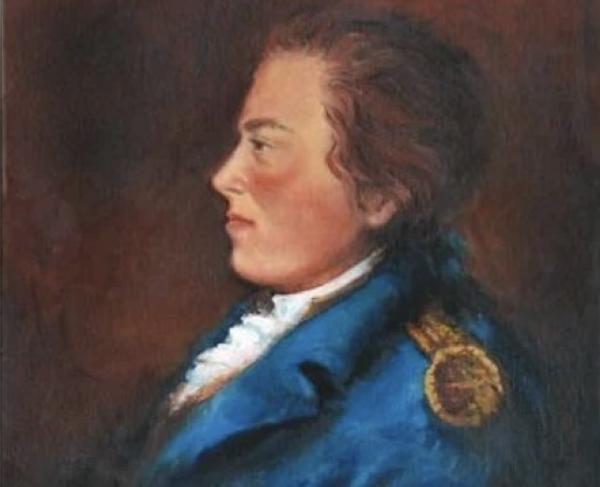

William Howe

A talented and experienced soldier from a family that produced many talented and experienced soldiers, William Howe nonetheless became the scapegoat for the British failure to crush the American Revolution early on. In spite of several crushing victories over General George Washington on the battlefield, Howe’s inability to capture him or completely destroy the Continental Army as a fighting force ultimately led to France’s entry into the war and Britain’s ultimate defeat.

From his very first moments, Howe lived his life amongst the upper crust of British society. Born in 1729 in Nottinghamshire, Howe’s father, grandfather, great-grandfather, and great-great-grandfather had all represented their town in the House of Commons, eventually earning the title of viscount in the Irish Peerage. On top of that, Howe’s mother was the daughter of Sophia von Kielmannsegg, an illegitimate half-sister of King George I himself. It is fairly surprising, therefore, that very little material exists on the Howe’s personal life, particularly his childhood and education. We know that his father, Emmanuel, died while serving as Governor of Barbados when William was five and we know that his mother, Charlotte as a relative of the Royal Family, was a frequent sight at court, and Lady of the Bedchamber to Princess Augusta, mother of King George III. We also know that he attended the prestigious Eton school, but did not go on to University, and we have very little data about his aptitude as a student. Almost everything else is unknowable. With a blue-blooded pedigree like his, though, it is no surprise that Howe and his three brothers enjoyed an easy path to success in life regardless. His eldest brother, George, joined the army, while the other two chose maritime careers. Richard joined the navy and eventually rose to the rank of Admiral of the Fleet, whereas Thomas worked for the East India Company and became a noted explorer. After leaving Eton at seventeen, William decided to follow George into the army, and purchased a commission as a dragoon officer in time for the War of Austrian succession, serving mainly in Flanders.

Howe’s next military experience was also the first that brought him to North America. Following the disastrous Braddock Expedition of 1755, the British military returned with a vengeance two years later with the goal of conquering no less than all of French Canada. Howe performed well during the Conquest of Canada, commanding a light infantry unit at the Battle of the Plains of Abraham outside Quebec City, but he suffered several personal tragedies along the way. His eldest brother and head of the family, General George Howe, died in an ill-fated assault on Fort Carillion (renamed Fort Ticonderoga), and General James Wolfe, a close friend of William’s since the Austrian War, also fell in battle in the effort to take Quebec. Still, the campaign was a rousing success, and left Howe with a firm grasp on effectively commanding troops on North American terrain.

Howe’s proven skills on the battlefield allowed him to rise to the rank of General by the war’s end, and between signing of the peace treaty and the firing of the first shot at Lexington, he spent his time developing new training manuals for the army as well as arguing for fairer treatment of the American colonies as a Member of Parliament. Whatever sympathies he had for the Patriot cause did not affect his sense of duty, however, and he arrived once again in North America with Generals Henry Clinton and John Burgoyne to relieve the besieged city of Boston and put down the rebellion. His first action in the war was at Bunker Hill, where he personally led no less than three assaults at the entrenched colonials. He demonstrated much personal courage during the battle, but still faced heavy criticism, much of which Howe agreed with, for removing the rebels from the Charlestown Peninsula at so great a cost.

Despite the heavy casualties at Bunker Hill, Gage granted Howe command over all British troops in North America on October 11th, 1775. He managed to hold the city for a few more months, until George Washington’s artillery chief Henry Knox managed to fortify Dorchester Heights with a battery on March 4th, 1776. Howe saw that the situation had become untenable and made the decision to abandon the city and retreat to Canada, but he wasted no time in striking back. With the arrival of fresh British and Hessian reinforcements, Howe took the initiative to move against New York City in coordination with his admiral brother Richard. Setting out from Halifax in late June and reaching Long Island by July, Howe attempted to open negotiations with Washington, offering pardons in exchange for an end to the insurrection. Washington refused, and confronted Howe’s invasion force in late August right where Prospect Park in Brooklyn lies today. Howe engaged, outflanked and smashed Washington at the Battle of Long Island, inflicting over 2,000 casualties and putting Washington on the run. Over the next few months, Howe slowly but surely drove the Patriot commander out of New York and into New Jersey while the Continental Army slowly disintegrated from repeated losses and desertion. For this victory, Howe received a knighthood in the Order of the Bath as New York City became the new British headquarters and remained in their hands for the rest of the war.

As Washington evacuated New York, the winter months that traditionally brought an end to the campaigning season had arrived, and while in pursuit Howe must have hoped that the dreadful conditions could permanently sink what was left of the Patriots’ low spirits. How surprised he must have been, then, to learn that Washington managed to ambush the Hessian garrison he had placed at Trenton, New Jersey the day after Christmas, only to evade capture and assault his rearguard under General Charles Cornwallis at Princeton a few days later. Despite his overwhelming victories, Howe had not taken Washington out of the fight just yet.

Nevertheless, Howe still believed he could score a swift, decisive victory over the rebels, should he find and take the proper target. And so he set his sights on the de facto capital the rebellion: Philadelphia. After wintering in New York, Howe and his army set out and landed in Head-of-Elk, Maryland and marched north to Pennsylvania. Outside the city, Howe encountered Washington’s renewed Continental Army once more at the Battle of Brandywine on September 11th, 1777. This was the single largest engagement of troops on North American soil for the entire war, with over thirty thousand troops involved, and once more, Howe exploited a critical flaw in Washington’s troop deployment, giving him the chance to outflank and drive the enemy from the field. His victory appeared to be so complete that two weeks later, Howe and his army entered and occupied Philadelphia without a fight, then defeated Washington once more at Germantown in October, but despite this string of victories, Howe’s strategy laid the foundation for Britain’s ultimate defeat. While Howe remained focused with the capture of Philadelphia, fellow British General John Burgoyne had hoped for his support in cutting off the northern colonies from their neighbors by capturing the Hudson River Valley. Abandoned by Howe, Burgoyne soon met total defeat at the hands of Horatio Gates and Benedict Arnold at Saratoga, which convinced France to enter the war on America’s behalf. Meanwhile, Howe seemed more than willing to winter in Philadelphia, fraternizing the city’s high society, while leaving Washington to his devices in Valley Forge. The home he used as his headquarters and residence, in a twist of irony, later became the homes of George Washington and John Adams during their presidencies decades later. His extended stay in Philadelphia earned him the ire of a few of his potential allies, however, including American loyalist and former delegate to Continental Congress Joseph Galloway, who later testified to Parliament that the general had passed up several golden opportunities to destroy Washington’s army and capture him. By the time Howe received word of approval for his resignation and evacuated the city in March, he had failed to accomplish any of his strategic aims: Washington and his army remained unbroken and Continental Congress did not disperse but quickly relocated to nearby Lancaster. Upon returning to New York, Howe relinquished command of North America to Sir Henry Clinton and made the trip back home to England. Despite some participation in the later French Revolutionary Wars, Howe never saw action again and served in various bureaucratic functions instead. He passed away, childless despite a long marriage to a woman named Frances Connelly, in 1814.