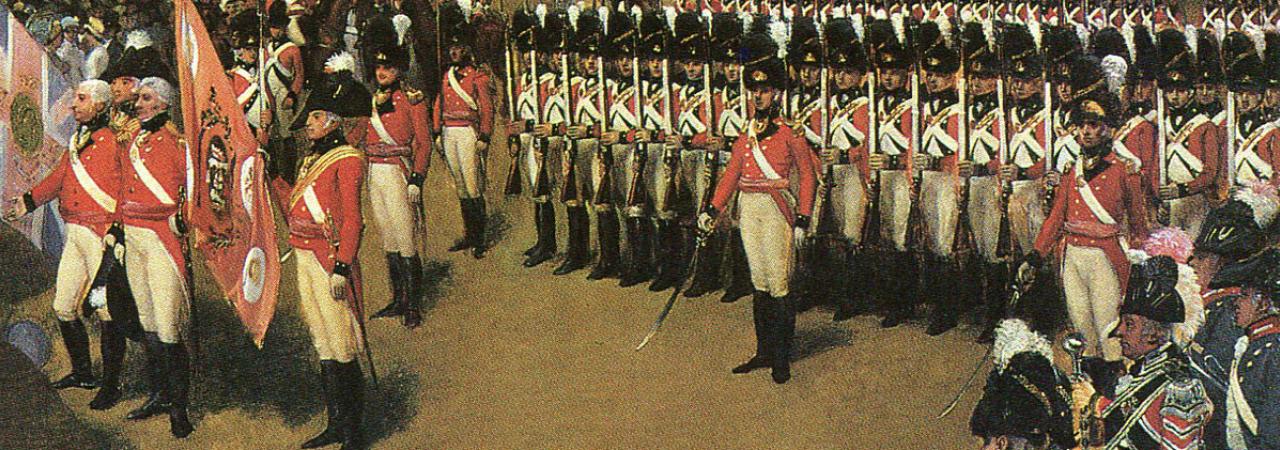

Presentation of the Colours to the Bank of England Volunteer Corps by Thomas Stothard, 1799

In the Revolutionary War, one of the distinguishing features of the British army was its discipline, the means by which British officers kept their soldiers in line. American colonists mocked the redcoats as “bloody backs,” in reference to the floggings that officers frequently used as punishment. While the idea of the British army as a collection of men forced into obedience by the threat of violence has been exaggerated over time—British soldiers were volunteers, motivated mainly by patriotism and martial pride—discipline was, as George Washington himself wrote, “the soul of an army.”

British discipline was governed by the Articles of War, a collection of over one hundred regulations that set the expectations of enlisted men and officers, and prescribed penalties for various offenses. The legislative authority behind the Articles of War came from the Mutiny Acts, an annual law passed by Parliament which gave the monarch and their government the power to form and regulate a standing army. The articles that had the most relevance to the common soldier, like the ones concerning desertion and mutiny (a term used to cover any failure to obey orders), were regularly read out loud to soldiers.

It is difficult to put together a complete picture of discipline in the British army during the Revolutionary War, because few of the records still exist. The majority of disciplinary decisions in the British ranks were made by courts martial at the regimental level. Unfortunately, few records survive from these regimental courts. Based on the records that have survived, regimental courts handed down sentences that included stopping a soldier’s pay, assigning additional physical labor (called fatigue duty), and confinement, whether in barracks or a military prison. Corporals were most commonly punished by being demoted back down to common soldiers.

The most common punishment, however, was the lash. Surviving records from four regiments during the Revolutionary War show that around ten percent of all the soldiers in those four regiments were lashed during a four-year period. A regimental court might sentence a soldier to receive between twenty-five and five hundred lashes, inflicted with a “cat o' nine tails,” a whip with nine tails. These floggings were done publicly, to set an example for the rest of the soldiers. The regimental drummers were responsible for lashing the convicted soldier. The regiment’s surgeon would observe the punishment and had the authority to halt the lashing if he believed the convicted soldier would not survive further punishment. Soldiers who were sentenced to hundreds of lashes might endure multiple sessions, separated by time to recover.

More complete records were kept for general courts-martial, which were convened to deliberate on major crimes, including those that carried a possible penalty of death. General courts-martial often handed down heavier sentences: during the Revolutionary War, the average number of lashes prescribed by general courts-martial was almost eight hundred, and more than half of all lashing sentences handed down by these courts were for over one thousand lashes. The most common crimes tried by a general court-martial were desertion (over thirty percent of all sentences), followed by robbery and murder. More than half of murder cases ended in acquittals. Murder was a capital crime, punishable by execution, but there no distinction for manslaughter, so courts were reluctant to convict in cases where the death was accidental or unintentional.

More than half of all death sentences handed down by general courts-martial were for desertion. Deserters generally were presumed guilty unless they could prove their innocence. During the Philadelphia campaign in 1777, General Sir William Howe, commander of the British forces, issued an order that any man found straggling away from the army was to be executed without trial.

Robbery, or plundering, was a major problem for British strategy. This promise of fair treatment and protection in exchange for loyalty was undermined when British and Hessian soldiers looted private homes and farms without discrimination. In December 1775, while British troops were besieged in Boston, the British commander warned that the first soldier found in the act of plundering would be hanged “without waiting for further proof by trial.” Such warnings of harsh punishment for looting were a constant feature of British campaigns: the next year, after landing on Long Island, the British commander warned that there would be “no mercy to any man found Guilty of Marauding.”

However, not every trial resulted in a guilty verdict. Around one-fifth of all general courts-martial ended in acquittal, and even guilty sentences were usually pardoned, either in part or fully, if they came with a recommendation of mercy. However, there were two distinct systems of justice: one for common soldiers and one for officers. Officers were rarely tried for obvious crimes like desertion or plunder. Instead, officer trials usually reflected politicking and infighting among the officer corps, with the most common charge being “conduct unbecoming an officer and a gentleman,” which was much vaguer and more difficult to prove. During the Revolutionary War, only three officers were sentenced to death: an ensign and captain were convicted of forgery in 1777, but their sentences were pardoned. The only officer sentenced to death and actually executed was Major Richard Stockton, who was convicted of murder.

While the ferocious discipline of the British army is often contrasted in the public imagination with the patriotic volunteer spirit of the Americans, the Continental Army had a very similar system of justice. George Washington was especially insistent that Congress give him the authority to hand down harsher sentences. By 1776 American soldiers were being sentenced to hundreds of lashes, just like their redcoat counterparts.