A Quick View From London: What the British Population Saw & Thought of the American Revolution

From our standpoint of looking back at the American Revolution, we might assume that most Americans were in favor of the War For Independence. In reality, the numbers are far smaller than most realize. John Adams famously said that about one-third of the continent was for the war, one-third was against it, and one-third was indifferent. While we cannot be sure of these estimates, consider that only about 2% of the population served in the Continental Army. Many Americans wanted economic stability, something the war did not bring. Others found the entire affair treasonous and thought the rebels had gone too far. This latter sentiment, felt by continental Americans, was the primary belief among most of native mainland citizens in Great Britain. Yet when the war showed signs of failure, the British population began questioning its government and the necessity of battling for a territory that was distant and unruly.

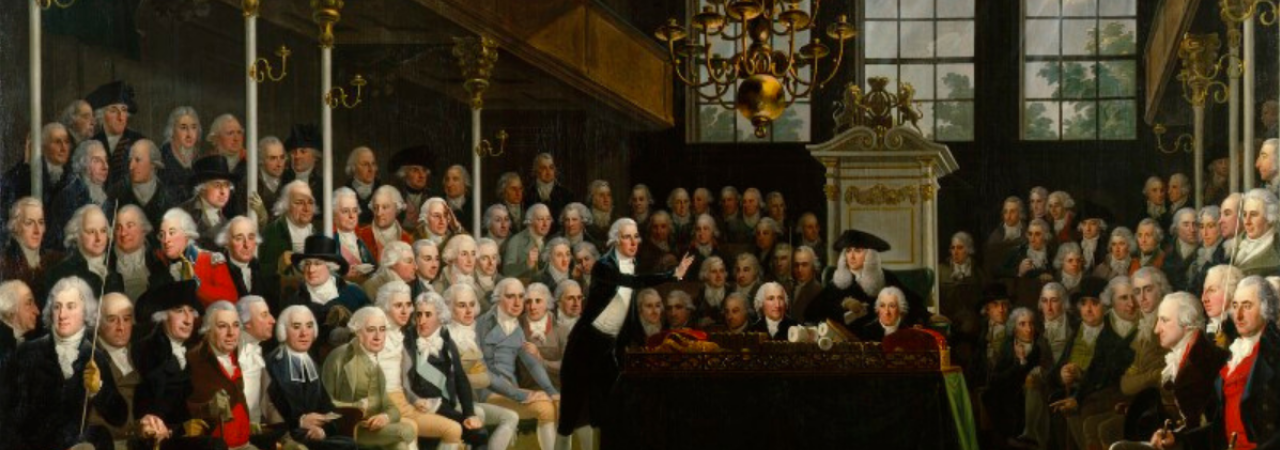

Early pamphlets openly mocked and harassed American concepts of liberty and freedom. For Londoners, laws and rights under the English Constitution already established such privileges, and because Britain was at the time the most powerful nation in the world, the idea of being oppressed by Parliament seemed outrageous. To their disadvantage, mainland citizens viewed Americans as backwoods cousins; British subjects but inferior. Colonists were considered second-class citizens whose purpose was to provide wealth, trade and stability for the greater British Empire. The general belief was that Americans owed something for their allegiance. These views metastasized among the wealthy aristocratic land gentry who made up the House of Lords. Their counterparts in the House of Commons also were of the belief that the Americans owed something for their allegiance and the protection the British government provided them, but even these prejudices began to wane as news from North America changed during the war. Newspapers carried the latest reports from America, and despite arriving sometimes months after events occurred, it nevertheless affected how mainland British citizens felt about the war. Before the events of 1775-76, the majority of citizens objected to American hostilities and were supportive of efforts to put down the insurrection. This was reinforced by reassurances by Lord North’s ministry that any rebellion would be squashed quickly, and the agitators would be brought to justice.

What the British government, and the people, failed to recognize was just how difficult it would be to police and subdue an entire continent with a foreign force. The logistics of supplying that force from across an ocean added to the problems that became apparent soon enough. As early British victories gave way to events like Trenton in 1776 and then Saratoga in 1777, drawing France into the war with it, public opinion began to change. Whereas the voices opposing war were mainly found in the merchant class at the war’s outset, the continued bleeding of resources were now effecting prices within British society. These sentiments became stoked by a growing number of MP’s in Parliament who objected to the execution of the war. Perhaps no other member of Parliament held sway like Edmund Burke, the radical conservative who championed American complaints of taxation and representation. In his first years in Parliament, Burke emerged as a defendant of American interests, though he was steadfastly against separation and the war’s motives. Believing Parliament had badly miscalculated the mood of British America and only inflamed the situation by pressing more tax measures, Burke became the voice of the anti-war movement within Parliament. Along with a handful of other MP’s, including Charles James Fox and William Pitt the Younger, this became the counterweight to Lord North’s ministry and that of the king’s continued insistence of war with America. And as the British strategy for winning the war, put together by George Germain, showed no clear objectives for removing the Continental Army or the rebellion’s leadership, the king’s stance became a refusal to see the reality of the situation. Capturing colonial cities like New York, Philadelphia and Charleston had not produced the promised victory, or a capitulation of the rebel Congress. By 1781, much of the British public was now against the war. And when news arrived of Cornwallis’s defeat at Yorktown, North knew his tenure in the government was over, and the fight for suppressing the rebellion was likely lost for good. After North’s resignation, the king remained committed to retaining allegiance from America, albeit allowing many of their grievances to be addressed. As he later claimed, he was the last to accept American independence.

The consequences of the American Revolution rippled through Europe, and for the first time in modern history, a new nation emerged that did not owe allegiance to a monarchial government. When Washington resigned command of the Continental Army at the end of 1783, the motion of giving up power was so radical that a defeated King George III remarked, “if true, he is the greatest character of the age.” Beyond the reverberations of liberty and self-government, the United States threatened the ancient regime of top-down rulership embedded in European culture. By decade’s end, France would be in the midst of its own revolution to dispose of monarchial rule, though the French Revolution largely failed because its proponents did not hold the same ideals as their American counterparts.

For many within London, there was a two-fold situation as the 1780s progressed. Britain had secured favorable trading rights with the United States, ensuring a growing market of trans-Atlantic consumerism. There also remained a largely English-bent on American culture with a common language assisting a continuing partnership. But ministers also looked for opportunities to undermine the United States. Several plots moved behind the scenes to instigate unrest as Americans continued to push westward. Native American groups remained skeptical of American intentions, and welcomed British delegates, who were trusted from decades of mutual friendship. London further undermined American interests by retaining their forts on the outskirts of the Mississippi River Valley. Though the Treaty of Paris secured the removal of all British military outposts from the Great Lakes region, the army stubbornly remained after the war to offset the frustration held by many loyalist Americans who’d yet to receive compensation for lost assets and property from the war. Adding to this, the British Navy regularly harassed American merchant ships on the high seas, a practice that would escalate into the 1790s as Britain and France faced off once again. In short, while the king accepted American independence (as he bluntly told John Adams in person in 1785), the British government looked for opportunities to strike where it could potentially damage the infantile United States. Success of the new country was not a forgone conclusion, and London would have enjoyed nothing more than seeing it crumble and potentially fall right back into its grasp.

Further Reading:

- Europe in the Eighteenth Century 1713-1783 by M.S. Anderson

- The Long Fuse: How England Lost the American Colonies, 1760-1785 by Don Cook

- London Life in the Eighteenth Century by M. Dorothy George

- Rope of Sand by Michael G. Kammen

- King George III and the Politicians by Richard Pares