A Tale of Two Pitts: The Careers of the Elder and Younger William Pitt

On January 23rd, 1806, Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger passed away in his London home, his final words being, on account of Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte’s crushing victory over coalition forces the prior month, “Oh my country! How I leave my country!” With him died a political dynasty that dominated British politics for much of the latter half of the 18th century and in many ways helped make Britain the imperial power it soon became after his demise. In this article, we shall look at how father and son, both named William Pitt, navigated their careers through the three greatest political crises of their day, the Seven Years War, the American War for Independence, and the French Revolution, and how their decisions while in power impacted political culture in Britain as well as Britain’s standing upon the global stage.

Our story first begins with the rise to prominence of William Pitt the Elder, born in 1708 to a well-to-do mercantile family with a long history of success in politics both in Parliament and the Colonies. Like many men of his class, he attended the prestigious Eton School as a boy and afterward moved on to study at first Trinity College, Oxford then Utrecht University in the Netherlands. How long he studied and whether he earned his degree is unknown, historians have suspected that he first encountered there the works of Dutch lawyer and political theorist Hugo Grotius, whose on the importance of freedom on the high seas for international trade, proved highly influential on Pitt and useful throughout his political career. After university, Pitt joined the army only to see no action, but he did manage to form a close relationship with his commanding officer, Richard Temple, 1st Viscount Cobham. So, in 1734 and with the help of his elder brother, Thomas, Pitt followed his mentor into Parliament, “representing” the uninhabited town of Old Sarum (this sort of arrangement where a Member of Parliament stood for a seat without any constituents, and thus entered the House of Commons unelected, was called a “Rotten Borough.”)

As an MP, Pitt soon fell into a faction within the larger Whig Party commonly referred to as “Cobham's Cubs” that stood in opposition to Robert Walpole, the de facto first British Prime Minister, as well as King George II himself. From Pitt’s point of view, Walpole and the King were far too willing to negotiate with the European powers at the expense of the rights of British citizens and the freedom of British trade on the high seas, and that they were too focused on the King’s personal interests in the German principality of Hanover, which the German-born King ruled separately from Britain. One might think that earning the ire of the prime minister and the King would make for a brief career in politics, but Pitt’s remarkable talent for speechcraft and rhetoric found him many friends in Parliament, “Patriots” as they dubbed themselves, and his fervent support British national interests made him wildly popular with the wider public who later dubbed him “The Great Commoner” for his refusal to accept a noble title. One of Pitt’s admirers included no less than the King’s own son Frederick, the Prince of Wales. With this wide array of support, Pitt found more than enough support for advancement after Walpole’s administration collapsed when his appeasement policies failed to keep Britain out of the War for Austrian Succession in 1746. The new government, led by Pelham brothers Henry and Thomas, 1st Duke of Newcastle, wanted to include Pitt as Paymaster of the Armed Forces, much to King George’s chagrin. Though the period between 1748 and 1754 was mostly peaceful, Pitt still made his voice heard in several prominent political disputes, often with his own government. He vigorously opposed an attempted by Newcastle to downsize the Royal Navy from 10,000 personnel to just 8,000, and successfully convinced the House of Commons to reject the bill. Pitt also voiced support for a 1753 bill that aimed to naturalize Jewish residents in Britain as citizens which were defeated a year later after sparking a wave of anti-semitism, but both of these acts reflect the main principles upon which Pitt simultaneously based his political career: his support for the navy as the glue that held the British Empire together and his concern for the rights of those that dwelt within it.

Pitt’s true rise to power, however, came with the onset of yet another conflict with Britain’s longtime geopolitical rival, France. As the conflict that became the Seven Years War rapidly spread from a Virginia militia colonel’s minor skirmish on the North American frontier to a truly global war, several military disasters such as the 1756 Fall of Minorca, and important Mediterranean naval base to French forces caused chaos in London as Parliament panicked on how to respond to the crisis, and the constant squabbling between Pitt, the King and several other ministers crippled Britain’s ability to form a stable government. The situation only rectified itself in 1757 when Newcastle offered to bring Pitt into a new ministry officially as Secretary of State for the Southern Department, overseeing foreign relations with the European Catholic and Islamic powers while also managing Britain’s colonial interests. Unofficially, however, Pitt became himself a de facto second Prime Minister, sharing power with Newcastle to direct the war effort more closely aligned with his vision. It was the kind of role Pitt was born to play.

Pitt’s strategy was simple but effective. Rather than tangle the army in Europe defending the King’s personal interests, Pitt allowed Britain’s main allies, Prussia and Portugal, to take the lead role on the Continent, instead of focusing on using Britain’s naval prowess to her full advantage. By 1759, often labeled the Anno Mirabilis, or “Year of Miracles,” the results seem to have spoken for themselves. British forces attacked economically vital yet poorly defended French colonies all over the world, from Caribbean sugar plantations to trading settlements on the West African Coast, but the greatest prizes were in North America and South Asia. Under Pitt’s direction, the British army under General Jeffrey Amherst invaded the colony of New France and took the capital city of Quebec, ending French rule over modern-day Canada, while in India, East India Company troops under Colonel Robert Clive smashed a French-supported Bengali army at Plassey, marking the start of British supremacy over the subcontinent for the next two centuries. In the words of writer Horace Walpole, “Our churchbells are worn threadbare with their ringing.” Pitt even managed to obtain a small personal miracle that year in the birth of his second son, Pitt the Younger.

Even as his efforts proved enormously successful, however, the Elder Pitt continued to butt heads with the monarchy, even as George II passed away in 1760 and his grandson, George III, took his place. In spite of Pitt’s calls for a preemptive attack on Spain before it entered the war on France’s side, the new King George aimed to end the war as swiftly as possible, installing his personal confidant the Earl of Bute to the Cabinet. Bute used his influence with the King to stymie any attempt by Pitt to push to expand the war, even as his prediction regarding Spain proved prescient, and so Pitt resigned in protest in October of 1761. He quickly returned to his previously role as “The Great Commoner” in Parliament, championing a wide variety of both Liberal and Imperial causes, protesting both the 1763 Treaty of Paris, which he believed to be too generous to France and, even more to his chagrin, and even more to his chagrin, the treatment of the American colonists by Parliament, held responsible for the war he himself had waged.

In speech after speech, the Elder Pitt railed against Parliament for what he saw as overstepping its bounds and taxing British citizens without their consent. “I have been charged with giving birth to sedition in America,” he announced to the House of Commons on January 14th, 1766. He frequently praised Americans who resisted the Stamp Act as “Defenders of the Cause of Liberty, and when the Act was repealed March of that year, Pitt found himself as popular in America as he was in Britain, and a few months later, he finally became Prime Minister in an official capacity, after several other governments had failed. Unfortunately, Pitt’s premiership proved to be just as unstable, lasting fewer than two years. He left most of the actual governance to his cabinet, which continued the policies of taxation he himself was opposed to, and many of his supporters found his decision to finally accept the title of Earl of Chatham alienating. After resigning to the House of Lords, his health increasingly deteriorating, Chatham continued to speak out for the defense of the Empire against external foes and reconciliation with the Americans simultaneously for the remainder of his life and career, even after hostilities broke out. Those two positions came to a head, of course, when France and Spain intervened in the war on America’s behalf, leading to him giving his final public speech on April 7, 1778, crying, “In God’s name, if it is absolutely necessary to declare either for peace or war, and the former cannot be preserved with honour, why is not the latter commenced without hesitation?”, before collapsing on the floor. He died a month later, mourned across the English-speaking world, including an unnamed member of the Sons of Liberty who reportedly made a toast to “Magna Charta (sic), the British Constitution, Pitt and Liberty forever!”

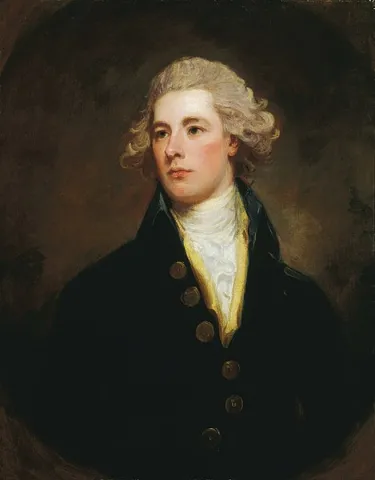

As the Elder Pitt passed, however, the Younger Pitt had just become ready to take his place, having already graduated from Cambridge University at the age of 14, and soon established himself as a respectable lawyer two years later, and followed his father’s footsteps into the House of Commons soon afterward in 1781. Thin, often sickly, aloof, and lacking much of his father’s good humor, what he did share was his patriotism, commitment to civil liberties, and talent for rhetoric. Pitt continuously called for an end to the American war following the loss at Yorktown, and after the North ministry collapsed, Pitt accepted the senior role of Chancellor of the Exchequer under the Duke of Rockingham. He soon lost that role after the rise of the Fox-North coalition, which negotiated the Treaty of Paris and finally ended the war, but Pitt himself played a role in ending that government by defeating a bill that sought to nationalize the East India Company, causing King George to dismiss the government and appoint Pitt as the new Prime Minister in its stead. At 24 years old, Pitt was the youngest, before or since, person to be named Prime Minister of Great Britain, and unlike his father, the longest-serving as well.

The Younger Pitt played are far lesser role than his father on the impact of the Revolutionary War, but in dealing with the fallout of that conflict, in fostering Britain’s post-war economy, acting against the French Revolution, fending off invasion and other threats posed by Napoleon Bonaparte, managing King George’s mental health crises, and safeguarding his father’s vision for the British Empire, Pitt continues to stand alongside his father as one of the most towering figures in British and world history.

Further Reading

- The Long Fuse: How England Lost the American Colonies 1760-1785 By: Don Cook

- William Pitt The Younger: A Biography By: William Hague

- The Life of William Pitt, Earl of Chatham V1 (1913) By: Basil Williams