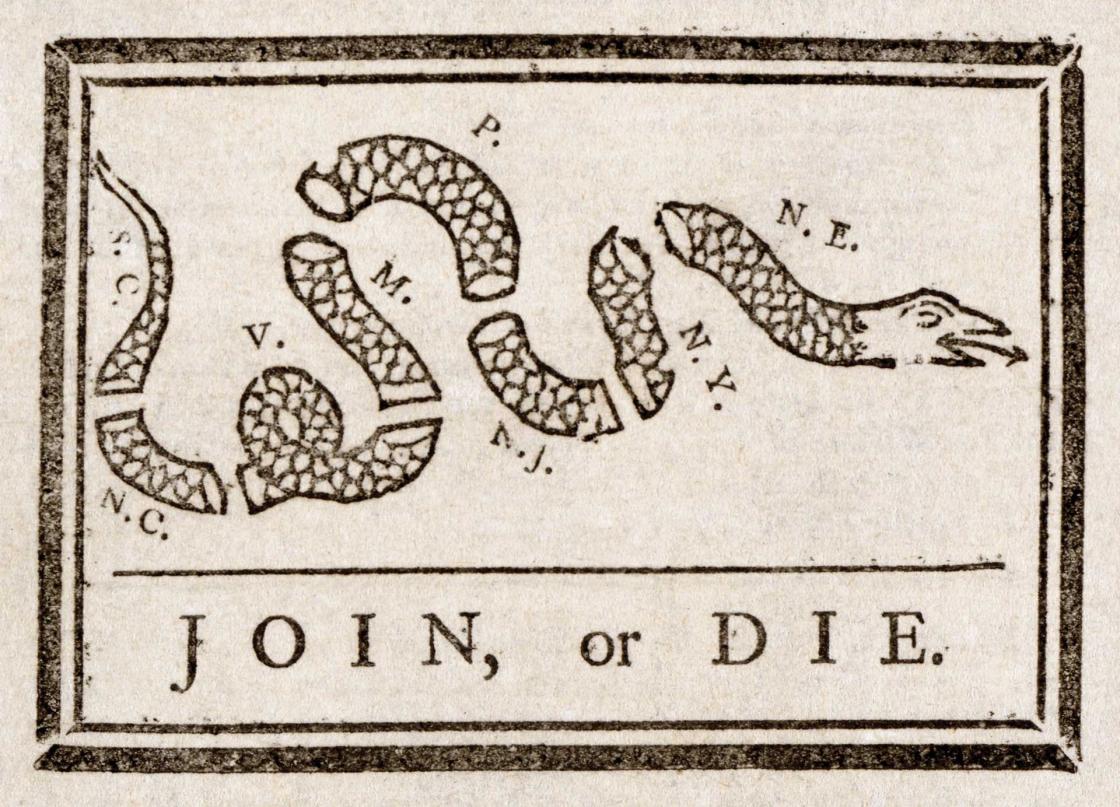

The 1754 political cartoon Join or Die by Benjamin Franklin.

The skirmish begun by George Washington and his colonial compatriots at Jumonville Glen, Pennsylvania, in 1754 was a spark that soon became a global conflagration. Long-simmering tensions between Britian and France boiled over in the Americas, Europe, West Africa, India and the Philippines. Prussia and Hanover were drawn into the fight on the side of Britian; Spain, Austria, Saxony, Sweden and Russia took up arms allied with France. When the Treaty of Paris was finally signed on February 10, 1763, the future trajectory of North America had fundamentally shifted.

Fighting in the theater of conflict known globally as the Seven Years’ War and locally as the French and Indian War (although various Native American groups took up arms on both sides), concluded with the surrender of Montreal on September 8, 1760, but it continued in Europe until late 1762, with Britain emerging triumphant. Imperialist members of Parliament did not want to yield the territories gained during the war, but another faction believed that it was necessary to return a number of France’s antebellum holdings to maintain a balance of power in Europe. This latter measure would not, however, include France’s North American territories and Spanish Florida. In the words of 19th-century historian Francis Parkman, “[H]alf the continent had changed hands at the scratch of a pen,” and France’s North American empire had vanished.

The treaty granted Britain Canada and all of France’s claims east of the Mississippi River, excepting the city of New Orleans, which France was allowed to retain. The Louisiana Territory beginning on the opposite bank was ceded to Spain, although British subjects were guaranteed free rights of navigation on the river. Spain extended Britain’s King George III’s North American empire in the form of Florida, transferred in exchange for the return of Havana and Manila. This gave Britain total control of the Atlantic Seaboard from Newfoundland all the way down to the Mississippi Delta. Further, the conquered Caribbean islands of Saint Vincent, Dominica, Tobago, Grenada and the Grenadines remained in British hands.

The loss of Canada, economically, did not greatly harm France. It had proved to be a money hole that cost the country more to maintain than it actually returned in profit. The sugar islands in the West Indies were much more lucrative, and to France’s pleasure, Britain returned Martinique and Guadeloupe. Although His Most Christian Majesty King Louis XV’s influence in North America had receded, France did retain a tiny foothold in Newfoundland for fishing rights.

The inhabitants of the British colonies in North America were jubilant upon hearing the results of the Treaty of Paris. For nearly a century, they had lived in fear of the French colonists and their Native American allies to the north and west. Now France’s influence on the continent had been nearly extinguished, and they could hope to live out their lives in peace and autonomy without relying on Britain’s protection.

But the war’s aftermath drove a profound wedge between Britain and her colonists. The global conflict had ballooned Britain’s national debt nearly twofold, and the colonies were asked to shoulder a good portion of the burden of paying it off via taxes imposed on necessities that the colonists considered part of everyday life. Proud English folk, the colonists viewed themselves as partners in the British Empire, not subjects of it. King George III did not see it this way.

Another major point of contention was the land west of the Appalachian Mountains, which had been heavily fought over during the war. Many in the British military and the colonies viewed “conquered” land as His Majesty’s dominion. To them, the territory west of the Appalachians was not shared or Native land — it was rightfully open for British trade and settlement. Disputes soon erupted with the Native Americans, who had previously allied with the French, inhabiting the region.

What transpired next has gone down in history as Pontiac’s Rebellion (1763–1764), after a regionally powerful Odawa war chief, and involved members of the Seneca, Ottawa, Huron, Delaware and Miami tribes. Various uprisings and uncoordinated attacks against British forts, outposts and settlements in the Ohio River Valley and along the Great Lakes ravaged the frontier. Although a handful of forts fell, two key strongholds, Forts Detroit and Pitt, did not capitulate. In an attempt to quell the rebellion against British authority, the Royal Proclamation of 1763 was issued. The French settlements north of New York and New England were consolidated into the colony of Quebec, and Florida was divided into two separate colonies. Any land that did not fall within the boundaries of these colonies, which would be governed by English Law, was granted to the Native Americans.

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 further alienated the British colonists. Many sought to settle the west, and Pennsylvania and Virginia had even already claimed lands in the region. The proclamation prohibited the colonies from further issuing any grants. Only representatives of the Crown could negotiate land purchases with the Native Americans. Just as France had boxed the colonies into a stretch along the East Coast, now George III was doing the same.

The French and Indian War had initially been a major success for the 13 British North American colonies, but its consequences soured the victory. Acrimony over taxes imposed to pay war debt, constant struggle with Native Americans over borders and territories and the prohibition of expansion to the west fueled an ever-increasing “American” identity as the colonists — already 3,000 miles away from Britain — grew philosophically and emotionally further apart from the mother country.