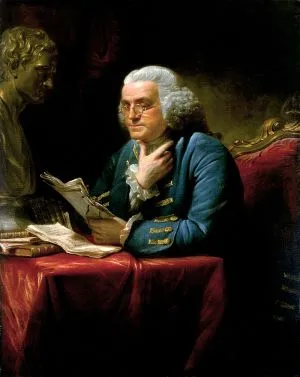

In 1766, Philadelphia printer Benjamin Franklin answered a summons to a hearing by the House of Commons in London. The purpose of the hearing was a public examination, through which Franklin hoped to advise Parliament on how to resolve the outrage in the North American colonies over a series of taxes levied on them by London. Franklin, at this time, was a strong believer in the idea of a British Empire “Upon which the sun never set, whose bounds nature has not ascertained” as the aristocrat George Macartney put it, and he had spent much of his time in Britain ingratiating himself to London high society, where he proved wildly popular. And yet, Franklin always considered himself at least partly American, and though he hoped the motherland and the colonies could avoid conflict, he resolutely defended the American’s outrage throughout the hearing. Franklin’s examination contained many sticking points, despite his conciliatory tone, but he quickly and bluntly pushes back against the notion that the colonists benefit from British protection while sacrificing nothing of their own, especially in the recent war. He argues, “That is not the case. The Colonies raised, cloathed (sic), and paid, during the last war, 25,000 men and spent many millions,” and this debate, over who should bear the consequences of this previous global war, is probably the main cause of the ultimate break between America and Britain, and even dictated how the sides were drawn when the conflict became global yet again.

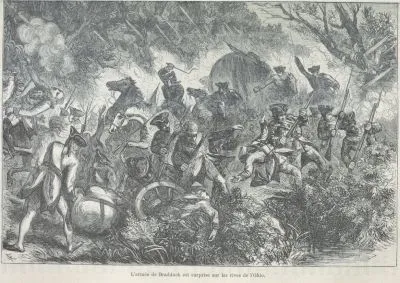

At the time of its conclusion, the Seven Years War, which really went on for nine, was among the largest and wide-ranging conflicts the world had yet seen, with well over a million casualties across the world. Battles raged on land and sea across the globe, from Europe to the Caribbean and from the African Coast to the Indian Subcontinent. The war began however in North America, where a series of conflicts on the frontier between the British colonies and New France (involving a certain militia colonel George Washington) provided the spark that lit the fire across the rest of the world. This is why in America the war is generally called the “French and Indian War,” since the sparsely populated colonists of New France depended heavily on Native American allies to provide necessary manpower. Despite some early setbacks, however, the war went spectacularly well for the British. Using their Prussian and Portuguese allies keep France and Spain occupied in Europe, Great Britain used its naval superiority to full advantage in supporting the North American and Indian fronts. As a result, Britain effectively conquered France’s holdings in India, and more importantly to this topic, all New France, the lands of modern Quebec, Ontario and the American Midwest.

This success came with a cost, however, since like most of the great European powers that participated, Britain had nearly bankrupted itself—with the British debt exceeding £140 million by the cessation of hostilities. Maintaining the expansive new territories won in the war only added to the expenditures. The Americans saw the new lands as a grand opportunity to expand and settle, but of course, the territory already was, by around 80,000 French Canadians and many Native American groups, all of whom were now technically British subjects and few of whom took the news lightly. Parliament needed to find someway to cover the costs of the conflict. The American colonies, which had previously been governed with a light touch, ignoring what few regulations London did place on the colony half the time, and where the war had essentially begun, looked like a useful source of extra revenue.

The immediate repercussions of the war, however, was the explosion of further conflict on the Northwest frontier with Pontiac’s War, sometimes called Pontiac’s Rebellion. It could be argued that the fighting was actually a continuation of the French and Indian War, as many of the belligerent tribes, which included several coalitions of Algonquin and Iroquoian-speaking peoples, were aggrieved at the stricter regulations on trade and gift-giving set by the British, specifically General Jeffrey Amherst, compared to the more conciliatory policies of the French. Many also worried about increased European settlement, which as stated before, was a desire the Americans made no secret of. The fighting lasted around three years and took on an exceptionally brutal nature at points, but it did end up resolving peacefully. But part of the resolution involved strict enforcement of the 1763 Proclamation, forbidding settlement west of the Appalachian Mountains, keeping the peace on the frontier, but infuriating the colonists that hoped to find their fortunes out west.

These outrages continued as the British Parliament actually began levying taxes upon the colonies. Beginning with the Stamp Act of 1765, which proved immediately unpopular with the colonists, they followed up their plans to raise revenue by taxing tea, sugar as well as cracking down on the smuggling they frequently used to get around. As the taxes continued, so to did colonial resistance, who slowly but surely began referring to themselves as “Patriots” and began advocating for more radical positions than the restoring of their English liberties. The increasingly partisan political climate turned even Ben Franklin into an advocate of total Independence from Great Britain Events such as the Boston Massacre and Boston Tea Party provoked crackdowns from Parliament as well, which included the quartering of British soldiers in American private homes and the complete closure of the port of Boston, continuing the cycle. Things came to a head on April 17th, 1775, when Patriot militias and British regulars fired upon each other at the Massachusetts town of Lexington.

The impact of the Seven Years War did not end with the outbreak of the Revolutionary War, of course. It also greatly impacted how and where the war was fought. Patriot military strategy relied heavily on soliciting Britain’s old foes, France and Spain, too willing to take back lost ground against Britain, as allies in their own struggle. Their combined ability to expand what was once a regional conflict to a global war in the Mediterranean, Caribbean and Indian Ocean greatly reduced Britain’s ability to project it’s full military power onto North America, saving the cause of Independence from what could have been a swift and gristly end.