On October 19, 1781, General Lord Charles Cornwallis surrendered 7,000 British soldiers to the Continental Army after a crushing defeat at the Battle of Yorktown. When news of Lord Cornwallis’s surrender reached Great Britain, Prime Minister Lord Frederick North, the 2nd Earl of Guilford seized “as he would have taken a ball in his breast” and exclaimed “Oh, God! It is all over!” At that moment Lord North, along with the rest of Parliament and King George III, realized that victory over the Thirteen Colonies was not inevitable. In actuality, victory required significantly more troops, more resources, and more money than Parliament could give to the effort. Instead of sending more troops across the sea to North America, British delegates were sent to France to begin forging a peace treaty with the United States. Two years later on September 3, 1783, the Treaty of Paris was signed and the Revolutionary War officially came to an end.

Creating this peace treaty was not a quick ordeal. Since 1770, Lord North was Prime Minister of Great Britain and refused to negotiate with the British colonies in North America. Throughout his tenure, North had encouraged taxation on the colonies and their subservience to Great Britain. Once the first shots of rebellion were fired at the Battle of Lexington and Concord, Lord North issued military intervention to squash the “rebellion.” He refused to respond to the Olive Branch Petition, which was written by the First Continental Congress to broker peace between the two nations before an all-out war, and stubbornly believed in Great Britain’s victory. His steadfastness to this goal was his downfall. With the news of Lord Cornwallis’s surrender, North’s belief in Britain’s victory was shattered. To save face, he attempted to negotiate with the Thirteen Colonies with the Conciliation Plan, a plan that voided the Intolerable Acts if the Colonies resubmitted to Britain’s rule. However, these concessions came too late and the Thirteen Colonies wanted independence from Great Britain, not leniency. The Conciliation Plan was rejected. After this rejection, Parliament turned against Lord North and instigated a motion of “no confidence.” This motion led to Lord North’s resignation on March 20, 1782.

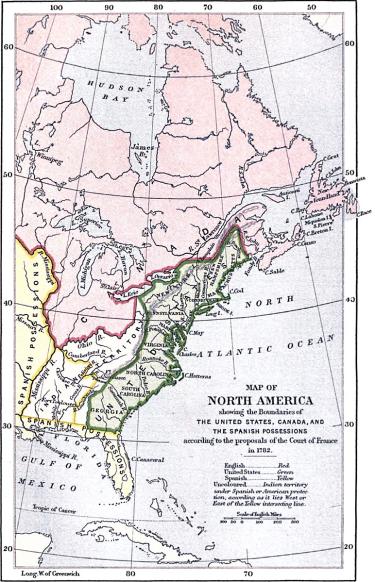

As Lord North was attempting to pass his Conciliation Plan, the United States was working with French diplomats to secure a peace treaty. France originally proposed that the peace treaty parcel North America between the fighting powers. They recommended that the continent be split so that the United States could gain the land east of the Appalachian Mountains, England could keep land north of the Ohio River, and Spain could maintain leadership of the South. West of the Appalachian Mountains was reserved for Native Americans and served as a buffer between the different nations in the New World. The American delegates were unhappy with this deal because it limited the United States’ ability to expand westward in the future. As this treaty was discussed, Lord North left office and the next Prime Minister was elected. The new Prime Minister Charles Watson-Wentworth, 2nd Marquess of Rockingham looked more favorably on accepting the United States’ Independence and negotiating with the former colonies than Lord North was. Hoping to find a more favorable treaty with this new British leadership, American delegates began working directly with Great Britain instead of with France. Unfortunately, Watson-Wentworth died fourteen weeks after his instatement. However, the subsequent Prime Minister William Petty, 1st Marquess of Lansdowne, known as Lord Shelburne, was also amicable to a British and American peace and continued the peace talks between the two countries.

Lord Shelburne considered the emerging United States as a strong economic ally with Great Britain. In the new negotiations, Great Britain allowed the United States all land east of the Mississippi River, north of Florida, and South of Canada. This proposed northern border is the same northern border that is in place today. In addition, the United States gained fishing rights off the eastern coast of Canada in exchange for helping loyalists recover property and goods that had been confiscated during the Revolutionary War. Lord Shelburne hoped that these highly favorable terms for the United States could ease tensions between the two countries and encourage future mutually beneficial deals. French Foreign Minister Charles Gravier, the Count of Vergennes, was frustrated that the United States worked directly with Great Britain as opposed to accepting the French’s proposed peace treaty. He noted that “The English buy peace rather than make it.” Once the Americans began negotiating with the British, Great Britain also began negotiations with France and Spain to ensure peace on those fronts. These peace treaties focused on trading rights, fishing rights, and the handing off of different land deeds.

The main American delegates that worked for these negotiations were Benjamin Franklin, John Jay, and John Adams. Thomas Jefferson was nominated to work on these peace treaties, but was unable to leave the United States because he was serving as Governor of Virginia. Henry Laurens was key in negotiating with the British during the later stages of the peace talks but was absent during the beginning because he was imprisoned in the Tower of London from 1780 to 1781. A year prior, he had been nominated as foreign minister to the Netherlands and had successfully negotiated their financial and military support for the war. However, on his return trip to the Netherlands after the negotiations, he was intercepted by a British ship and arrested for conspiring with the Dutch. He was the only American to be held in the Tower of London during the war. William Temple Franklin, Benjamin Franklin’s grandson, was the American delegation’s secretary during the peace talks. He is depicted in Benjamin West’s 1783 unfinished portrayal of the American and British delegates for the peace talks. After months of discussions between these men and the British delegates, the Treaty of Paris was drafted on November 30, 1782. The treaty was formally signed by the United States on Great Britain on September 3, 1783. With this signing, the American Revolutionary War officially came to an end.

Further Reading:

- The Diplomacy of the American Revolution: By Samuel Flagg Bemis

- Peace and Peacemakers: The Treaty of Paris 1783: By Ronald Hoffman and Peter J. Albert

- The Peacemakers: The Great Powers and American Independence: By Richard B. Morris

Related Battles

389

8,589