Here from the Start

Native Americans’ Complex Contributions to Military History

Shining a light on the stories of Native Americans builds a more complete understanding of our history and multifaceted national identity. From Pontiac’s Rebellion to the Navajo code talkers and beyond, our military history is imbued with native connections.

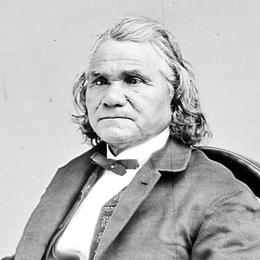

"We are all Americans."

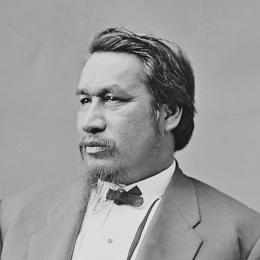

Lt. Col. Ely S. Parker (Hasanoanda or “Leading Name”): Seneca aide to Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, and scribe to the terms of surrender that ended the Civil War

The stories of Native Americans — from the colonial period through the divisive days of the Civil War — are a vital component of the history of our nation’s complicated growth. In efforts to secure the survival of their people, cultures, and homes, America’s native peoples made indelible contributions to the wars that shaped the nation we know today. Several would pick up arms and raise their voices to advance their cause, showing their unwavering strength. In fact, Native Americans have served with distinction in every major American conflict for over 200 years. There were also instances that caught unsuspecting or peace-seeking natives in the crossfire of formative conflicts, causing several to become targets of heinous war crimes.

Even as many native peoples sought “peace and friendship” — the common phrase employed within hundreds of U.S.-Indigenous treaties — they were met with broken promises that took the form of constant loss of tribal lands and an ever-growing hostility with white settlers.

The Trust is committed to elevating stories that relay the Native American experience within America’s formative conflicts through digital interpretation and continued preservation at hallowed ground where Native Americans lived, struggled and fought. The Trust has worked with tribes on numerous occasions to solicit their invaluable input as part of the Section 106 review process. The Trust’s interactions with tribes regarding historic preservation has been uniformly positive, and we look forward to further successful partnerships in the future.

Preservation Efforts

"We have neither land nor home, nor resting place that can be called our own."

John Ross (Cooweescoowe): principal chief of the Cherokee in Georgia; this line comes from an 1836 letter written by Ross and addressed to “the Senate and House of Representatives,” as he protested the fraudulent Treaty of New Echota that forced the Cherokee out of Georgia.

Saving Hallowed Ground Where Native Americans Lived, Struggled and Fought

The American Battlefield Trust has been fortunate to help facilitate the telling of native stories by preserving land with important indigenous connections. The sites vary widely, in both geography and time period.

Of the associated lands that the Trust has preserved, some of them have witnessed active Native American participation in the Civil War and other early American conflicts. Other sites were saved almost by accident: centers of ancient cultures that lived long before Europeans arrived in the New World, which just so happened to lay where battles were fought centuries after their decline. However, all have an important story to tell when it comes to Native Americans’ role in shaping the history of the land we now share. Among the sites that our work has transpired, associated lands — where Native Americans lived, struggled, and fought — include: Sand Creek (Colo.), Chickamauga (Ga.), Wood Lake (Minn.), Corinth (Miss.), Cabin Creek (Okla.), Honey Springs (Okla.), and Chattanooga (Tenn.).

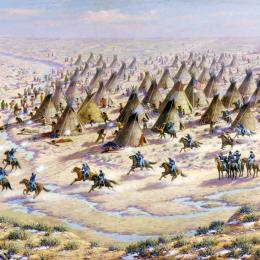

Site of one of the worst massacres of Native Americans with approximately 200 Cheyenne and Arapaho lives lost.

Where the Santee Sioux and U.S. troops fought in the last major engagement of the Dakota War of 1862.

Site of two Civil War battles — on Cherokee nation land — with Confederate forces led by general and Cherokee leader Stand Watie in both instances.

Land where the Cherokee nation settled and thrived — only to be mercilessly removed to Oklahoma on the Trail of Tears in the 1830s.

Native Perspectives

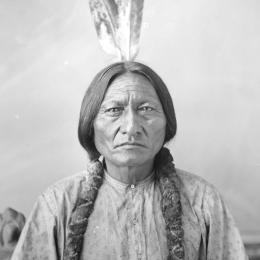

“If the Great Spirit had desired me to be a white man, he would have made me so in the first place. He put in your heart certain wishes and plans, in my heart he put other and different desires. Each man is good in his sight. It is not necessary for Eagles to be Crows. We are poor... but we are free. No white man controls our footsteps. If we must die... we die defending our rights.”

Sitting Bull: Lakota Sioux; chief under whom the Sioux tribes of the North American Great Plains united in their fight for survival, including at the Battle of Little Bighorn

In both Colonial America and the growing United States, native voices impacted the unfolding of historical events — and these voices remain integral to our American story today. But as this story was first being written, it was done so in a one-sided manner — by white settlers, that often gave little thought to the lives and intentions of those whom they came to view as enemies. As such, the lack of Indigenous perspectives created a gap in the historical narrative — one that the American Battlefield Trust aims to carefully fill in the context of America’s first century of conflict.

The Trust’s ever-growing library of biographies provide insight on Native American leaders and notable figures involved in such conflicts. While such biographies are written narratives, it is acknowledged that, for many Native American people, the oral tradition is the primary means of transmitting and understanding history. This acknowledgement also carries the promise to further our work and incorporate direct quotes and other elements from oral narratives, which will lead us to a more inclusive view of Native American stories.

Explore Biographies

Spurred by intrusive policies that violated earlier treaties, the Ottawa Chief Pontiac led a rebellion to demonstrate vast discontent.

Location: Current-day site of Fort Detroit in Detroit, Mich.

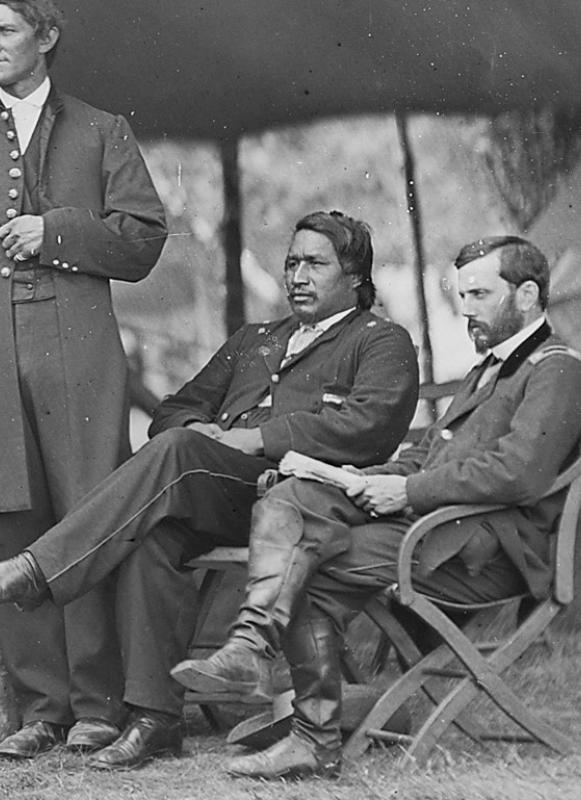

The only Native American general during the Civil War, Stand Watie led the 2nd Cherokee Mounted Rifles at the Battle of Pea Ridge.

Location: Pea Ridge Military Park in Garfield, Ark.

Joseph Brant sided with the British during the American Revolution, eventually being deemed "Captain of the Northern Confederated Indians."

Location: Fort Stanwix Natl. Monument in Rome, N.Y.

Menawa was a polarizing political figure amongst the Creeks during the tribal disintegration of the early nineteenth century.

Location: Horseshoe Bend Natl. Military Park in Daviston, Ala.

Sacagawea took on the role of guide, interpreter, and diplomat during the Lewis and Clark Expedition of 1804-06.

Location: Sacajawea Historical State Park in Pasco, Wash.

Black Kettle helped negotiate several treaties in the mid-1800s, transforming lives for Native Americans across the nation.

Location: Washita Battle Natl. Historic Site near Cheyenne, Okla.

Against settler expansion onto Native lands, Tecumseh took a variety of steps — including alliance building — to demonstrate his opposition.

Location: Tippecanoe Battlefield Park in Lafayette, Ind.

A bridge builder between the British and Native peoples, Butler served the British and fought alongside Native American soldiers during the Revolution.

Location: Wyoming Monument in Wyoming, Pa.

A spiritual leader of the Shawnee, Tenskwatawa established Prophetstown in 1808, along with his brother Tecumseh.

Location: Prophetstown State Park in West Lafayette, Ind.

Polly Cooper was an Oneida woman who proved invaluable to the Continentals during the American Revolution.

Location: Valley Forge Natl. Historical Park in King of Prussia, Pa.

A vital leader in Company K of the 1st Michigan Sharpshooters, Graveraet grew up navigating the middle ground between two worlds.

Location: Petersburg Natl. Battlefield in Petersburg, Va.

Little Turtle was victorious against the U.S. Army on multiple occasions, eventually agreeing to peaceful cooperation with the U.S.

Location: Fort Recovery State Museum in Fort Recovery, Ohio

A Lakota leader who resisted removal to the reservation, Sitting Bull was a major player in the Battle of Little Bighorn.

Location: Little Bighorn Battlefield Natl. Monument in Crow Agency, Mont.

Resisting government threats and removal to reservations, Chief Crazy Horse became a pivotal leader in his people's difficult plight.

Location: Fort Robinson State Park in Crawford, Neb.

Parker was a leading Seneca who made a big mark on history by serving alongside Ulysses Grant during the Civil War.

Location: Appomattox Court House Natl. Historical Park in Appomattox, Va.

Nimham was a protector of his fellow Wappinger in the Hudson River Valley, and eventually fought alongside the Patriots in the American Revolution.

Location: Chief Nimham Memorial in Bronx, N.Y.

Daughter of Chief Powhatan, Matoaka (Pocahontas) became a legendary intermediary between her people and the Virginia colonists.

Location: Pocahontas Memorial Statue in Williamsburg, Va.

Colonization & Revolution

“The Mohawks have on all occasions shown their zeal and loyalty to the Great King; yet they have been very badly treated by his people.”

Joseph Brant (Thayendanegea): Mohawk warrior, tribal leader, and diplomat most notable for his alliance with the British during the American Revolution

As Europeans strove to gain more land and control on the American continent in the colonial period, Native Americans found ways to resist these European efforts — through diplomacy, war, or alliances — but struggled amidst new diseases, the slave trade, advanced weaponry, and a constant influx of European colonists. And as European nations rushed to stake their claims on already-inhabited land in the Americas, Native American nations carefully allied themselves with the European power they believed would give their people the best circumstances. For instance, during the French and Indian War of 1754-1763, the Iroquois Confederacy allied with the English while the Algonquian-speaking tribes joined forces with the French and the Spanish. Regardless of the English victory, aggression against Native Americans continued as Europeans continued to flock to the continent. And as neighboring tribes had been pitted against each other through their claimed alliances with Europeans, rifts were built that kept tribes from uniting to halt the European advance.

And when American colonists rose up against the British Crown during the Revolutionary War, this conflict not only determined the future of the colonies — but also the future of the native peoples who lived in and around them. Again, tribes would be drawn into the conflict, forced to make difficult decisions about how and when to offer their support.

Early American Frontier

"I am Shawnee! I am a warrior! My forefathers were warriors. From them I took only my birth into this world. From my tribe I take nothing. I am the maker of my own destiny!"

Tecumseh: Shawnee warrior chief who organized a Native American confederacy in an effort to stymy settlement in the Northwest Territory, as well as a British ally during the War of 1812

Native Americans played a major role in the War of 1812. Tribes aligned with both sides of the conflict, although the majority allied themselves with the British over the Americans. Native American forces fought on the frontier and along the Gulf Coast during the war, with many also swept into battle by tribal wars that took place simultaneously. Impactful Indigenous leaders included Tecumseh, a Shawnee Chief who supported the British during the war and organized a confederation of tribes in the Great Lakes region, known as Tecumseh’s Confederacy, to resist ongoing encroachment on their lands by white settlers. Tecumseh was killed at the Battle of the Thames, which led to the subsequent downfall of his Confederacy. Like Tecumseh, Black Hawk —a Sauk Chief — supported the British as he feared the growing influx of settlers into Sauk territory. During the war, Black Hawk fought against American frontiersmen — continuing in the task even after the war ended. To protect his people, he organized a new confederacy, bringing forth the Black Hawk War of 1832.

With the end of the War of 1812, many tribes could no longer look to Great Britain to shield them from the flood of white settlers headed west. Settlers came in droves by the Erie Canal or through the Cumberland Gap. The next seventy-five years saw a rapid decline in the Native Americans' way of life, even for those tribes like the Cherokee or Choctaw that had adopted not only materials goods brought by white settlers, but also beliefs and other ways of life. Manifest Destiny ultimately ruled the day as treaties and military force dictated tribal migration — and removal — north of the Ohio River.

Civil War and Aftermath

“The sky has been dark ever since the war began. We want to take good tidings home to our people, that they may sleep in peace.”

Black Kettle: Cheyenne chief who was committed to peace, attended several councils, and even maintained a determination for peace after the tragedy he experienced because of the Sand Creek Massacre of 1864

Not only a divisive conflict between the Union and the Confederacy, the Civil War also severed Native American nations, communities, and families, as it extended into the western frontier. Approximately 20,000 Native American soldiers partook in the war, and on both sides. At first, many native nations in the west’s “Indian Territory” signed treaties with the Confederacy, but many tribes also had great sympathy for the cause of abolition and favored sovereign independence from the country and its chaotic conflict. As the war continued, three Indian Home Guard regiments surfaced in support of the Union and with eyes toward protecting their tribal communities. As was the case with the Revolutionary War and War of 1812, the Civil War yet again drove Native Americans to fight against each other on the basis of their allegiances.

Whatever reason drove native soldiers into the fold of war — whether it was to support or fight slavery, to defend tribal sovereignty and to protect family and community — the conflict didn’t help the Native American nations involved. It took tribal tensions to an all-time high while destroying land that the U.S. government had relocated natives to decades earlier, molding a sad, impoverished future for many Native Americans out west.