Great Britain was determined to respond to France’s military expansion into the Ohio River Valley in 1754. The year’s attempt to capture and build a fort at the Forks of the Ohio River, where the Ohio, Monongahela, and Allegheny Rivers meet (present-day Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania), had failed miserably as young Colonel George Washington was forced to surrender at the Battle of Fort Necessity and head back to Virginia under the promise that he and his men would not return to the region for a year. This setback, however, was not enough to deter King George II from asserting his influence in North American on land that he rightfully believed belong to the Crown.

Britain’s military strategy for 1755 would not solely focus on recapturing the Ohio River Valley. A four-pronged thrust by British regular soldiers and colonial provincials (American colonists) into regions occupied by French troops in western Pennsylvania, Nova Scotia, and Upstate New York would be utilized. The main offensive, however, would be against Fort Duquesne, the French fort situated at the Forks of the Ohio.

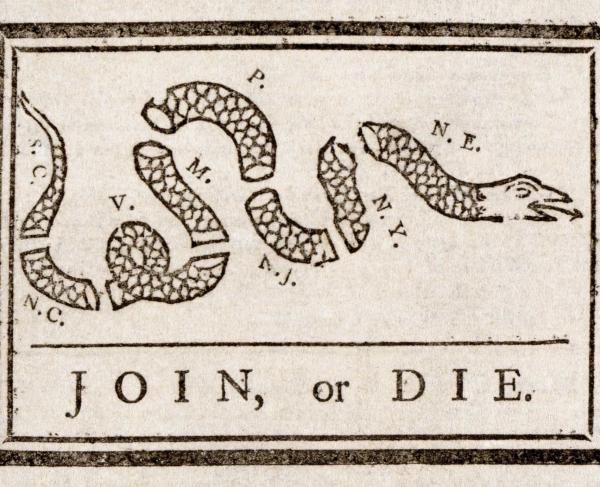

The man tasked with subduing the enemy in western Pennsylvania was Major General Edward Braddock, a career army officer. He was appointed commander in chief of His Majesty’s Forces in North America and arrived in Hampton Roads, Virginia in February 1755 with a mission of “the greatest importance,” according to the Captain-General of the British Army, the Duke of Cumberland. In April, Braddock met with some of the colonial governors in Alexandria, Virginia, and laid out his plans for the various expeditions and what he expected of the colonists. The royal governors were not as eager to open their purses to him as he had hoped, and a feeling of contempt towards the colonists began to grow within him. Their cooperation and assistance would be crucial, however, as Braddock would need to carry an army of 2,400 British regulars (44th and 48th Regiments of Foot) and colonial troops (Maryland, New York, North and South Carolina, and Pennsylvania) three-hundred miles through the wilderness, mountains, and occupied enemy territory, a much larger force than had been sent to the Forks the previous year. It was quite an intimidating logistical operation.

The first destination for Braddock’s expeditionary force was Fort Cumberland (present-day Cumberland, Maryland), which was established as a main base of operations to send troops into western Pennsylvania. To reach Fort Cumberland, the army used two separate routes, splitting at Alexandria and marching to Frederick, Maryland and Winchester, Virginia. Braddock personally traveled with the wing of his army that moved to Frederick before heading south to rendezvous with the men at Winchester. Accompanying Braddock as a volunteer aide was 23 year old George Washington, eager to redeem himself and return to the Ohio River Valley.

While in Maryland, the general met with Pennsylvanian Benjamin Franklin, who was able to procure his force some desperately needed wagons, which the colonial governors had failed to deliver him. For an army on campaign, wagons carried everything that was needed for it to sustain and succeed. Such an arduous trek as Braddock was undertaking would leave many wagons broken or lost to the elements and nature. He needed all the wheels he could get.

After the meeting with Franklin, Braddock continued on in late April and crossed South Mountain with Colonel Thomas Dunbar’s 48th Regiment before turning south for Winchester and the main bulk of his army there, including the majority of his supply wagons and artillery. Dunbar’s men advanced to present-day Williamsport, Maryland, where they crossed the Potomac River to begin a 129-mile march to Fort Cumberland.

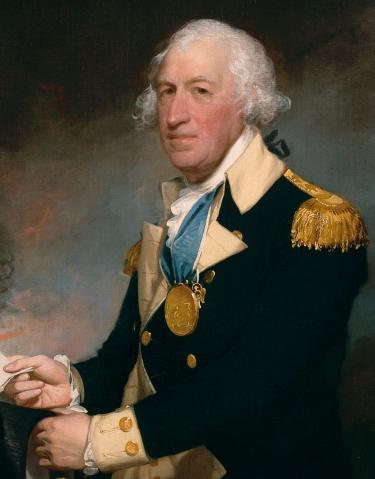

On May 10, after traveling along a 97-mile road that had been hastily built by Deputy Quartermaster General Sir John St. Clair, Braddock, Colonel Peter Halkett’s 44th Regiment, and the colonial provincials began arriving at Fort Cumberland. After Dunbar’s wing entered the camp, the army was divided into two brigades commanded. Halkett led the First Brigade, which consisted of his own 44th Regiment (700 men strong), four companies (about 50 men each) from Maryland and Virginia, and one composed of New Yorkers under the command of Captain Horatio Gates, the future victor of the Battle of Saratoga in 1777 during the Revolutionary War; the Second Brigade was led by Dunbar, made up of his 48th Regiment of Foot, serving as its nucleus, and six companies from the Carolinas. Twenty-seven cannon of various sizes completed the army. It was quite an impressive force, but it lacked one important thing that the French at Fort Duquesne did not: Native Americans.

General Braddock’s lack of Native American support has been accepted as at his own doing. While meeting with representatives of the Ohio River Valley tribes at Fort Cumberland, Braddock greatly angered and offended them by supposedly claiming that after the French were driven from the region, “No savage should inherit the land.” The French were much warmer in their reception of the indigenous inhabitants, and they turned their backs on the British. Only eight warriors stayed behind. In his original orders to Braddock before he traveled across the Atlantic Ocean to Virginia, the Duke of Cumberland had urged him to win over the Native Americans from the French and earn their support for the expedition. In this, Braddock had failed. On May 29, when the army departed Fort Cumberland to begin the final 110 miles of their journey to Fort Duquesne, it was without the best scouts and wilderness fighters on the continent.

As the British column drew closer and closer to the Forks of the Ohio River, 1,400 men were sent ahead as part of a “flying column,” to strike the enemy as fast as possible while the remainder of the force remained behind with Dunbar. The forward column moved much faster than the rear, and because of this, the latter was nearly sixty miles away and out of supporting distance should the former come under attack. With flags flying and fife and drum beating “The Grenadier’s March,” Braddock and the forward column splashed across the Monongahela River with no regard toward maintaining secrecy. Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Gage was sent speeding ahead with a hand-picked body of men from various units. Only several miles from the fort, Gage was attacked by 900 Canadian marines, militia, and French-allied Native Americans (Ottawa, Shawnee, Delaware, and Mingos) under Captain Daniel Beaujeu. The two forces collided with a fury, and Beaujeu, bare-chested and covered in war paint, was struck by a British bullet and killed instantly. Confusion then mounted amongst the Canadians, but the Native warriors took cover within the woods on both sides of the road, fighting back in their traditional irregular way against the long, compact enemy column before them. The British crumbled under the immense pressure from an enemy on all sides they could not see and retreated down the trail. They collided with the second half of the column moving towards the sound of the guns. Pandemonium erupted as Braddock urged his men to fight in a linear style in the road as opposed to adapting to their environment and combating the Canadians and Indians in a similar manner. Casualties mounted as the road was turned scarlet red and blue by the coats of the British regulars and colonial dead and wounded. Bravely trying to maintain order and rally his men to stand and fight, General Braddock was severely wounded. The whole army fled the field and rushed to the safety of Dunbar’s camp. After several hours of bloody combat, the Battle of the Monongahela was over and nearly 900 British and provincial soldiers were killed, wounded, captured, or had gone missing. The horror of the battle did not end there, as the French-allied warriors swarmed the road to claim their prizes of plunder. The wounded were not spared the hatchet. This was the true nature of warfare in North America that Braddock and the British regulars who had traveled here to fight with him were unaccustomed to.

In the days that followed the disaster, the army retreated to Fort Cumberland, but Braddock would never reach there. He succumbed to his wounds and died on July 13. A funeral was held the following day as he was laid to rest in the middle of his road. George Washington—who had escaped the battle unscathed despite being in the thick of it—read a short sermon. Along with Braddock, Col. Halkett was also killed, leaving Dunbar in command of the army. Rather than reorganizing his troops and seizing the initiative to strike at the French again and possibly turn a disaster into a triumph, he pulled his army all the way back to Philadelphia and chose to go into winter quarters. This decision left the Maryland, Pennsylvania, and Virginia frontiers wide open to French and Native American raiding parties. The British settlers in these western parts of the colonies were at the mercy of the enemy for the next several years until the British again marched an army to attack Fort Duquesne and finally oust the French from the Ohio River Valley.

Further Reading:

- The Indian World of George Washington: The First President, the First Americans, and the Birth of the Nation By: Colin G. Calloway

- Drums In The Forest: Decision At The Forks By: Alfred Proctor James and Charles Morse Stotz

- Braddock's Defeat: The Battle of the Monongahela and the Road to Revolution By: David L. Preston

Related Battles

1,000

90