The Revolutionary War did not only determine the future of the American colonies, but it also shaped the future of the Native peoples who lived in and around them. Native Americans were not passive observers in the conflict. While most Native communities tried to remain neutral in the fighting between the Crown and its colonists, as the war continued many of them had to make difficult decisions about how and when to support one side or the other.

Even before the outbreak of war, the colonists were angered by the ways that the British government tried to manage the relationship between its colonists and Native Americans. The British were concerned by violence between white settlers and Native peoples on the frontiers and attempted to keep the two groups apart. The Proclamation of 1763 reserved the lands west of the Appalachian Mountains for Native Americans, which the colonists resented. When the Second Continental Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence in July 1776, among the charges levied at King George III was that he had “endeavored to prevent the population of these states.”

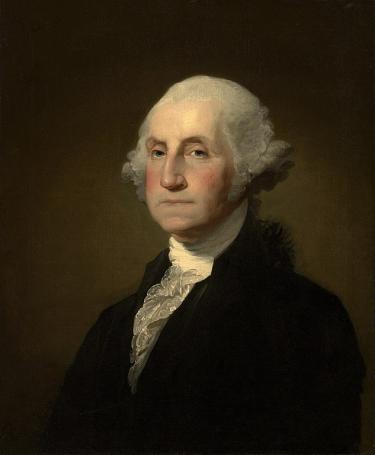

Another grievance in the Declaration of Independence was that the King and his government had “endeavored to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages.” Many rebel colonists assumed that Native Americans would naturally be allied with the British. But most Native communities tried to avoid getting involved in what they saw as a family dispute between the King and his subjects. But both the British and the Americans sought out Native allies throughout the conflict. Officers in both armies, including General George Washington, had fought in the French and Indian War. They had learned to appreciate the value of Native warriors, who had acted as scouts for European armies and launched devastating raids on the colonial frontiers.

Among the first Native Americans to take part in the Revolutionary War actually joined the rebel side. The Native community at Stockbridge, Massachusetts, sent seventeen men to join the army of militiamen that was laying siege to Boston in 1775. Other Native Americans joined the British side and fought to defeat the American invasion of Canada in 1775-1776. Native communities did not always make unanimous decisions about which side to support. The Cherokee nation was split between a faction that supported the colonists and another that sided with Britain. The Iroquois Confederacy, an alliance of six Native American nations in New York, was divided by the Revolutionary War. Two of the nations, the Oneida and Tuscarora, chose to side with the Americans while the other nations, including the Mohawk, fought with the British. Hundreds of years of peaceful coexistence and cooperation between the Six Nations came to an end, as warriors from the different nations fought one another on Revolutionary War battlefields.

Britain had an advantage in convincing Native Americans to fight on the side of the Crown. British policies before the war had tried to limit the encroachment of white settlers onto Native lands, while American colonists were eager to expand westward. Britain also maintained a network of forts and trading outposts on the frontiers, like Fort Niagara and Fort Detroit. From these bases, British officers could encourage groups of Native American warriors to launch devastating raids on communities that supported the American cause. Oftentimes these warriors were accompanied by American Loyalists who had been forced to flee those communities. These raids led to harsh retaliation. In 1779, General George Washington dispatched an expedition under General John Sullivan into Iroquois country to destroy Native villages and crops. The expedition was one of the largest and most meticulously planned operations that the Continental Army undertook during the war. The objective of the campaign was to stop the raids by burning Native villages and crops, and it earned Washington the Iroquois name of “Town Destroyer.”

While many Native Americans fought with the British, battles on the frontiers involved very few professional British soldiers. Most of the fighting was between Native warriors, American Loyalists, and rebel militia. This war did not end when General Cornwallis surrendered at Yorktown in 1781. In fact, as the war east of the Appalachians came to an end, the war on the frontiers became more intense; 1782 became known as the “Bloody Year.”

While the Revolutionary War cost Britain the Thirteen Colonies, it cost Native Americans much, much more. In the peace treaty, in addition to recognizing the independence of the United States, the British ceded to the new nation all British territory east of the Mississippi and south of Canada. This decision was made without any input from the Native Americans who lived on those lands, most of whom had chosen to side with the British precisely because they wanted to block further white settlement. When settlers did flood into the newly acquired territory, many of them justified harsh treatment and expulsion of Native Americans with the belief that all Native peoples had supported the British during the war. When Native Americans fought back against the United States, they found very little support from their former British allies.

Native Americans played a major role in the Revolutionary War, a role that is often minimized or misunderstood. Including them in the history of the war is crucial to understanding the full story of the founding of the United States.

Further Reading:

- The Indian World of George Washington: The First President, the First Americans, and the Birth of the Nation By: Colin Calloway

- Scars of Independence: America’s Violent Birth By: Holger Hock

- Masters of Empire: Great Lakes Indians and the Making of America By: Michael McDonnell

- Facing East from Indian Country: A Native History of Early America By: Daniel Richter