Native Americans and the Call to Serve

There is no doubt that American Indians have been dealt a complex and difficult past in this nation, but that has not deterred many from military service. In fact, today American Indians and Alaska Natives serve in the armed forces at a rate five times the national average. Members of these groups have served with distinction in every major American conflict for over 200 years.

Revolutionary War War of 1812 Civil War WW IWW IIVietnam War Present

It can be hard to remember that American Indians fought both against and alongside Patriot forces in the Revolutionary War. That is, in part, because the nation’s founding document, the Declaration of Independence, painted American Indians as destructive pawns of King George III and didn’t account for the full picture.

They were not pawns in the least bit; tribes exercised autonomy as they sided with those whom they believed would provide the greatest chance of protecting their native lands. For instance, the Revolution divided the Iroquois Confederacy. Mohawks and many Cayugas, Onondagas, and Senecas stood beside the British while the Oneidas and Tuscaroras sided with the Americans. In New England, there was much tribal support for the colonists, including those from the mission town of Stockbridge, Mass., who stepped up to serve as Minutemen before the war’s official outbreak — who joined the fledgling American army at the siege of Boston — and who saw battle in New York, New Jersey, and Canada.

Despite service on both sides, American Indians and their native lands were not considered in the Treaty of Paris, in which Britain ceded to the newly established United States its territory east of the Mississippi, south of the Great Lakes, and north of Florida. As the new nation expanded, these native lands were often lost — whether by treaty or by force.

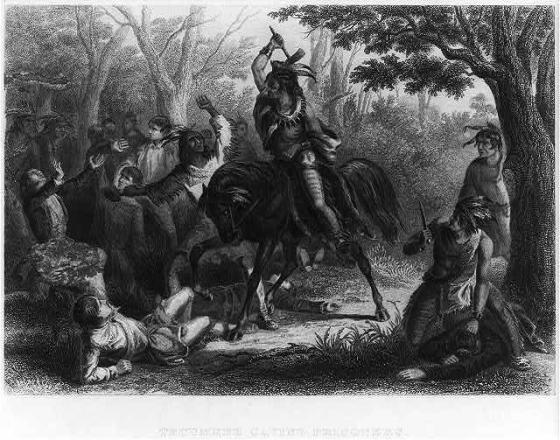

Mirroring the Revolution — and, in fact, the French and Indian War during the Colonial Era — American Indian tribes aligned with both sides during the War of 1812, although they predominately sided with the British, believing that a British triumph might signal the end of American expansion. Tribes fought along the frontier and the Gulf Coast. At times, tribal wars occurred alongside battles of the War of 1812. A well-known Native American ally of the British was Tecumseh, a Shawnee leader who organized a confederation of tribes, known as Tecumseh’s Confederacy, to resist ongoing encroachment on their lands by American settlers. These troops famously clashed with American forces under future president and general William Henry Harrison at Tippecanoe in 1811. On the contrary, more than 1,000 American Indians fought on behalf of the Americans during the war. A contingent of Choctaws even fought alongside then Maj. Gen. Andrew Jackson at the Battle of New Orleans. In addition to Choctaw forces, Creeks, Cherokees, Chickasaws, Shawanos, and Stockbridges were among the tribes organized into more than 100 companies, detachments, or parties battling on behalf of the Americans. There are even service records for many of these native soldiers in the National Archives.

There were roughly 20,000 American Indians who served in the Union and Confederate armies during the Civil War. After experiencing extensive discrimination and removal from ancestral lands, tribes sought to better their circumstances through strategic alignments. American Indians experienced battle at such places as Pea Ridge, Spotsylvania, Cold Harbor and Petersburg. Tribes like the Pamunkey in Virginia were loyal to the Union, putting their lives at stake to serve as pilots and scouts on gunboats travelling Virginia waterways. And you can also make note of Company K of the 1st Michigan Sharpshooters, consisting of 139 Ojibwa, Odawa, and Potawatomi warriors who fought with Grant’s army at the Wilderness and Spotsylvania. Formed in 1863, the American Indian men of Company K wished to enlist earlier but had been denied.

The mentality of Company K embodied that of many of the Native Americans who chose to serve — by demonstrating loyalty on the battlefield, they hoped to be rewarded off of it. Instead, the United States government continued to implement policies that removed American Indians from their ancestral homes. Battles of the ongoing American Indian Wars at-times collided with those of the Civil War as the great push of American westward expansion wasn’t put on hold during the clash of the Union and Confederacy. And after Union victory, such conflicts became an even greater focal point, of which resulted in devastating losses for American Indian communities.

When the United States entered into the First World War in 1917, approximately a third of American Indians weren’t seen as United States citizens. Despite this, they were still plunged into the draft, a decision of the United States Government that resulted in extensive confusion, resentment, and even rebellion in the American Indian community. However ill-received the draft was, roughly 6,500 American Indian men were conscripted and more than 5,000 others enlisted — many likely hoping that their service would equate to U.S. citizenship. Fourteen American Indian women even volunteered to support the international conflict with the U.S. Army Nurse Corps, with two of them — Cora E. Sinnard of the Oneida tribe and Charlotte Edith of the Mohawk tribe — working in military hospitals in France.

A sizable number of American Indian troops gravitated to positions as snipers and scouts, risky tasks that resulted in five percent losing their lives. An advantage that some brought to the fight was the use of their native tongues — Cherokee and Choctaw troops upheld the integrity of communications in the face of German interference by transmitting in their native languages.

At long last, American Indian service in the United States military was recognized and rewarded. Native veterans were granted citizenship in 1919, with all American Indians following in 1924.

During the Second World War, American Indians stepped up in large numbers — out of approximately 350,000 in the nation, an astounding 45,000 enlisted for military service. There were some tribes that witnessed as many as 70 percent of their men join the armed forces. Native women were also included in those who served, working largely with the Women’s Army Corps.

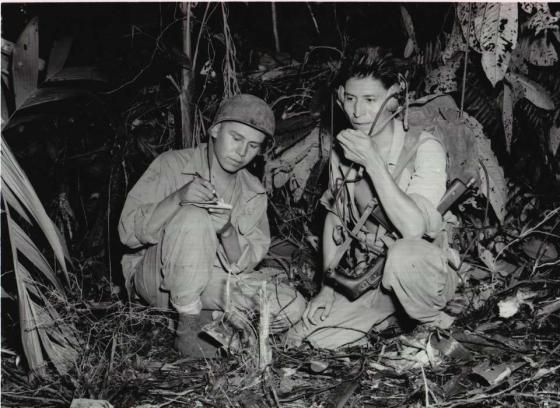

The advantageous use of native languages continued on in this conflict, with those who transmitted these messages known as “code talkers.” Such recruitment began in the U.S. Army in 1940, and by 1942, upon the recruitment of several Navajo, the Marine Corps launched a code-talking school. In addition to basic training, these Navajo recruits were required to develop and memorize a distinct military code by means of their mostly unwritten language. Their skills proved essential, with code talkers playing a role in both the D-Day invasion in Normandy and at Iwo Jima in the Pacific. Maj. Howard Connor, a 5th Marine Division signal officer, even claimed, “Were it not for the Navajos, the Marines would never have taken Iwo Jima.” And Marine Corporal Ira Hayes, a Pima man, was immortalized when he and five others were photographed raising the U.S. flag on Mount Suribachi at Iwo Jima.

Even though the bravery and integral role of the American Indian code talkers was noted internally by the military, the program was not declassified until 1968; and even with that, Congressional Gold Medals were not given to the Navajo and other code talkers until 2001. Chester Nez, a Navajo who served in both World War II and the Korean War said that many people were curious about his motivations. “People ask me, ‘Why did you go? Look at all the mistreatment that has been done to your people.’” To which Nez would respond, “Somebody’s got to go, somebody’s got to defend this country. Somebody’s got to defend the freedom.” And defend it they did; American Indians earned a combined 71 Air Medals, 34 Distinguished Flying Crosses, 51 Silver Stars, 47 Bronze Stars and seven Medals of Honor during the conflict.

Despite a prevalent and unpopular draft, 90 percent of American Indians who served in Vietnam volunteered to do so. A rough total of 42,000 American Indians joined the armed forces during the conflict, although this is a tribal estimate that may exclude residents of urban or non-reservation areas and members of tribes not recognized by the federal government. Many volunteered because of opportunities that military service presented in contrast to the cycle of poverty many experienced on reservations. Additionally, some simply saw service as a way of demonstrating patriotism or — reflecting the motivation for native service in past wars — a path to continuing warrior traditions. Ultimately, 232 American Indian and Alaska Natives perished in the conflict — their names forever remembered on the wall of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. Two Cherokee members of the U.S. Navy, James Williams and Michael Thornton, earned the Medal of Honor for valorous actions.

Common among American Indian veterans who served was a feeling of remorse and déjà vu — that these actions played out by the United States military in Vietnam were eerily familiar. Some viewed these actions through the lens of the American Indian past — as an invasion into territory that didn’t belong to them, followed by the taking of land. Many were left deeply troubled by these parallels.

In the 1980s and 1990s, American Indians jumped into service in such places as Grenada, Panama, Somalia, Bosnia and Kosovo and the Persian Gulf. Continuing into the 21st century, they served in Afghanistan and Iraq. After September 11, 2001, about 19 percent of American Indians went into the armed forces — a higher percentage than any other ethnicity. As of 2017, there were more than 31,000 active-duty service members who identified as American Indians and Alaska Natives — out of over 1.2 million in total. And of today’s living veterans, over 140,000 are said to be of native heritage. To add to that, of these veterans and active-duty service members, almost 20 percent are women. Of the many losses these conflicts generated, the first woman killed in action Operation Iraqi Freedom was Private First-Class Lori Piestewa of the Hopi tribe.

Looking to honor all native veterans, the National Native American Veterans Memorial will be dedicated on Veterans Day 2020. A Cupig and Yupik veteran of Bosnia and Afghanistan, Colonel Wayne Don has expressed enthusiasm over the potential insight that the memorial can convey, saying “I guess I want people to recognize how often Native people have volunteered. From Alaska to the East Coast, through all the wars, Native people have always volunteered.”

A virtual program will be held on Veterans Day to mark the completion of the memorial and recognize the service and sacrifice of Native veterans and their families. For more information on this virtual program and to view the online exhibit “Patriot Nations: Native Americans in Our Nation’s Armed Forces,” visit the National Museum of the American Indian’s website at https://americanindian.si.edu/.