Unearthing Relics of War and Finding Peace

In cooperation with the American Battlefield Trust, a new veteran-led organization is bringing former service members suffering from PTSD and other disabilities to historic battlefields. Through the process of rehabilitation archaeology, we are learning more about past wars and offering healing to today’s warriors.

When lights begin to appear in the windows of the rented home in upstate New York, dawn has yet to penetrate the forested landscape. Those inside may not all share blood, but they are tied together by a different sort of unbreakable bond. And, though they met as strangers, when their time here ends, they will consider each other family.

For four weeks in May and June 2019, this place is home base for a crew of some 30 veterans from the conflicts in Vietnam, Iraq and Afghanistan — many of them disabled physically or psychologically — brought together by American Veterans Archaeological Recovery (AVAR), a nonprofit dedicated to promoting the well-being of disabled veterans transitioning to civilian life through field archaeology. They have come to assist the National Park Service (NPS) in its investigation of a key site associated with the Revolutionary War Battle of Saratoga, serving in two different teams to gain exposure to all aspects of the archaeological process — from high-tech surveys, to physical excavation, to the careful recordation of data.

While AVAR has previously been able to bring participants to archaeological sites in America and military sites overseas, this is the organization’s first opportunity to explore hallowed ground in its home nation.

“To dig in an actual historic American battlefield … warrants that sense of ‘more’ that you get from being in the military,” acknowledges participant Zeth Lujan, an Army combat veteran. “You think about how millions of people have worn that uniform. And that millions are going to come after us, after our service is done.”

A combat veteran standing on a historic battlefield has a vastly different experience than someone who has never come under fire. Not only do they instinctively connect with that landscape in terms of military science — scanning for defensible positions, mapping out avenues of approach — they can imprint their own field experience unto soldiers of the past. To a veteran, the thousands of soldiers who waited for an order to charge aren’t statistics in a history book, they are fully realized individuals. The soldiers they envision wear the faces of real-life comrades, friends they lost on the fields of Iraq or the mountains of Afghanistan, even if they carry a musket and powder horn.

“When I first set foot on the Saragota Battlefield, it took me back,” says Gunnery Sgt. Oscar Fuentes, who is still an active duty Marine, although his wife has completed her service and they participate in AVAR together. “I could imagine those soldiers getting ready for that battle. I remember what I would do the night before going forwards, how I felt when we were at base camp. I know that feeling: thinking that tomorrow is uncertain. The weaponry does not compare to what we have now, and the tactics are way different. But that feeling is overwhelming. I can imagine myself on that battlefield.”

Bringing veterans to such a place is a powerful goal in itself, but by letting them physically delve into the past, AVAR is a means for today’s warriors to reach out and touch the soldiers who came before them. To tell their stories through these tangible artifacts left be-hind. And in doing so to discover something new about themselves.

“To dig up a button or something that an American militiaman actually wore on his uniform, it blows my mind,” says retired Air Force Captain Karen Reed of Sandia Park, N.M., an AVAR rookie on her first dig. “As a war veteran, that’s my heritage, because we trace our military lineage back to those militias. So to be able to sit under a tree where a first American — not a British colonial, but an American — sat, and most likely died, in that fight for us is a very, very sobering feeling.”

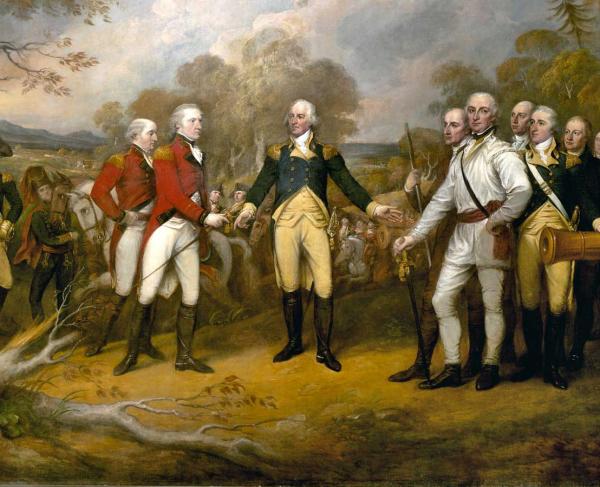

If there are certain points in time upon which history hinges, one of them undoubtedly occurred in the autumn of 1777, on bluffs over the Hudson River, near the modern village of Schuylerville, N.Y. Following two engagements fought here at Freeman’s Farm and Bemus Heights, British General John Burgoyne surrendered his command to the Continentals under General Horatio Gates on October 17. It was the first time an entire British field army had ever capitulated, and the unprecedented event caught the attention of King Louis XVI, resulting in the formal allegiance of France to the American cause. This international support, which later came to also include the Spanish and Dutch, was instrumental in securing the American victory.

Despite the broad sweep of the battle being well understood, many specifics have been lost to time, a typical situation with engagements from this period. Thanks to a confluence of factors, Revolutionary War battles are relatively undocumented, compared to those of later eras. No robust system of after-action reports by officers at all levels had yet been implemented in either army. Lower literacy rates among enlisted soldiers during the 18th century means fewer letters and diaries to draw from. Lack of technologies like photography — to capture landscapes and landmarks — or lithographic printing — to mass-produce what sketches and maps were recorded in the aftermath — also play a role. Then there is the simple passage of time: two-and-a-half centuries is ample time for what documentary evi-dence was created to have been lost.

One of those missing moments is the fight for the Barber Wheatfield, the opening clash of the Second Battle of Saratoga on October 7, 1777. Some things are certain: British and German troops advanced into the field to gather food. They were met by an aggressive advance, as American troops pushed out from their fortified position and drove the British back to their lines. The fighting was fierce: In less than an hour, the British lost 90 dead, 180 wounded and 180 captured, while the Americans suffered 150 total casualties.

Beyond that? Plenty of mystery.

Enter archaeology, a scientific process that can turn the battlefield itself into a powerful primary source. Surveying a battlefield may uncover both revelatory individual artifacts and distribution patterns that imply specific scenarios. A heavy, linear concentration of unimpacted musket balls could indicate where troops were positioned, as many soldiers accidentally dropped ammunition while they sought to reload. The scatter pattern of artillery fragments can be analyzed to triangulate where a battery was placed.

And while analysis has been conducted for some portions of the battlefield, and significant findings have been recorded, experts agree that much work remains to be done. It’s simply a matter of finding the means — the time, the team, the funding — to pursue it.

“We have the historical sources that indicate how the battle unfolded,” said Bill Griswold, who led the Saratoga project on behalf of the Park Service’s Northeast Region Archeology Program. “It’s just that we’ve never been able to really ground proof with features on the landscape. It’s not so much debunking as it is adding additional information to the narrative.”

The opportunity to perform archaeological research on core battlefield land inside a national park is exceedingly rare. Anyone found to be metal detecting or excavating without permit faces jail time and harsh fines, and the National Park Service has a far longer list of potential projects than manpower and funding can accomplish in any given season. With nearly 100 parks and historic sites in the Northeast Region alone, NPS has had to develop a competitive application process to prioritize activities. There can also be hesitancy to disturb the hallowed ground of a battlefield without a compelling case for the research.

“For many years, we have wanted to tackle large landscape surveys of the battlefields to better understand the history and to potentially confirm troop locations and the sites of historic homes,” said Saratoga National Historical Park superintendent Amy Bracewell. “When the American Battlefield Trust reached out to me with the interest to partner with AVAR, I knew this was our moment. This survey is embarking on a completely innovative approach to archaeology, and what better partner than the American Battlefield Trust? The Trust has supported innovative research and land protection approaches since its inception. With AVAR on board, we are able to expand our abilities in battlefield archaeology with veterans who understand intimately the nature of war.”

The work done at Saratoga is a far cry from the stereotypes made popular by Indiana Jones, and involves methodologies made possible by 21st-century technology. The process begins with an aerial survey of the site, in which specially permitted unmanned aircraft systems utilize light detection and ranging (LiDAR) equipment to generate a detailed 3D model of the landscape and capture oblique aerial photography. This process helps identify historical features of the landscape not visible from the ground, including road traces and building foundations.

Next comes a ground survey, conducted by specialists from NPS’s Midwest Archeology Center, in which an all-terrain vehicle tows a specially designed magnetometer with multiple sensors across the landscape. Beyond ground-penetrating radar, this process also captures magnetic gradient, conductivity and multispectral imaging. Then it is time for boots on the ground, as AVAR participants receive training in state-of-the-art equipment with volunteer instructors from Advanced Metal Detecting for the Archaeologist and begin to systematically survey the field.

Only once all of these data are compiled and layered together does anyone lift a shovel, ensuring minimal disturbance of these historic landscapes. Traditional archaeological methods, including the digging of test plots, serve to confirm the initial investigations and carefully extract pre-identified anomalies to determine their nature and significance. Details about each excavated item are carefully logged, ultimately creating the most robust view of the battlefield possible. Further analysis in the lab will aid in verifying — or refuting — troop locations as they are proposed on historical maps.

No one plays Reveille to rouse the AVAR crew, but years spent in uniform make waking with the sun, if not before, feel natural. By 6:00 a.m., the pair on current rotation to prepare breakfast is hard at work. The meal is a communal affair and includes a briefing on expected weather for the day, not to determine whether their efforts could be curtailed, only to assess what gear might be needed to muscle through. Then everyone piles into vehicles for the hour-plus journey — driving is another duty that rotates through the ranks — to the dig site.

At Saratoga, conscious of the physical limitations of some disabled veterans, AVAR staff begins the day with a team stretching session. Fieldwork typically occurs in two-hour blocks, with scheduled breaks for food or rest. Lunch is a longer pause, sometimes with a presentation on how to build a résumé suited for pursuing a career in archaeology, or the benefits of another veteran-focused program that a participant has enjoyed. AVAR pays for participant meals through private donations, but lunches are sometimes donated by local groups; sandwiches may be delivered by a Girl Scout troop, for example.

Conditions, as described by Reed, are all that you would expect for a job that puts you in the thick of the summertime elements, digging in the dirt of an open field: “It’s hot, and there’s ticks, and there’s mosquitoes, and there’s sunburn. And ‘Oh my God, I’m sweating.’ It’s grueling on your knees; you’re up, you’re down. A lot of people out here have bad-news bad joints, so everything hurts.”

Despite the remarkable assistance rendered by modern technologies, the labor required once even limited excavation begins is grueling. “People are surprised at how physically demanding excavations are. It varies a little from one site to the next. But, in general, about 80 percent of a dig is moving dirt with a pickax, a shovel and a bunch of buckets or wheelbarrows; the other 20 percent is fine-detail work,” says AVAR CEO Stephen Humphreys, himself a former Air Force captain and veteran. “When you find something, it’s because you’ve earned it. That difficulty is key for therapeutic impact … a lot of our participants struggle with insomnia, but we find that eight hours of digging will usually cure that.”

AVAR puts into practice the concept of rehabilitation archaeology, which posits that being involved in this veteran-focused group setting can be beneficial to those seeking to reintegrate into civilian life after a military career. By uncovering the stories hidden for more than two centuries, the veterans are playing a role in protecting the battlefield. But, as Humphreys says, “The research that we’re doing also indicates that that battlefield is saving our veterans."

And America’s veterans need saving. According to a survey by the RAND Center for Military Health Policy Research, almost one-third of those who have returned from deployments in the 21st century suffer from the invisible wounds of mental illness or traumatic brain injury directly tied to their service. Worse still, only half of those who suffer from these conditions seek medical help for them — and only half of those receive fully adequate care. Even those whose experiences have not resulted in diagnosable mental health conditions face an uphill battle to rein-tegrate into civilian life.

In quantitative terms, AVAR utilizes the Department of Defense’s Pain Assessment Screening Tool and Outcomes Registry survey to measure the program’s physical and mental impact. But AVAR management emphasizes that qualitative measures specific to individuals are far more important to them. “We’re vets too, so our participants are like family to us. If one of our participants who was previously isolated and spending most of their time on a couch starts a degree program after going on a dig — even if that degree isn’t in archaeology — we call that a win,” says Humphreys. “If a vet who felt lost and alone, and was contemplating becoming one of those 22 who take their own life every day, comes out of a dig with a new group of people who have their back, that’s a huge win.”

Participants inherently recognize that community is the very heart of the AVAR experience, far more so than any scientific study. “I’ve learned a lot of history, yes,” says retired Army sergeant Tom Wyatt. “But I’ve also learned that I have not lost my ability to connect with other soldiers — the camaraderie is not gone. A lot of times, when you get out of the service you get into your own rhythm, and you start doing other things with your life. When you look back, you think there’s an esprit de corps that is lost. And if you come into a situation like this where you’re surrounded with soldiers again, it’s powerful because you realize that aspect of your life is not gone.”

The experience resonated powerfully with Nichol Fuentes, who went from being a Marine sergeant to a medically separated veteran to a first-time digger to AVAR’s chief operating officer. “For two years, I was floundering around. When you get out of the military, you kind of lose yourself a little bit. I missed being in a group, being in a unit. But through AVAR, I’ve learned that I’m strong. And I can still give 110 percent even though I’m a disabled veteran myself.”

While most AVAR participants would classify themselves as armchair historians — after leaving the field, if not before their arrival in the program — a handful are actively interested in archaeology as a long-term career, Zeth Lujan among them. He is pursuing an undergraduate degree in archaeology, technology and historical structures from the University of Rochester, and traces his love of the field to deployment with the 10th Mountain Division in Afghanistan in 2011–2014. So historic was the area in which they were stationed that his unit had standard operating procedures in place for dealing with cultural resources.

“I remember reading once that just one percent of U.S. citizens go into the military. That statistic also applies to people as they transition back,” says Lujan. “There’s this disconnect, almost a stigma, when you get out of the military, especially if you’re going to college. Some people thinking how you could have done something different but instead you chose that. And with AVAR, you’re sur-rounded by like-minded people that have that same approach to work — the same motivation and focus — that you do. You know you all signed the dotted line, embraced the suck, and now you can come here and do this.”

For nearly all participants, “this” — that transformative moment that Lujan speaks of with awe — is when an artifact emerges from the ground, seen and touched for the first time in centuries.

“Finding artifacts is absolutely amazing in a way that I truly did not expect. I thought we’d be digging around in the ground, and pull up some metal and, sure it’d be cool, for a moment. But the reality is so different and spectacular,” says Wyatt. “I don’t know if there’s a spirit to the object or what, but you pull it out of the ground, and you have an instant connection to that object. It’s telling you a story; it’s now part of all our stories as Americans. I’ve heard people cheering — a whole transect area cheering — because they just found something.”

What AVAR gives to its participants is obvious. But what does it contribute to the broader field of archaeology? Simply put, an unparalleled work ethic that drastically increases an expedition’s efficiency and output.

“I don’t know how to say it without sounding derogatory towards civilians, and I don’t want to do that,” says Reed. “But when you get a group of veterans together who have done the hard grunt work — 5 o’clock in the morning until 4 o’clock the next morning — thrown together, all of a sudden, everything is getting done without even being asked.”

Beyond the perseverance and tenacity created by serving in uniform, participant Greg Ashcroft, a medically separated Army specialist from Utah, muses that the military connection to soldiers of the past is also a driving force. “We feel a responsibility to put our best effort toward what we’re doing. So that we can accomplish the mission and find all the artifacts. Then the story can be told accurately and we have it for posterity.”

Regardless of why, the results are evident. “This was just a great partnership,” says NPS archaeologist Griswold. “Working with AVAR really allows us to extend our available dollars and undertake a much bigger project than we had originally planned. We’re getting far more information out here then we would have been able to if we would have had to contract out the project, or just handle it locally… So it’s a win-win-win-win all around.”

Not only did the participation of the AVAR team mean more ground was covered in 2019 than had been anticipated, but the resounding success has paved the way for future partnerships. NPS almost immediately expressed interest in a second phase at Saratoga, potentially in 2020, as well as other future efforts. The American Battlefield Trust stands ready to continue its commitment to facilitating this important work.

Related Battles

330

1,135