Digging Down Deep: The Emotional Significance of Archaeology With Veterans

Archaeology bonds veterans because it is a lot like military service. In a sense, it’s like the military without the shooting. We have a shared mission that requires us to pull together under the guidance of a technical specialist. We work outside, with our hands and on a tight schedule. We stand alongside other veterans with shared values. Plus, there’s that sense of adventure, which — aside from the fact that they are patriotic individuals — is a major reason people join the military.

Veterans need transitional programs like AVAR because civilian and military culture are very different. Our program puts former military personnel in a new kind of trench, together with civilians, in pursuit of a common cause. The veterans receive training to pursue a civilian job for which they are predisposed to be well-equipped, already possessing a solid working knowledge of maps, which is a core skill in archaeology. Thus, they see that skills gained in the military are still relevant, even if they are unlikely to be called upon to fire a machine gun again. With archaeology, they see a tangible example of their skills being useful and relevant. Veterans need this because it shows them they can still accomplish incredible things even though they’re no longer wearing the uniform.

But this is more than a work training program. We don’t gauge success by whether or not participants become archaeologists; we gauge success on whether or not they become more productive, more able to reach their goals. We want them to be happier and less isolated when they leave. AVAR offers veterans a way to interact and form incredible bonds working and sweating in the field together. In the evenings, they relax and they start opening up. A lot of these folks may be on disability, not working very much. Civilians don’t understand them, and they’re keeping everything inside. But by working together, living together, they engage in what we call peer-to-peer support therapy.

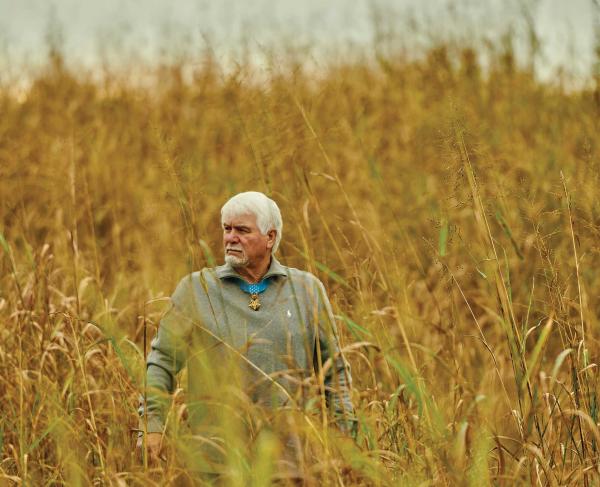

Many veterans need some type of therapy when they come back because they see horrendous things when they go off to war in Iraq or Afghanistan. Things that people back home don’t understand. Veteran culture itself keeps them from talking, but many have conditions that compound this tendency. Post traumatic stress disorder is one that you hear about a fair amount, but traumatic brain injury is also common among our participants. Someone who doesn’t have these conditions really doesn’t understand what they feel like — how they isolate you and impact your life and your family. These people have gone from being incredibly capable, tip-of-the-spear individuals, to being labeled as disabled individuals. Together, we show they can do incredible things despite having a disability rating, or despite having these labels. We prove to them that other people have these same conditions and experiences: “I deal with that, too. My spouse hates how I wake up in the middle of the night. My kids feel distant from me since I’ve come home.” They have a new fight, in a sense — against the conditions that plague them after service, and it’s much easier for them to fight as a group.

We absolutely strive to create a safe environment in all AVAR programs. We have a mental health adviser, a licensed master of social work and clinical dependency councilor, who assesses all the applications and is on-site the first week of a project, making sure everything is going to work for the veterans.

AVAR is committed to putting veterans on the battlefield because that is home turf for them, a place onto which they can project their own experiences. We are very intentional and respectful in how we proceed, striving to gather data without digging up and destroying the battlefield. In a real sense, these veterans are still protecting a battlefield at home, just like they would in the Middle East.

There is no way to put into words the experience of watching another veteran find something for the first time, because you see that flicker come back on in their eyes again. For a lot of these guys, going on an archaeology dig is the experience of a lifetime. They’ve watched Indiana Jones and television documentaries, but this is something they never thought they could do. They go from sitting on a couch for too long or having a job they don’t particularly enjoy — nothing compared to the adrenaline and stress of what they were doing when they were in uniform — to holding something in their hands that nobody has touched for 250 years, when it was in some way important to a different soldier.

I’ve learned that it’s really difficult to help people. There’s no formula that tells you how to go about taking someone from point A to point B. Instead, it all comes down to compassion. We try to integrate compassion into every aspect of what we do. We put the best interests of each individual above process and procedure. We only want each person to have an enjoyable experience. More than that, it’s about that one person moving forward and being able to do something different and better with their life when they leave. If you care about your brother the way you did when you were in uniform, everything else falls into place.