No British army in history had ever surrendered. Trapped on the hills overlooking the Hudson River, surrounded and running short of supplies, Lieutenant General John Burgoyne contemplated the impossible.

There were hundreds of battles, skirmishes and sieges fought during the American War for Independence (1775–1783), and the sites of many are preserved as private, state and national historic sites, parks or monuments. A more limited number were decisively significant to the American Revolutionary cause — the opening shots at Lexington and Concord, the Christmas crossing of the Delaware and surprise attack at Trenton, George Washington’s personal charge at Princeton, the double-envelopment of British forces at Cowpens, Cornwallis’s surrender at Yorktown.

And yet, the Battles of Saratoga have long held special distinction among the panoply of famed battles — the phrase “Turning Point of the Revolutionary War” was coined for Saratoga. But their significance stretches even further, into the scope and breadth of worldwide warfare as well. How could two battles fought in rural upstate New York in the fall of 1777 possibly rate so importantly?

In June 1777, a British army stationed in Canada commanded by Lieutenant-General John Burgoyne began an expedition intent on capturing Albany, N.Y. Once taken, Albany would serve as a staging ground from which the British could thereafter threaten New England or the lower Hudson River Valley, creating a potentially insurmountable rift between regions of the new nation. An earlier iteration of the plan called for the main British Army, located in the City of New York, to move north and assist Burgoyne, but British priorities changed and the main army was destined to capture Philadelphia instead. Burgoyne was aware of this fact before he began his campaign, and was not deterred by the King's approval of these two divergent plans.

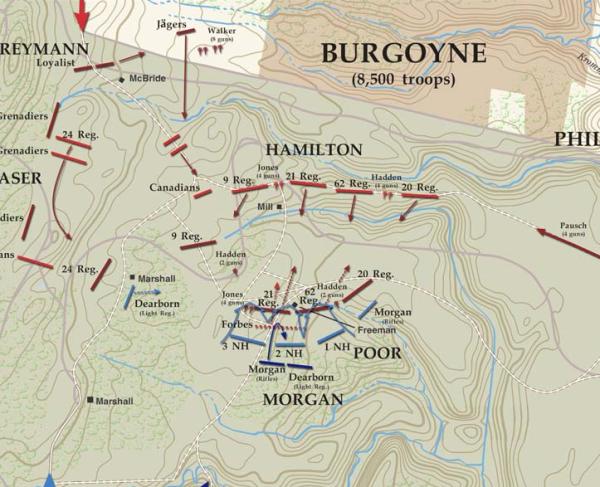

After months of campaigning, featuring relative triumphs for each side — the virtually bloodless British recapture of Fort Ticonderoga set against the conclusive American victory in the Battle of Bennington — the American and British armies finally met in earnest battle about 40 miles north of Albany on September 19, 1777. The Battle of Freeman’s Farm came about when riflemen under Colonel Daniel Morgan and a contingent of light infantry led a reconnaissance in force from the American lines, which the British threatened to flank. Ultimately, Burgoyne’s troops carried the field, but at a loss of 600 men — a roughly 10 percent casualty rate that exacerbated the steady attrition of his forces from desertion and lack of supplies. Receiving word that British troops were finally heading north from New York to assist him, Burgoyne chose to dig in and wait. Those reinforcements never materialized, having turned back south of Albany.

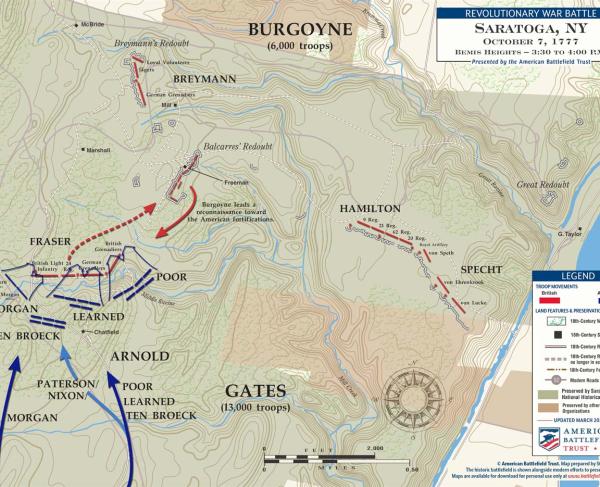

Two and a half weeks later, the armies clashed again in the October 7 Battle of Bemus Heights (alternately rendered as Bemis Heights). Buoyed by militia units from across the region and 2,000 more militia under General Benjamin Lincoln recalled from an excursion against Ticonderoga, the American ranks had swollen during the interim. The British, meanwhile, had been surviving on reduced rations for a fortnight.

Amidst a British reconnaissance in force, the Americans counterattacked across the Barber Wheatfield, clashing at the Balcarres Redoubt and Breymann's fortified camp. American Major General Benedict Arnold, who planned this decisive attack against the British reconnaissance, was famously wounded in the left leg while leading victorious Americans against the latter.

In truth, the Battles of Saratoga themselves — the collective designation for the Battle of Freeman’s Farm and the Battle of Bemus Heights — were not war winning. The first was a strategic win but a tactical loss for the cause of independence. And, while the second was a decisive victory, others, including Bennington, Vt., and Kings Mountain, S.C., were even more so. But because military victories are often measured by their political consequences — warfare is, after all, usually a manifestation of political designs — the Battles of Saratoga were second to none.

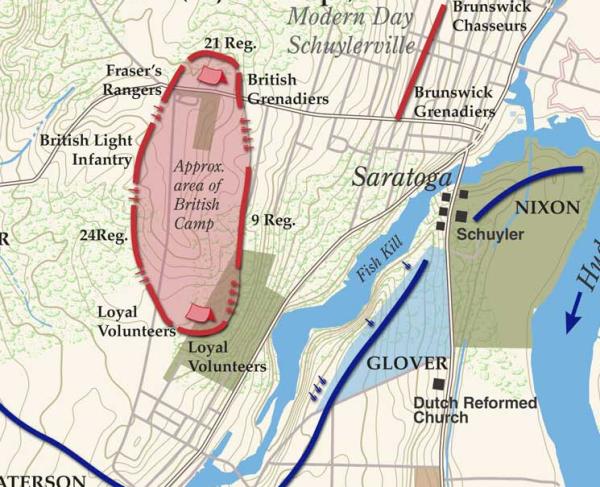

Having lost the Battle of Bemus Heights, Burgoyne retreated north about eight miles to a hamlet then called Saratoga — now known as the Village of Schuylerville — and hunkered down in strangely apathetic fashion. This nonchalance allowed the American army to pursue, surround and besiege Burgoyne, forcing him to send a flag of truce and enter into negotiations with the Americans who, by then, outnumbered him nearly three-to-one. After days of negotiations, Burgoyne surrendered his army of nearly 7,000 to Gates on October 17, 1777.

The ramifications were immediate and far-reaching. Burgoyne did not simply surrender a British army — he surrendered the first British army in world history. The removal of this army simultaneously quashed British plans to conquer upstate New York and freed up thousands of Continental troops so they could be redeployed to join Washington’s forces near Philadelphia, placing most in winter quarters at Valley Forge. After a string of demoralizing defeats in 1776 and 1777, this victory inspired, encouraged and motivated America’s depressed and despondent forces. The resounding battlefield defeat of a British army was, in fact, possible.

Just as significant, the impact stretched well beyond American shores. Gates’s victory over Burgoyne was the primary impetus King Louis XVI needed to recognize the independence of the United States of America, making France the first world power to do so. Further, the ancien régime joined the United States in a formal military and commercial alliance. French aid, in the form of arms, camp equipage, ammunition, money and clothing, as well as French army and naval support, were essential for U.S. victory in the war. This was particularly manifested at Yorktown, Va. The French Navy closed Chesapeake Bay as a route of resupply and relief, allowing French engineers and artillerists to orchestrate an impressive allied siege and bombardment. Ultimately, the world turned upside down, and the second British army in world history was “Burgoyned” as Cornwallis surrendered his entire field command on October 19, 1781.

As if this were not enough, Great Britain could no longer afford to focus on the conflict in America alone, since French entry into the war resulted in fighting over colonial possessions on a global scale. French-allied Spain declared war on Britain in 1779 and the Netherlands went to war with Britain in 1780. Battles on land and sea were fought in places as far-flung as modern-day Florida, the Mississippi River Basin, the Caribbean, the Bahamas, Nicaragua, Guyana, the Channel Islands, Gibraltar, Senegal, Ghana, the Gambia and Sri Lanka. The French-allied Kingdom of Mysore (in modern India) declared war against the British too, resulting in major fighting throughout India’s southern interior in 1780–1784.

Great Britain was overwhelmed with enemies the world over. The diffusion of its forces to protect and strike at colonial possessions was too great a strain to sustain. Needing to extricate itself from the scenario of no-win global warfare, Great Britain agreed to make peace with the newly recognized United States in 1783. American victory over the British was made possible by the French alliance — and Saratoga had made that alli-ance possible.

The success of the American war for independence in turn inspired colonial uprisings around the globe and enshrined representative democracy as the dominant political philosophy of the entire Western Hemisphere. For this reason, R. W. Apple, chief correspondent for the New York Times Magazine’s “Best of” Millennium Edition in 1999, deemed Saratoga “the most important battle ever fought in the world within the last 1,000 years.”