The French and Indian War (1754-1763) was fought between Britain, France, and their respective Native American allies for the control of North America. In the 18th century, no major road networks existed that connected the British and French colonies. Waterways like lakes and rivers served as the main routes of invasion and supply for opposing armies. The most efficient way to defend these avenues was by building strong forts of timber or stone. Whoever controlled the waterways, in the end, controlled the continent, and because of this, the battles of the French and Indian War were almost entirely fought to capture and defend fortifications in these areas.

In the 18th century, both British and French forts shared a very similar design influenced by the work of Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban, a French military engineer. A veteran of 48 siege operations during the 17th century, Vauban was an expert at conducting them and defending against them. His star-shaped fort designs, with four or more bastions (protruding points that allowed the defenders to fire from multiple angles creating a crossfire), were used by both sides in North America. Vauban understood that it was inevitable that a fort would eventually fall if besieged long enough. His philosophy was to erect a strong enough fort of stone with outer walls and defensive works that could hold off long enough against enemy cannon in order to tire out the besieger, forcing him to end the operation. Both British and French engineers during the French and Indian War did not have the luxury of building such massive installations because of the geography, available resources, and little construction time available to them. It was necessary for them to adapt, in most cases being forced to erect much weaker, wooden forts that could not withstand an enemy with superior firepower.

The five major theaters of the French and Indian War were the Ohio River Valley, Hudson River–Lake George–Lake Champlain Corridor, Great Lakes Region, Nova Scotia, and Canada. It was here that the opposing engineers constructed new and repaired already existing fortifications to defend the waterways and created forward bases to launch attacks against the enemy. The following text will highlight the major forts and their roles played during the war.

Ohio River Valley

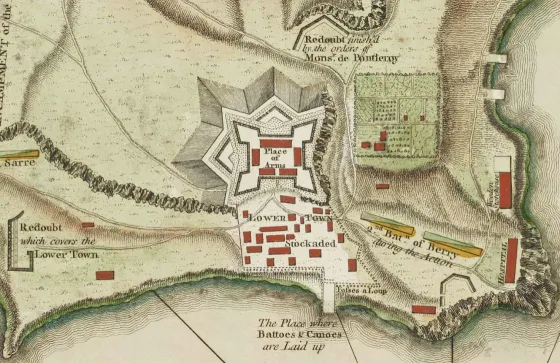

The Ohio River Valley was the match that lit the continent, and the world, on fire. Control of the Forks of the Ohio River (present-day Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania), where the Allegheny, Monongahela, and Ohio Rivers converged, was indispensable. In the 18th century, France’s holdings extended in a wide arc from the Gulf of Saint Lawrence, through the Saint Lawrence River, the Great Lakes, the Illinois country, and down the Mississippi River all the way to the Gulf of Mexico. The Ohio River’s mouth was at the Mississippi River, and therefore, the Forks needed to be held in order to keep communications open with the French troops and settlers around Louisiana.

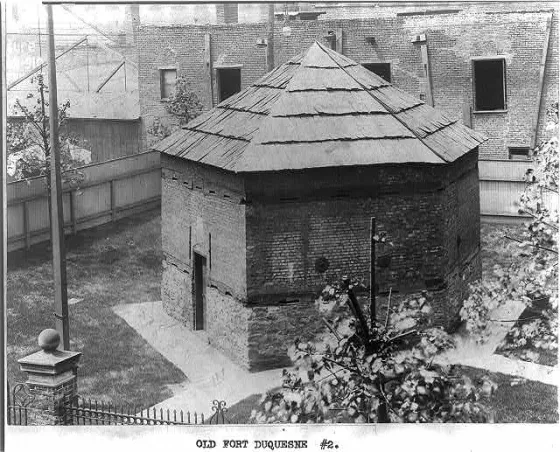

In 1754, French forces erected Fort Duquesne at this crucial confluence, and it became the focal point of Britain’s military efforts in the region. The first major attempt to capture it occurred in July 1755, when a British force under the command of Major General Edward Braddock fought a battle along the Monongahela River, several miles outside the fort’s walls, with Canadians and their Native American allies. It was a disaster for the British, costing them over 900 men killed, wounded, and captured.

For the next three years the fort faced no serious threats until another British army, led by John Forbes, entered the region. Braddock’s Defeat forced Britain to adapt to the military situation in western Pennsylvania and begin constructing lines of fortifications to be used as supply bases and jumping-off points for future campaigns. Fortifications like Fort Frederick (Big Pool, Maryland) and Fort Loudoun (Winchester, Virginia) were built to deter and defend against French and Native American raids along the frontier, but could also be used as forward bases for troops and supplies. General Forbes went even further in Pennsylvania. Along his route from Carlisle to the Forks, he hastily constructed forts, like Fort Ligonier (Ligonier, Pennsylvania) every 40 or 50 miles to ensure his supply line was not stretched too thin, and to have defensive positions to fall back upon should he be forced to retreat. As his army approached Fort Duquesne in November 1758, developments in the Great Lakes Region, which served as the gateway to the Ohio River Valley, forced the French to blow the fort up and retreat north.

Great Lakes Region

Lake Ontario was the most important of the Great Lakes for the French, because the Saint Lawrence River ran into it from the northeast. At the southern end, the Niagara River traveled south into Lake Erie, and from there, a direct route overland led to the Forks. The French in North America had already constructed fortifications in the 17th century at the two points where Lake Ontario met the two rivers, giving them the upper hand at the outbreak of hostilities. Fort Frontenac guarded the Saint Lawrence entrance, and Fort Niagara, the Niagara River side. Both were permanent stone structures.

In 1755, at the same time, Braddock was moving against Fort Duquesne, another British and colonial force was moving against Fort Niagara. Before an attack could be launched, however, an old trading post at the southeastern end of the lake, where the Oswego River entered, needed to be repaired. Fort Oswego and Ontario were a combination of stone and wood structures on both sides of the river. No attack against Fort Niagara manifested that year, but in August 1756, a French force under the Marquis de Montcalm struck the British to drive them from the lake. After holding out for several days, the Forts’ garrisons surrendered. The forts were too badly damaged by French artillery during the siege and were abandoned and later destroyed. Montcalm left men at Niagara and Frontenac and moved the rest of his force to Fort Carillon, which had been completed earlier that year at the northern end of Lake George in Upstate New York.

Like in the Ohio River Valley, no major British attempts were made to capture the French forts along Lake Ontario until 1758 and 1759. In August 1758, an entirely provincial force (British colonists) besieged Fort Frontenac and captured it. The loss of the fort severed one of France’s lines of communication and supply into Lake Ontario, and subsequently the Ohio River Valley. It was also a blow to French prestige in the region in the eyes of the Native Americans. The next year, Fort Niagara fell as well, giving the British control of the lake. New France was being squeezed from all sides day by day.

Hudson River–Lake George–Lake Champlain Corridor

The Hudson River–Lake George–Lake Champlain corridor was one of the most contested regions on the continent. For both sides, it was a direct invasion route into the British colonies and Canada as well. The Hudson, which flows into the Atlantic passed New York City, traveled north beyond Albany, where a portage and water route led to Lake George, then into Lake Champlain, the Richelieu River, and then into the Saint Lawrence towards Montreal and Quebec. In September 1755, a battle was fought at the southern edge of Lake George. The French were beaten back and sent retreating to the northern end of the lake, where construction of the stoned Fort Carillon (Ticonderoga) commenced and was finished the following year. Ten miles to the north on the western shore of Lake Champlain, the pre-war and stone-made Fort St. Frederic was also held by the French. The ground won by the British during the Battle of Lake George was used to build the timber Fort William Henry on. These were all Vauban-style bastioned forts.

In 1757, Fort William Henry was besieged by an 8,000-man army under the command of the Marquis de Montcalm. It was a prototypical European-style siege, with trenches, cannon, and mortars begin dug and placed closer to the fort every day. The log exterior of the fort could not withstand the firepower of the French guns, and after a week it surrendered and was razed by Montcalm. He returned with his army to Carillon, and the British returned to occupy the same ground. The next year, a massive British army moved by boat up Lake George to take Fort Carillon. No siege occurred, however. Montcalm preferred to fight outside the walls of his forts behind earthworks if he was outnumbered. Wave after wave of British soldiers attacked his defensive lines, suffering over 2,000 casualties. The British had failed but returned in 1759 with an army led by Sir Jeffry Amherst. Like at Fort Duquesne, the French blew up the fort the best they could and retreated north into Canada. Fort Saint Frederic was captured next, and subsequently repaired. These same forts would play a significant role in the Revolutionary War, defending against another British invasion, not from the south, but from Canada.

Nova Scotia (Acadia)

Although Nova Scotia had been ceded by France to the British following the War of Spanish Succession (1701-1714), the French still held influence over a large portion of its inhabitants and controlled Fortress Louisbourg, a fortified settlement with massive stonewalls protecting its boundaries, on Cape Breton Island. Louisbourg was significant because it controlled the entrance into the Gulf of Saint Lawrence and the river itself, defending against invasion and keeping open the major supply and reinforcement route.

In 1755, as the British were moving against Fort Duquesne, Fort Niagara, and Lake George and Lake Champlain, another force was working to take two forts along the Chignecto Isthmus, Beauséjour and Gaspereau, in the heavily French-influenced region of Acadia along the Bay of Fundy. The two garrisons surrendered (Gaspereau without even a shot in anger being fired), and British control of the region was secure. A massive ethnic cleansing effort commenced, and thousands of Acadians were shipped off in exile.

Even after the fall of Acadia, Fortress Louisbourg still stood in French hands on Cape Breton Island. An attempt to capture it was aborted in 1757, but the British returned in full force the next year in early June with nearly 14,000 men and 40 warships. After a combined land a naval siege, the fortress fell on July 26. The gateway to Canada was open.

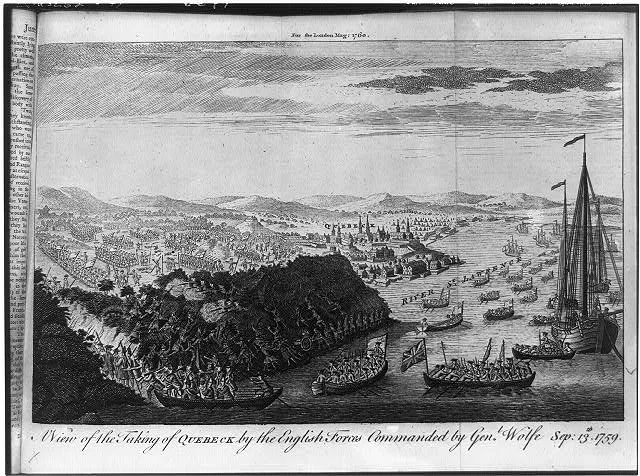

Canada

Because of the successes of the British Army in the previous years in capturing the French forts that commanded the invasion and supply routes, New France had been squeezed into an area comprised of the regions around Quebec, Trois-Rivières, and Montreal. There was not much left to do for the French army, commanded by Montcalm, but to sit back within the fortified cities of Quebec and Montreal and their outer defenses for British failure or for friendly reinforcements to arrive. James Wolfe, whose army besieged Quebec in June 1759, hoped to lure Montcalm out of his defenses into an open field battle so he could use his professional British regulars to his advantage against the French general. Montcalm obliged, and on September 13, the decisive battle of the war was fought on the Plains of Abraham in a field west of the city’s walls. The British were victorious in just fifteen minutes. Wolfe was mortally wounded and died a hero on the field. Montcalm, too, was hit by grapeshot in the abdomen and died the next morning. Five days later, Quebec surrendered. The French retreated further downstream to Montreal, attacked and failed to retake Quebec the next spring, and surrendered in whole on September 8, 1760, effectively ending all major military operations in North America during the French and Indian War. The battle for the continent between Britain and France was over. The fate of the forts along the frontier, lakes, and rivers of the continent decided the conflict, and many of the same fortifications served Patriot and British forces alike in the next war—the war for American independence.