The American Civil War ended in 1865, closing a momentous chapter in the history of the United States. Both the individuals and the institutions involved in the conflict were left forever altered. For all the men who fought — officers and enlisted alike — the war loomed large in their experience, later influencing the formative years of their children and grandchildren.

Returning home from the front, many veterans went on to achieve success in a variety of fields. Others chose to remain affiliated with — or eventually return to — the military. Thus, while for some leaders the Civil War was the culmination of their careers, for others, it was only a first stage in a long career.

Frontier Fighters

Most Civil War veterans who stayed in the U.S. Army spent time on the frontier fighting in the various Indian Wars from 1862 to 1890. For most of this period, direction and policy for these conflicts came from high-profile Civil War figures William T. Sherman, stationed in St. Louis, and Philip H. Sheridan, stationed in Chicago. In fact, Civil War veterans served as Commanding General of the U.S. Army continuously until 1903: U.S. Grant (1864–1869), Sherman (1869–1883), Sheridan (1883–1888), John M. Schofield (1888–1895) and Nelson A. Miles (1895–1903). The former four commanded armies in the Civil War, while Miles was a regimental, brigade and division commander in the Army of the Potomac.

Additionally, Civil War army commanders George H. Thomas, E.O.C. Ord, John Pope, Irvin McDowell, Oliver O. Howard and E.R.S. Canby also commanded departments and played important roles in the Plains conflicts, as did former corps commander Alexander McCook. Canby was assassinated in 1873 on a peace mission, while Howard directed the chase of the Nez Perce four years later.

Civil War veterans figured prominently in two of the most important battles of the period: Little Bighorn in 1876 and Wounded Knee in 1890. All of the senior commanders of the Little Bighorn campaign — Alfred H. Terry, George Crook and John Gibbon — commanded large formations during the Civil War: Terry captured Fort Fisher, N.C., in 1865; Crook commanded a corps in the 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign; and Gibbon’s men faced Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg. In the 7th Cavalry, Lt. Col. George A. Custer — commanding in the absence of the regiment’s colonel, former Civil War general Samuel D. Sturgis — and all officers down to captain had served in the war, several with distinction.

At Wounded Knee, the 7th Cavalry was led by James W. Forsyth, Sheridan’s chief of staff in the 1864 Valley Campaign and through the actions at Petersburg and Appomattox in 1865. He acted on orders from Miles, his superior based in Rapid City, S.D., and Schofield in Washington, D.C.

Beyond the Battlefield

In addition to fighting on the frontier, Civil War veterans used their experiences to develop the U.S. Army of the next generation. In 1870, Sheridan, William B. Hazen and Forsyth went to Europe to observe the Franco-Prussian War. All three men came away impressed; Sheridan, in particular, wrote a detailed account of the conflict in his memoirs. Army of the Potomac veteran Emory Upton stands out among military thinkers and writers of this period, penning several influential articles and a posthumously published book on military policy.

A succession of Civil War veterans served as superintendent of West Point from 1864 to 1898, among them former Union generals Thomas H. Ruger, John M. Schofield, Wesley Merritt, Oliver O. Howard and John G. Parke. Among those who benefited from their leadership during these years were John J. Pershing and the senior leaders of the World War I American Expeditionary Force. Scott Shipp, who commanded the Virginia Military Institute (VMI) Corps of Cadets at the Battle of New Market in 1864, served as VMI’s superintendent from 1890 to 1907 — the only Civil War veteran to hold that post. Among his students were George S. Patton, Jr. (1904, transferred to West Point) and George C. Marshall (class of 1901).

Meanwhile, Oliver O. Howard led the Freedmen’s Bureau after the war and established Howard University in Washington as a place for educating freed slaves. The school is still going strong nearly 150 years later.

Yellowstone National Park came into being in 1872, and in 1886 Sheridan placed it under the care and control of the U.S. Army, an arrangement that lasted until 1918.

In 1896, Alexander McCook, a former corps commander in the Army of the Cumberland in 1862–1863, represented the United States at the coronation of Czar Nicholas II.

Servants of the Khendive

During the 1870s some Civil War veterans took commissions in the Egyptian Army after the Khedive — the self-proclaimed title of the regional vassal government — gained a measure of independence from the Turkish Empire. Former Confederate generals Raleigh E. Colston, Charles W. Field, William W. Loring and Henry H. Sibley all became senior leaders and administrators of the Khedive’s army. Colston and Field had previously led divisions in Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, while Loring held a like command at Vicksburg. Sibley commanded in Texas and led an unsuccessful invasion of New Mexico in 1862.

Meanwhile, former Union Brig. Gen. Charles P. Stone, who had been disgraced after the 1861 defeat at Ball’s Bluff, rose to the top of the Egyptian service, becoming the Khedive’s chief of staff and aide from 1870 to 1883.

Although not prominent in the Civil War, Marylander Charles Chaille-Long — a veteran of Gettysburg with the 1st Maryland Eastern Shore — served in the Egyptian Army as a lieutenant colonel. Although not prominent in the Civil War, Marylander Charles Chaille-Long — a veteran of Gettysburg with the 1st Maryland Potomac Home Brigade — served in the Egyptian Army as a lieutenant colonel. He explored the Upper Nile (modern Uganda), was one of the first westerners to see Lake Victoria and served as aide to British general Charles “Chinese” Gordon from 1874 to 1877. Chaille-Long’s book about his service with Gordon is a vivid but controversial account of that period.

Fighting Spain

Many of the Civil War’s junior officers had risen to become senior officers by the time of the 1898 War with Spain and the 1899–1902 Philippine War. This was a three-front war, involving land operations in Cuba, Puerto Rico and the Philippines. Many U.S. forces trained at Chickamauga Battlefield Park before deploying.

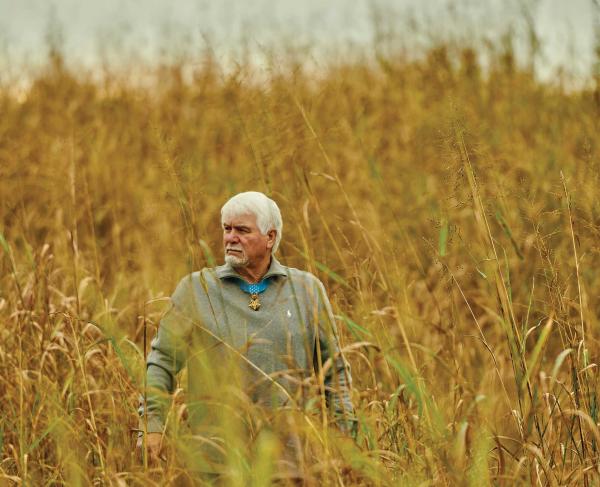

In Cuba, the main U.S. force was the V Corps under William R. Shafter, a Medal of Honor recipient from the Battle of Seven Pines and a veteran of battles in the Civil War’s Eastern and Western Theaters. Shafter’s troops besieged the port of Santiago, capturing San Juan Hill and other key sites in a series of attacks that forced the city’s surrender.

Puerto Rico fell in a lightning campaign to 15,000 men under the overall command of General Miles. The bulk of this force was the U.S. I Corps under John R. Brooke, a former Army of the Potomac brigade commander.

In the Philippines, Wesley Merritt’s VIII Corps captured Manila with the help of Filipino guerrillas. One of Merritt’s division commanders was Arthur MacArthur, who had earned the Medal of Honor at age 18 for leadership under fire in the Battle of Missionary Ridge outside Chattanooga.

Two Confederate generals returned to U.S. service for this war — Major Generals Fitzhugh Lee and Joseph Wheeler, although Lee did not deploy overseas. Wheeler fought in Cuba under Shafter, at one point exclaiming that “We got the Yankees on the run!” in his passion after a victory over Spanish troops.

Afloat, the most prominent Civil War veteran of this new conflict was Adm. George Dewey, a veteran of New Orleans and Port Hudson, whose pivotal victory at Manila Bay broke Spanish naval power in the Pacific. Civil War naval veterans William T. Sampson — who had served along the South Carolina coast — and Winfield Scott Schley — who saw considerable action along the Mississippi River — were both counted as heroes of the Santiago Campaign in 1898, but controversial dispatches from the engagement obscured the exact role each man played.

Military Dynasties

Deeper into the 20th century, family connections to the Civil War inspired and sustained several prominent soldiers of World War II.

Edward P. King was the son-in-law of Lafayette McLaws, a division commander in Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia in 1862–1863. A Georgian, King grew up around Confederate veterans who inspired him to become a soldier. In 1942, King commanded the 76,000 Americans and Filipinos on the Bataan Peninsula in the Philippines. Repeated Japanese attacks defeated his starving and exhausted troops, and King surrendered his command on April 9, 1942, precisely 77 years after Lee laid down his arms at Appomattox. King described his feelings before capitulating as akin to Lee’s, even invoking part of Lee’s famous quote from 1865: “I go to meet the enemy commander, and I would rather die a thousand deaths.”

King’s superior on Corregidor, Jonathan M. Wainwright, IV, also drew inspiration from his Civil War ancestors. His paternal grandfather commanded the USS Harriet Lane during the taking of New Orleans in 1862 and died during the Battle of Galveston in January 1863; his maternal grandfather Edward Serrell designed the famous Swamp Angel cannon at Charleston and served as chief of staff of the Army of the James in 1864 and 1865. Inspired by their examples of service and duty, he soldiered through the surrender of the Philippines in May 1942 and three years as America’s highest-ranking prisoner of war.

George S. Patton, Jr., had a grandfather and seven other ancestors in the Confederate army. His grandfather was mortally wounded at the Third Battle of Winchester in 1864 and is buried in Winchester next to a brother who had died commanding the 7th Virginia during Pickett’s Charge. General Patton grew up in California and learned how to ride a horse using the saddle on which his grandfather suffered his mortal wound. Patton played with his grandfather’s sword and, as a child, listened to stories of the Civil War told by legendary “Gray Ghost” John S. Mosby. These examples drove Patton to be a soldier and a leader — and one of the iconic generals in U.S. history.

Douglas MacArthur was the youngest son of Arthur MacArthur, Jr., who, after his actions at Missionary Ridge, went on to see additional service in the Indian, Spanish-American and Philippine-American wars. Young Douglas also had three maternal uncles from Norfolk in the 6th Virginia, and a cousin of his mother fought with the VMI Corps of Cadets at the Battle of New Market. These ties led Douglas to refer to himself as “the reunion of blue and gray personified.” The example of his family, especially that of his father, set the course for Douglas’ life — West Point, service in Asia, leadership in both World Wars, governance of Japan and a United Nations post in the Korean War. Arthur and Douglas became the first father-son pairing to earn the Medal of Honor. General MacArthur’s connection to Norfolk led him to choose that city as the site of his grave and museum/archive, which is today known as the MacArthur Memorial.

The U.S. Army

Individual Civil War veterans left a tremendous military legacy after the war, but the conflict also changed the fabric and structure of the U.S. Army in ways still visible today.

After every war it has fought, the U.S. Army underwent major transformation and reduction in strength. In May 1865, the United States had just over a million men in the Army, of which 800,000 volunteers had been mustered out by the end of the year. The remaining volunteers, including a significant number of United States Colored Troops, stayed in service until the official proclamation of peace on August 20, 1866. By 1867, virtually no U.S. Volunteers enlisted during the years 1861 to 1865 were still on active duty.

Regular Army units from the Civil War continue to exist within the U.S. Army today, albeit with a host of battle honors added during American conflicts from the past 150 years. Most famously, the 3rd Infantry — the “Old Guard” — is the ceremonial detail for Arlington National Cemetery and provides guards for the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. The 1st Infantry Division combines the Civil War-era 16th and 18th Infantry Regiments with the postwar 26th Infantry, which means the division has carried battle honors of the Army of the Potomac and Army of the Cumberland to places like the Argonne, North Africa, Sicily, Normandy, the Ardennes, Vietnam and the Persian Gulf. The 5th Cavalry, famed for its charge at Gaines’ Mill in 1862, has been an integral part of the 1st Cavalry Division since World War II, seeing action in New Guinea, the Philippines, Vietnam (including the Ia Drang Valley in 1965) and Iraq. Several units, like the 13th Infantry — “First at Vicksburg” — and 19th Infantry — “Rock of Chickamauga” — have incorporated their Civil War heritage into their modern identities.

In the wake of the Civil War, the Regular Army escaped postwar reductions for the only time in U.S. history. The Army expanded from its 1861 strength of 15,000 men to 57,000 in 1869, although the latter figure was later reduced, in stages, to 27,000. This expansion added the 7th and 8th Cavalry Regiments, and infantry regiments numbered 20 through 49, although many infantry units underwent significant reorganization and reduction in the 1870s. An important part of the Army’s postwar expansion was the 1866 addition of the 9th and 10th Cavalry Regiments (later the famed “Buffalo Soldiers”) and 24th and 25th Infantry Regiments, comprised of African American soldiers officered by whites.

Former Confederates remained shut out of the U.S. Army, but many Confederate veterans helped re-create state militias in the 1870s and 1880s. These units, which drew their lineages and designations from famous Confederate formations, were absorbed by the Army National Guard in the early 20th century. As part of the Guard, the militias saw service in subsequent American conflicts and remain until the present day. Famous examples — with their official, Civil War-inspired nicknames — include Virginia’s 116th Infantry Regiment (Stonewall Brigade), Alabama’s 167th Infantry Regiment (4th Alabama), Louisiana’s 141st Field Artillery (Washington Artillery), Kentucky’s 623rd Field Artillery Regiment (Morgan’s Men) and North Carolina’s 120th Infantry Regiment (3rd North Carolina).

Northern state militias also drew lineage from Civil War volunteer units, and veterans, like Medal of Honor recipient Frederick Phisterer in New York, helped lead state forces in the late 19th century. These formations are also now part of the Army National Guard, and like their Southern counterparts, they carry battle honors from later wars. Examples — with official nicknames — include New York’s 106th Infantry Regiment (14th Brooklyn) and 165th Infantry Regiment (Fighting 69th), Wisconsin’s 127th Infantry Regiment (1st Wisconsin), Maryland’s 175th Infantry Regiment (5th Maryland), New Jersey’s 102nd Cavalry Regiment (1st New Jersey), Maine’s 133rd Engineer Battalion (20th Maine), Kentucky’s 138th Field Artillery (Louisville Legion) and Vermont’s 86th Brigade (The Vermont Brigade).

The continuing legacy of the Civil War in the U.S. Army is perhaps best illustrated by the units that attacked the Normandy beaches on June 6, 1944. The U.S. 4th Infantry Division — with the Army of the Potomac’s 8th and 12th Infantry Regiments, joined by the postwar 22nd Infantry Regiment — assaulted Utah Beach. At Omaha Beach, the 1st Infantry Division’s 16th and 18th Infantry Regiments came ashore next to the 116th Infantry Regiment (Stonewall Brigade), supported by the 115th (descended from the Civil War-era 1st Maryland U.S.) and 175th (5th Maryland) Infantry Regiments from the 29th Infantry Division.

In 2015, there has been much discussion of legacies as the Civil War sesquicentennial draws to a close. The war affected the men who fought it and their families for generations, even changing the U.S. Army itself. These legacies echo to the present day in many cases and can be traced to and through most American battles and battlefields of the last century and a half. There is not space for more than a general survey of this vast topic, which has limited the number of people who could be included. Nonetheless, the military legacy of the Civil War lives on, long after the guns fell silent 150 years ago.