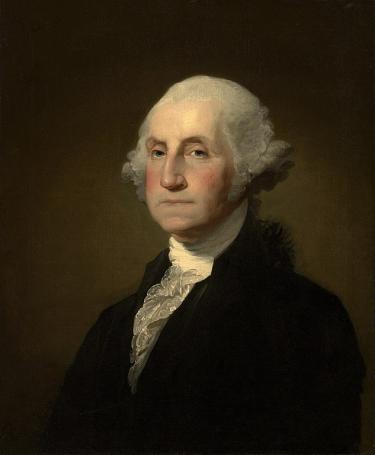

In his own time, George Washington was famous. The American Revolution would catapult the general into the stratosphere of the household names known around the world. Aside from Benjamin Franklin, it would be Washington who would become the most recognizable face to emerge in the earliest days of the United States. Unlike Franklin and others, Washington’s personal struggle with fame and public service can be found throughout his immense correspondence among contemporaries and in public addresses. This American was different from other generals and leaders that came before him. He almost seemed to dislike the responsibilities bestowed upon him. There is truth to this assertion. And it comes from Washington’s own study of history.

One of the more fascinating aspects of Washington’s personality is discovering who he considered his heroes. His father Augustus had died when the young George was a boy, so Washington looked up to his half-brother Lawrence as a father-figure. Lawrence’s service in the Virginia militia, rising to the rank of Major, impressed upon young George the nobilities in a military career. Tragically, Lawrence died of tuberculosis in 1752, leaving the twenty-year-old Washington without a role model it would seem.

Washington did not attend college, a fact that he remained insecure about for the rest of his life. He was literate and read extensively. By his early adult years, he had also taken to mastering a set of rules to live by. Copying an English translation of a French Jesuit creed, Washington’s Rules of Civility shows a strict forbearance on passions and letting one’s emotions get the better of themselves. A personal discipline devoted to restraint would become a central point of how he behaved in all manners of life. This reflected the wider influences of the Enlightenment.

One of the catalysts to the rapid change of political and cultural institutions in the Eighteenth Century was the profound effects the Enlightenment had on the Western Hemisphere. Logic and reason were considered noble tools to restrain emotion, which had been blamed for many of the problems of the past. By restraining one’s emotions, and using reason to solve problems, the path towards virtue could be achieved. Virtue had been a symbol among the early Greek states and was prized by Roman philosophers, chief among them Emperor Marcus Aurelius, whose stoicism would become influential once again during the Enlightenment. Stoicism is rooted in the suppression of emotion in order to achieve virtue. Washington was certainly a religious individual at many times in his life, but it can be viewed by his words and actions that his true religion was achieving virtue. And perhaps no Roman legend better served this image than that of Cincinnatus.

The story of Cincinnatus had been passed down for centuries. In modern film, we can see parts of his legend in the fictional Roman film, Gladiator, starring actor Russell Crowe as a wronged-general-turned-savior who fights the corruption in the capital. Lucius Cincinnatus was a Roman farmer who saved the Roman State twice from attempts by corrupt forces to rule over the people. Historians continue to debate whether the stories are true or fiction, but the consensus has been that Cincinnatus did voluntarily relinquish his power after becoming a dictator to return to his farm. The stories exemplified civic virtue or the act of being disinterested in public affairs. This belief would shield the public from corrupt leadership.

Another influence that shaped Washington and many of his officers in the Continental Army was the play, Cato. Based on the events of Cato the Younger, a Roman leader who defied Julius Caesar, the play’s themes of civic virtue, republicanism and liberty were seen as pillars that signified the reasons for fighting for American independence. The play was Washington’s favorite and he sat in attendance for it several times throughout his life. In 1778 at the Valley Forge encampment, Washington had the play acted out for the army, despite Congress barring such performances.

When we look at Washington’s actions and record as commander-in-chief of the Continental Army and then later as president, we see the strong influences these stories and beliefs hold on his thoughts. The public was already christening him the “Father of His Country” after victories at Dorchester Heights, Trenton, and Princeton, a phrase he sought to honor even if he continued to question if he was capable of living up to its expectations. Recall, Washington was reluctant to even accept command of the army in 1775. And among the near-impossible hardships he would face during the war: changing from an offensive strategy to a Fabian strategy of attrition, warring with both British and American generals through cult of personality, mustering up whoever was willing to fight for the Cause, supplying the army, and paying for it all; it is fairly obvious why Washington’s chestnut-colored hair turned fully gray in just eight years.

Of all the events that would come to define Washington as virtuous, none better exemplifies it as the two that occurred in 1783. After the Siege of Yorktown in October 1781 effectively ended the British Army’s campaign in North America, Washington still had to maintain the Continental Army while peace negotiations were being finalized in Paris. And it became increasingly difficult to hold the army together with no enemy to fight. To make matters worse, many in the army had not been paid for their service. At the time, the Confederation Congress had no authority to raise finances without calling on the individual states to pay their coffers. But states had been notoriously unreliable in doing so and by late 1782, there was talk of mutiny among officers in the American army. A handful of mutinies had been suppressed before. What made this one more dangerous was it was being instigated among the highest levels of the officer corps. In what would become known as the Newburgh Conspiracy, a meeting was called among the disgruntled officers on March 15, 1783, at the army headquarters in Newburgh, New York. As the meeting was set to begin, Washington unexpectedly showed up and delivered two speeches that effectively ended the planned mutiny. Had he failed, the officers would have marched the army to Philadelphia to hold Congress hostage unless their demands were met. It would have been a disastrous end to the American Revolution.

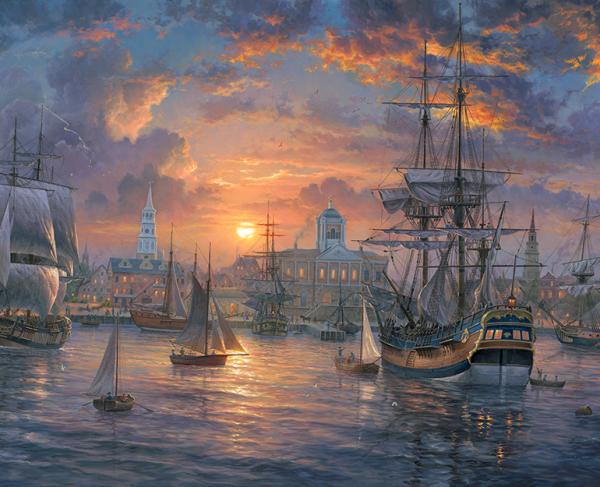

In December 1783, with the war now officially won, and American independence secured, Washington met Congress in Annapolis, Maryland. On the 23rd, he officially resigned his commission as commander-in-chief. In doing so, Washington was relinquishing power, signaling the army would be subservient to the elected body of Congress. This was the first instance in modern history where the triumphant military general did not become the de facto monarch of the country. His Cincinnatus moment had arrived and Washington lived up to it whole-heartedly. The decision shocked most around the world, particularly the monarchies in Europe who had no appetite for such acts of selfish resignation. Civilian rule had been firmly established in the United States thanks to George Washington’s actions in 1783.

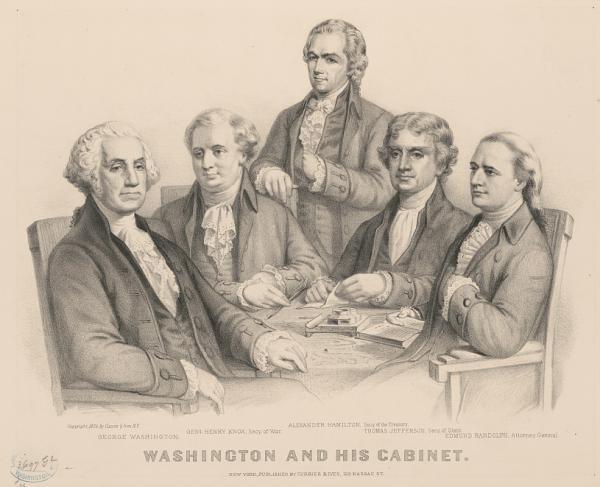

In retirement, Washington continued to present himself as the disinterested American hero. He had won the war and had achieved the highest possible virtue of handing power back to the people. As far as he was concerned, he had fulfilled his destiny and was determined to remain at his plantation, Mount Vernon. But public demands continued to find their way on his doorstep. Washington might have projected an aloofness to American politics, but his daily letters show him deeply involved and concerned over the trajectory of the country’s credit situation and expansion westward. Having stakes in both, and the contemptuous experiences with Congress during the war, Washington became a vocal critic of the Confederation. But when the Philadelphia Convention was assembling in May 1787 to propose changes to the Articles of Confederation, Washington was reluctant to attend. He had to be convinced that him, and only him, could give the body the legitimacy it needed to conduct the necessary changes to the government. He ended up presiding over the Convention and became a staunch supporter of the federal Constitution. Once again, he sought retirement, but was convinced that again, he and only he, could be the first president of the United States.

Washington’s reputation for virtue was the reason why he kept being called back into service to his country. Most leading politicians, like citizens, had wild opinions of each other, but all shared an affinity for Washington. There was a public trust rooted in his presence. He breadth confidence in the endeavor. He had survived Valley Forge and won the Revolution. He then gave up power only to be coaxed back into public service in order to strengthen the country (i.e. the federal government). It had to be Washington leading the new government. The faith of its competency rested on Washington steering the ship.

So it went for George Washington. Unanimously elected to the presidency in 1789, he would serve two terms before retiring again in 1797. His initial hopes of presiding over the presidency for just a few short months proved to be futile as several crises arose that demanded his leadership. He would remain popular as president, only facing criticism real criticism in his second term over tensions with France and Great Britain. But following his Farewell Address in 1796 and retirement the following year, the American Cincinnatus regained his stature as the singular example that most Americans could look towards with respect and fondness. He was the first American hero.

After his death in December 1799, Maj. Gen. “Light-Horse” Harry Lee eulogized him with the famous line, “First in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen.” The myth of Washington had long been established by the time of his death. The American Cincinnatus would become a legend himself with vast displays of revisionism and hero-worship throughout the Nineteenth Century that reinvented Washington as a deity. He was indeed just as mortal as the rest of us, despite his impressive good fortune under fire. The image Washington had carefully cultivated in his lifetime remains worthy of our interest if we are to better understand the man, not the legend. But to get to the man, we have to start with the legend of Cincinnatus.

Further Reading

- American Crisis: George Washington and the Dangerous Two Years After Yorktown, 1781-1783 By: William M. Fowler, Jr.

- The Return of George Washington, 1783-1789 By: Edward J. Larson

- Swords In Their Hands: George Washington and the Newburgh Conspiracy By: Dave Richards

- The Only Unavoidable Subject of Regret": George Washington, Slavery, and the Enslaved Community at Mount Vernon By: Mary V. Thompson

- Cincinnatus: George Washington & The Enlightenment By: Garry Wills