“First In Peace” George Washington During 1783-1789

On December 23, 1783, George Washington, the Commander-in-Chief of the victorious Continental Army accomplished perhaps his greatest achievement. On that day, Washington met with the Continental Congress in Annapolis, Maryland, and resigned his military commission and retired from public life. People were amazed that Washington, who was at the zenith of his power and had an army that was fiercely loyal to him, would voluntarily give up his position. Even King George III remarked that if Washington gave up his power, “he will be the greatest man in the world.”

Washington likely could have been made a king in America. One of his own officers in the Continental Army even suggested as much, a suggestion Washington quickly and emphatically dismissed. Washington believed in the cause of American liberty and resisted the temptation of power. Only a few times in world history had a person in this position voluntarily surrendered all their power. Julius Caesar, William Cromwell, and Napoleon Bonaparte are prime examples of those who seized power at a similar moment. One of the only precedents of rejecting the allure of that amount of power was in ancient Rome when Lucius Quintius Cincinnatus gave up his power on two separate occasions to become a simple farmer. In 1783, Washington had become the American Cincinnatus.

Many of Washington’s fellow Continental Army officers were aware of the historic nature of this decision. As the army was being disbanded, they created a fraternal organization of all the officers in the Continental Army and named it the Society of the Cincinnati. Washington agreed in 1783 to be the first president of this organization. He served in the role until his death in 1799, and the society continues to exist to this day, made up of descendants of the Continental Army officers.

As Washington exited the stage, he said to the Congress: “Having now finished the work assigned me, I retire from the great theater of action; and bidding an affectionate farewell to this august body under whose orders I have so long acted, I here offer my commission and take my leave of all the employments of public life.” Those present were overtaken with emotion and wept. Washington handed over to the Congress his commission dated June 15, 1775, and like that, Washington was once again a simple private citizen.

Washington immediately rode to his home Mount Vernon where he arrived on Christmas Eve. He had finally come home after eight years of war. Washington hoped for a quiet private life and yearned to enjoy the fruits of the American victory under his “own vine and fig tree.”

Having been away from his beloved plantation for more than eight years, he found the place in much need of attention. Washington immediately began to work to improve the farms at Mount Vernon. Agriculture was Washington’s true love. In addition to improving Mount Vernon, he worked to expand his land holdings in the west. He believed the future of the United States was in the west and sought to expand commerce and agriculture that way. In 1785, Washington helped found the Patowmack Company in order to build a canal in Virginia around the Great Falls of the Potomac River and increase trade with the west.

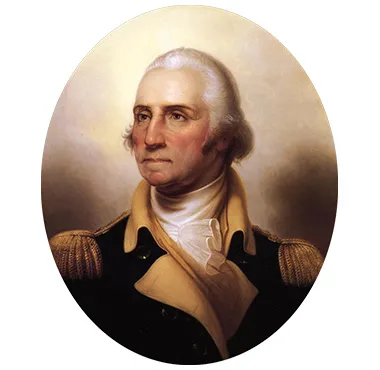

Despite his private endeavors, Washington could not escape the fact that he was one of the most famous people in the world at that time and was almost universally admired and revered. He engaged in constant correspondence with people all around the world and received hundreds of visitors at Mount Vernon in a constant succession. Included in the numerous visitors were former soldiers who served with him, foreign dignitaries, and artists from around the world who sought to capture his likeness.

Though retired from public life, Washington continued to read newspapers from around the country and watched alarming events unfolding in the nation he helped to liberate. He soon began to feel the pressure from many people to return to public life as it became clear that the central government of the United States had become ineffective in the face of mounting problems. The central government was operating under the Articles of Confederation that had been created during the Revolutionary War. These articles gave the central government very little power. Interstate commerce had become very difficult and the government was unable to properly support the state governments. An example of this was in 1787, when the central government was unable to help Massachusetts put down an uprising in the western part of the state known as Shay’s Rebellion. Washington believed the Articles of Confederation should be revised to give the central government more power, but he was hesitant to get involved.

Washington believed that his every move would be scrutinized, both by his contemporaries and by the annals of history. When he was asked by the Commonwealth of Virginia to attend a meeting in Philadelphia to revise the Articles of Confederation, he was wary about agreeing. He did not want to appear to be interested in gaining power and taking control and he did not relish another extended absence from his beloved estate. That being said, he wanted to see the young United States succeed, and this desire ultimately took precedence. After much deliberation and thought, Washington finally agreed to attend the meeting in March of 1787. Summoned by his countrymen and bowing to his duty, Washington would attend a meeting that summer that became known to history as the Constitutional Convention.

In the initial meeting in Philadelphia in May of 1787, Washington was unanimously elected the president of the convention. What began as a meeting to revise the Articles of Confederation soon became a meeting to create a brand-new federal government. While heading this convention, Washington spoke very little to avoid influencing the debates. It was clear, though, as the delegates crafted what would become the new United States Constitution, that the chief executive position was being built with Washington in mind. Washington had always served as a truly unifying figure in the often bitter and divisive politics during this period. In September 1787, with Washington at the helm, the convention finished crafting the new United States Constitution. Now it would require ratification by each of the states in order to go into effect. Washington was a strong proponent and believer of the new constitution, despite its numerous flaws.

Following the convention, Washington once again retired to Mount Vernon. Washington discussed with many people his support for the new Constitution and hoped the state of Virginia would ratify it. By the summer of 1788, enough states had ratified the new Constitution and the creation of the new federal government began.

In the spring of 1789, Washington received the news that he likely knew was coming. He had been unanimously elected as the first President of the United States. Washington again was cautious to accept. He did not want to appear to be power-hungry, but also did not want to evade his duty to his country. He ultimately decided to accept the position and said to the secretary of the Congress who brought the news to Mount Vernon that, “While I realize the arduous nature of the task which is conferred on me and feel my inability to perform it, I wish there may not be reason for regretting the choice.” He believed that he could set the nation on a steady course and then give up the power of the presidency, which he would ultimately do after two four-year terms.

As Washington left Mount Vernon for the new capital city of New York, he described his feelings as “not unlike those of a culprit who is going to the place of his execution.” Washington was unsure of the success of this new endeavor, but he was willing to risk his hard-won reputation and fame on it. Ultimately, his belief in the cause of the new United States outweighed his possible personal losses in the effort. He was willing to sacrifice everything on the new United States.

Washington’s retirement from 1783 to 1789 was short-lived and filled with constant attention to the establishment of the new United States. He would serve from 1789 to 1797 at President and would spend his final retirement at Mount Vernon from 1797 until his death in December of 1799. Washington was always willing to place the interests of the United States of America before his own and was well deserved in earning the name for posterity as “The Father of Our Country.”

Further Reading

- Washington: A Life By: Ron Chernow

- You Never Forget Your First: A Biography of George Washington By: Alexis Coe

- Washington’s Crossing By: David Hackett Fischer

- Washington's End: The Final Years and Forgotten Struggle By: Jonathan Horn

- Valiant Ambition: George Washington, Benedict Arnold, and the Fate of the American Revolution By: Nathaniel Philbrick