George Washington did not start out as the towering figure of American history that he eventually became. Born on February 22, 1732, George was the fifth of his father’s 10 children. The Washingtons had not risen to the heights of Virginia’s elite, but his father, Augustine, was acquiring properties with sufficient slaves to work them and provide a comfortable life for his family. Augustine’s untimely death in 1743 destroyed any hope of an English education for George, but he always remained dedicated to self-improvement.

With Augustine’s passing, George inherited ten slaves and Ferry Farm on the Rappahannock River, where he had spent much of his childhood. His mother, Mary, largely took control of his assets. A taciturn woman quick to criticize, she may have instilled him a lifelong sensitivity to slights. George’s older half-brother, Lawrence, became a surrogate father and early role model. He owned a small farm on the Potomac (Mount Vernon), received an English education, earned a commission in the British army, and was adjutant general of Virginia. George naturally gravitated toward Lawrence and spent many days at Mount Vernon, no doubt escaping his mother’s nagging.

In 1743, Lawrence Washington married Ann Fairfax, catapulting the Washingtons into the top reaches of Virginia’s elite. Fortunately, the Fairfax family took an active interest in George’s future. In 1746, after his mother quashed a plan to seek a naval commission, George took up surveying. It promised a decent income and helped stimulate Washington’s desire to acquire land, which was a path to wealth in Virginia. Working for towns, counties, and the Fairfaxes, Washington earned enough to buy 1500 acres. For the rest of his life, George Washington would actively engage in land speculation.

When Lawrence fell ill, George accompanied him to the Caribbean in November 1751 searching for a cure. It was his only overseas trip and he contracted smallpox, but acquired a lifelong immunity. He returned to Virginia in January 1752, armed with a letter of introduction to Virginia’s new lieutenant governor, Robert Dinwiddie. Lawrence returned separately and then died in July.

Lawrence’s death vacated the post of adjutant general in Virginia and George sought the job, despite being unqualified. Connections helped and he was appointed to Virginia’s southern district, eventually moving to the more prestigious Northern Neck district just before his 21st birthday. He also joined a new Masonic lodge in Fredericksburg, pursuing those positions that would elevate his social standing.

His new military post and ambitions put Washington at the forefront of the French and Indian War. In October 1753, Dinwiddie chose Washington to deliver a message to the French insisting they withdraw their forces from the upper Ohio River valley. It was a perilous trip, involving Washington in diplomacy and espionage. The French rejected Dinwiddie’s message and Washington rushed back to Williamsburg with an Indian trader. The two trekked on foot, dodged Indians, survived a suspected murder attempt, were trapped overnight on a frozen river. Washington reached Virginia’s capital on January 16, 1754, with the French reply. He kept a record of his adventure, which circulated widely as The Journal of Major George Washington, immediately giving him a degree of celebrity on both sides of the Atlantic.

The French and British both asserted their respective claims at roughly the same time. George Washington, now a Lieutenant Colonel in the Virginia militia, led a small force toward the Forks of the Ohio River in modern Pittsburgh, but the French beat him to the prize. He withdrew to a frontier glade called the Great Meadows, ambushed a French force at a place since known as Jumonville Glen, and then built a poorly designed fort that he dubbed Fort Necessity. The French and their Indian allies attacked and compelled Washington to surrender. The terms, written in French, stated that Washington’s attack at Jumonville Glen had resulted in the assassination of the French commander, causing an international scandal. Washington later blamed his translator for not properly explaining these elements of his surrender.

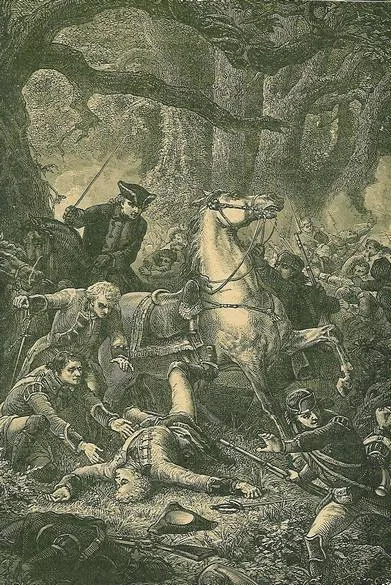

His earliest military experiences added to Washington’s celebrity, particularly in the colonies, but led Europeans to question his judgment. In either case, he learned from his mistakes. When British Major General Edward Braddock arrived off the Virginia coast in February 1755, Washington petitioned to join his staff “to attain knowledge of the military profession.” He joined Braddock on an ill-fated campaign against the new French fort at the Forks of the Ohio. While Washington still sought a formal commission in the British Army, Braddock would only give him the temporary rank of brevet captain, inferior to a regular British officer. Braddock plodded toward Fort Duquesne with two regiments of British regulars and assorted colonial militia, slowed by the need to build a road across the wilderness. Washington fell ill and made portions of the journey in a wagon at the rear. On July 9, 1755 Native Americans and Frenchmen ambushed Braddock’s advance guard. The army quickly collapsed, sustaining large losses, including many of its officers and General Braddock, who was mortally wounded. Washington stepped up to fill the void, riding forward despite his illness. He relayed orders, rallied troops, and had two horses shot from underneath him. Four bullets pierced his coat and hat, but the young officer emerged unscathed, hero of the day.

After Braddock’s defeat, Virginia moved quickly to raise funds and defend its frontier. Lieutenant Governor Dinwiddie made Washington a colonel in the colony’s service and put him in command of its defensive force. He was only twenty-three. Washington spent the next three years contending with undisciplined troops, uncooperative and condescending British authorities, an assembly that inadequately provided supplies, and contradictory policies from other colonies, all before he had to deal with raids on the Virginia frontier. But, Washington persevered and again learned, this time how to raise, train, discipline, and maintain military forces in the field.

Washington’s military career started to wind down in 1758. He lost an argument over military strategy and how best to capture Fort Duquesne. When the fort finally fell, Washington resigned his colonial commission. But, his career outside the military continued on an upward path. He won election to the House of Burgesses from Frederick County, Virginia, where he had made his wartime headquarters and moved into Mount Vernon, which he had rented from his sister-in-law. He also looked to his personal life and courted the newly widowed Martha Dandridge Custis. She was wealthy and had two children, John, who went by “Jacky,” and Martha, who went by “Patcy.” So, when George and Martha married in January 1759, George Washington became an instant family man with a four-year-old Jacky and a two-year-old Patsy underfoot.

Newly married, Washington turned toward the life of a genteel planter, expanding Mount Vernon and acquiring land and the slaves to work it, while living beyond his means. Most of Washington’s working farms were not suited to tobacco, so he experimented with a variety of crops. He continued to speculate in land, particularly on the frontier. Washington also started a range of businesses, such as milling and fishing, finding success in economic diversification. It was the same practicality and willingness to experiment that he had demonstrated as a frontier commander.

George and Martha pursued an active social life of balls, fox hunts, theater, cards, and parlor games with their friends and neighbors across Virginia. By all accounts, Washington was as graceful on the dance floor as he was on horseback. Martha attended church dutifully and George became a vestryman in the Truro parish of the Church of England, but he often preferred fox hunting to services.

Washington remained a voracious reader and closely followed the political and business news of the day. They contributed to a political awakening that often found him at odds with British colonial policy, particularly as it related to colonial rights and the prerogatives and authority of Parliament. Washington was no firebrand, but his frustration with Britain grew and by 1769, he wrote his neighbor George Mason:

“At a time when our lordly Masters in Great Britain will be satisfied with nothing less than the deprivation of American freedom, it seems highly necessary that something shou’d be done to avert the stroke and maintain the liberty which we have derived from our Ancestors…That no man shou’d scruple, or hesitate a moment to use a—ms [arms] in defence of so valuable a blessing, on which all the good and evil of life depends; is clearly my opinion; Yet A—ms I wou’d beg leave to add, should be the last resource."

Washington was a dutiful legislator but avoided public speaking. Instead, he quietly formed political alliances, particularly over the social events that always occurred around the margins of an assembly meeting. Always practical and to-the-point, he led efforts to shift from formal protest of specific British actions to more direct measures, such as nonimportation agreements, boycotts, and economic independence. By 1774, his record as a military officer, success as a planter, reliability as a legislator, and growing commitment to the Patriot cause were clear. A state convention voted to send him and six others to the first Continental Congress.

When Washington returned home in October 1774, he began drilling a company of Fairfax militia in Alexandria and helped raise and finance a second company, helping put Virginia on a war footing. After reading of Lexington and Concord, he set out for the Second Continental Congress in May 1775 and included a uniform in his luggage, as if he knew he was going to war. When the Second Continental Congress concluded it needed a commander to bring order to the Army of the United Colonies besieging British troops in Boston, Washington was the natural choice.