Nancy Hart's confrontation with Tory intruders in her Georgia cabin, which earned her a reputation as one of Georgia's Revolutionary heroine.

You've already been introduced to some of the fascinating Georgians, loyalist and Patriot, who shaped the course of the American War for Independence, but there are many more. Founders and everyday folk alike contributed to the youngest colony’s unique role in the Revolution.

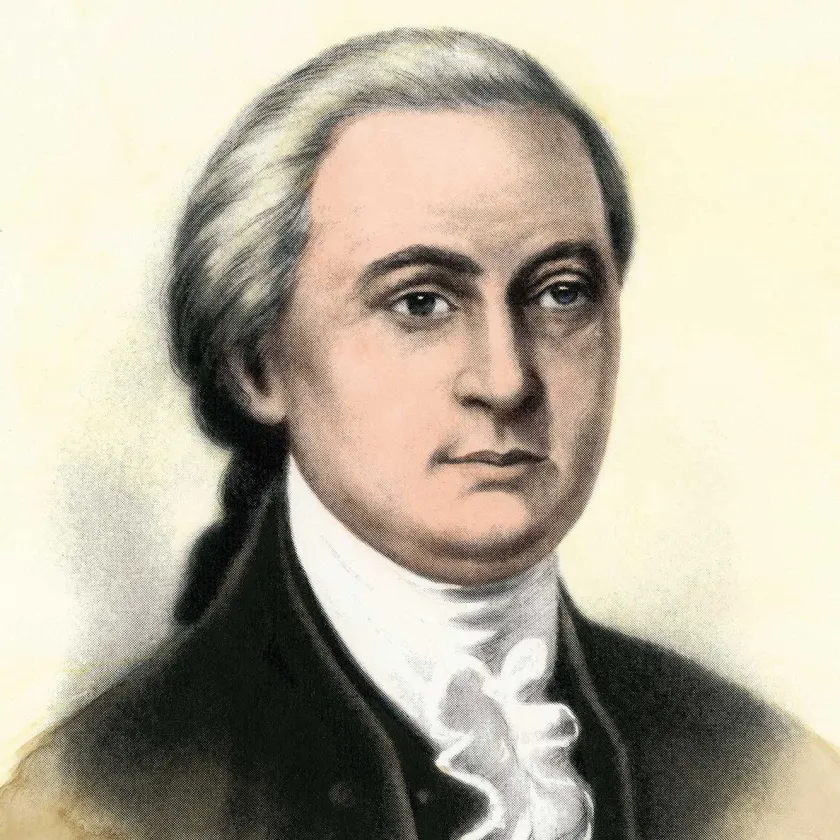

Lyman Hall and George Walton

Lyman Hall and George Walton served alongside Button Gwinnett at the Second Continental Congress, also signing the Declaration of Independence. Interestingly, none of the three were born in the new state they represented: Gwinnett was born in Britain, Hall in Connecticut and Walton in Virginia. Three contiguous counties in northeast Georgia are named after this trio.

Walton, who had been an ally of Lachlan MacIntosh, initially apprenticed as a carpenter, but went on to become one of the most successful lawyers in Georgia. He led a battalion at the Battle of Savannah, where he was wounded and captured. After spending nearly a year in Sunbury Prison, he was released in a prisoner exchange in October 1779 and almost immediately elected governor of Georgia. Later in life, he again served as governor and in the U.S. Senate, and helped found what is now the University of Georgia.

Hall was a Yale University–educated minister and doctor who first moved to Dorchester, South Carolina, near Charleston, and subsequently, with a large Congregationalist community, to what is now Liberty County, Georgia. Hall was a prominent citizen in the new town of Sunbury, which was solidly Patriot in sentiment, despite being surrounded by loyalist communities. Although Georgia had not been represented in the First Continental Congress, Hall’s was one of the voices that encouraged parishes to send representatives to the Second. He himself was selected for this role and arrived in 1775, ultimately one of four physicians to sign the Declaration. Later he served as governor of Georgia for a short time, advocating for the creation of a state university, and when his term expired, he resumed his medical practice.

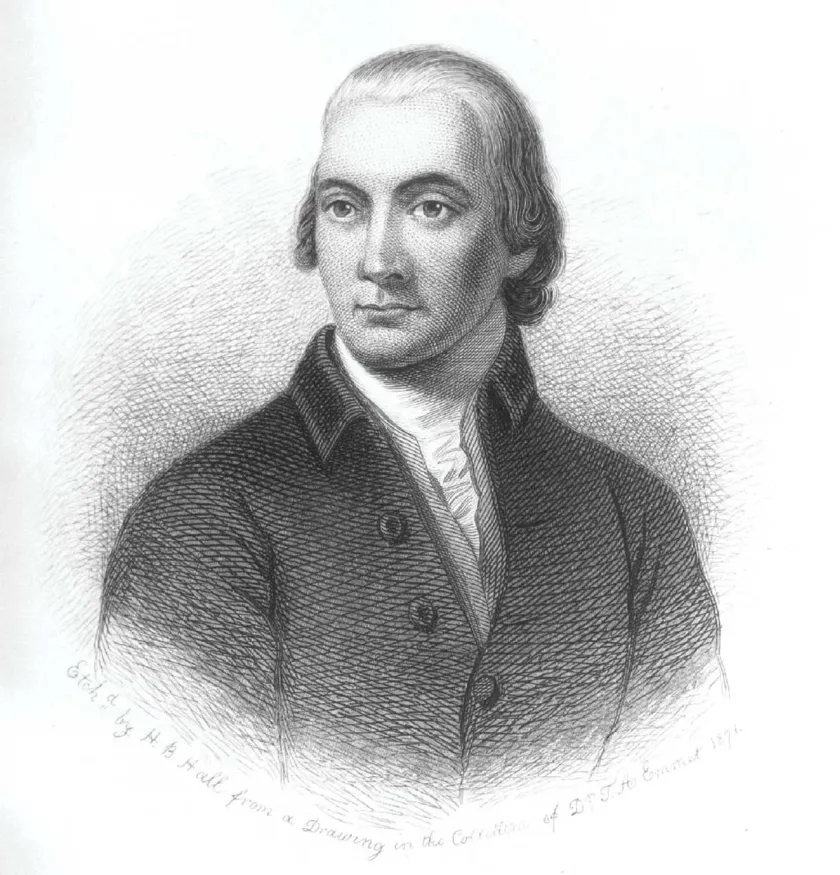

Archibald Bulloch

Archibald Bulloch was an early delegate to the Continental Congress and close ally of John Adams, known to express strong sentiments like “This is no time to talk of moderation; in the present instance it ceases to be a virtue.” But he had voluntarily left Philadelphia to return to Georgia and fight in the ranks. He took part in the Battle of the Rice Boats and the Battle of Tybee Island, and in June 1776 was named “President and Commander-in-Chief of Georgia” under the temporary republican government.

On February 20, 1777, he signed the state constitution, and two days later, according to the New Georgia Encyclopedia, in the face of an invasion by the British from Florida, Georgia’s Council of Safety requested that Bulloch “take upon himself the whole Executive Powers of Government.” The powers offered were nearly dictatorial, but two days later, Bulloch was dead in circumstances never fully known — some speculate poison. But Bulloch had married in 1764, and among his notable descendants was great-great-grandson President Theodore Roosevelt.

The Glascock Family

Several generations of the Glascock family of Augusta played prominent roles in the Revolution and early republic. Colonel William Glascock, a veteran of the French and Indian War, served as chairman of the executive counsel of Georgia and was labeled as a “Rebel Counselor” in the Disqualifying Act of 1780 while the state was under British occupation. His son, Brigadier General Thomas Glascock, was twice captured by the British, but is credited with rescuing the wounded General Casimir Pulaski from the British. His courage was such that George Washington declared Glascock “Marshal of Georgia,” a title that is still treasured by his descendants, including two sons who also rose to the rank of general, serving in the War of 1812 and Seminole Wars.

Ann Morgan “Nancy” Hart

Ann Morgan “Nancy” Hart was a cousin of General Daniel Morgan and a patriot spy in the backcountry Broad River Valley. According to legend, British soldiers came to Nancy’s home to question her about assisting an escaped Patriot. When they demanded food and drink, Nancy obliged with unusual hospitality, all the while discreetly removing the soldiers’ muskets from the stack they had formed in a corner.

Nancy had passed two of the guns to her 12-year-old daughter Sukey through a gap in the wall before the soldiers noticed. Nancy then instructed the soldiers to remain where they were — when one rose to approach her, she shot him dead, wounded another and took the remaining four hostage. Sukey ran to tell her father, who returned to the cabin. The Harts and their neighbors decided to hang the soldiers from a nearby tree. In 1912, an archaeological excavation of the land near the Harts’ cabin unearthed six skeletons, suggesting that some version of the myth was true.

John Dooly

Merchant, surveyor and land developer John Dooly was among many Georgians who initially opposed the revolution, but was later swayed by its opportunity for social, economic and political progress on the southern frontier, which the British had largely ignored, and he took up arms. On February 14, 1779, Colonel Andrew Pickens of the South Carolina militia and Dooly attacked at Kettle Creek and routed roughly 600 Carolina Tories, who were attempting to connect with British forces in Augusta. Ongoing Patriot opposition in America’s backcountry pushed the British back to the coast, and Dooly — acting as the highest-ranking military officer, as a member of the dominant legislative body in Georgia and as state’s attorney — began to arrest, chain, try and even execute loyalists as traitors.

In June 1779, he assembled some 400 militiamen for an uncoordinated attempt to take back Savannah as the British garrison dwindled. He participated in the Franco-American siege that September and another failed October 9 attack. In May 1780, with the Georgia interior overrun, Dooly was one of many militiamen who surrendered but were allowed home on parole. Soon thereafter, the Patriot hero was murdered, supposedly in front of his family. However, whether it was an example of the cynical “Georgia parole” that claimed the lives of prisoners in the Southern Campaigns when the fortunes of war shifted, revenge exacted by pre-war creditors or another grievance from his enemies is uncertain.