Armed with orders from General Sir Henry Clinton, commander in chief of the British Army in America, and backed by just over 3,000 tough British and German regulars and American loyalists, Lieutenant Colonel Archibald Campbell, commander of the Second Battalion, 71st Regiment of Foot (Fraser’s Highlanders), set forth on an “Enterprize against the Rebels in Georgia.” Along the way, he penned a remarkable journal of his quest to seize and subdue the southernmost rebel colony.

Campbell’s larger mission was to inaugurate Britain’s more ambitious Southern strategy to return the “deluded Colonies” of Georgia and the Carolinas to the imperial fold. The 1778 Franco-American alliance had turned the American War for Independence from a colonial rebellion into a European war. Despite this, Secretary of State for the Colonies George Germain, as well as Clinton and George III, believed there was an opportunity to rescue British fortunes - reports swirled of loyalists awaiting the King’s army.

Armed with a local commission as brigadier general, Campbell departed the New York area with his invasion flotilla on November 26. The transports, estimated to have been anywhere between 20 and 56 boats, sailed with an escort under the command of Commodore Hyde Parker: the Phoenix (44 guns), Vigilant (24 guns), Foy (20 guns), Keppel (16 guns), Greenwich (12 guns) and Alert (8 guns), and the row galley Comet. The transports carried eight battalions of infantry but just “36 Men [and eight guns] of the [4th Battalion] Royal Artillery (a miserable Proportion for so many Regiments of Foot).” In total, it made 3,041 rank and file.

Unknown to Campbell or Clinton, Brigadier General Augustine Prévost at St. Augustine, East Florida, had ordered forces toward Sunbury, Georgia, to forage and, if possible, capture Fort Morris, some 26 miles south-southwest of Savannah; the fort guarded the seaward approach on the Medway River. On October 20, Clinton had ordered Prévost to invade from the south, in conjunction with Campbell’s descent from New York. The orders, however, did not arrive until November 27, a week after Prévost’s foragers had departed and the day after Campbell had sailed. While at sea, Campbell wrote to Governor Patrick Tonyn of East Florida and to General Prévost, informing them of his mission. Campbell requested Tonyn work with Superintendent of Indian Affairs Colonel John Stuart to “make a Diversion in … the Back Woods of Georgia … as far as the Frontiers of South Carolina.” Campbell requested that Prévost advance to the Altamaha River, about 52 miles south-southwest of Savannah, to divert attention from Campbell’s attack.

The voyage south was difficult; the transports and escorts were “repeatedly dispersed by hard Weather,” but by December 22, they were “off Charles Town … and the Weather easy and favourable.” Most of the fleet anchored off Ossabaw Island on December 23, about 20 miles south-southeast of the mouth of the Savannah River. “One Transport and two Horse Sloops,” however, were missing. With most of his forces concentrated, Campbell was poised to advance.

Campbell and Parker conferred, and on Christmas Eve the flotilla “stood in for the Mouth of the Savanah River.” An unexpected gift greeted them: the missing transport Dorothy, carrying 200 Highlanders of the First Battalion. Most of the fleet entered the river on Christmas Eve, and Campbell issued landing orders. Warships would “cover the Disembarkation,” as the 71st’s two light infantry companies secured the beachhead. Soldiers were ordered to carry 60 rounds, two spare flints, a blanket, three days’ rations and one day’s rum. Rather than firing from their “Flat Bottomed Boats,” Campbell ordered his troops to exercise patience and then close with the enemy using their bayonets.

Before proceeding upriver, Campbell sought out intelligence on his enemy. The two light infantry companies from the 71st, under the command of Captain Sir James Baird and Captain Charles Cameron, landed on Tybee Island to “stretch their Limbs, and … search for Intelligence, Horses and fresh Stock.” They found nothing but some wild horses. That evening, Baird’s company boarded flat boats, made its way westward through Tybee Creek to Wilmington River and landed within a few miles of Savannah.

The next morning, Baird returned with two local prisoners, from whom Campbell learned of the American troop dispositions: Major General Robert Howe of North Carolina commanded two brigades of South Carolina and Georgia Continentals and militia. But the estimate of American troops was double the actual strength of 854 soldiers and around nine artillery pieces. Campbell also learned of a potential landing site at Sheridoe’s [Girardeau’s] Plantation, some 12 Miles above Tybee Island, and just one mile, along an excellent road, from Savannah.

After considering this information, Campbell proposed that the force “should push on Shore in the middle of the Night” at the plantation with “1000 Men, and establish a Footing” before dawn, with the rest of the invasion force following. He planned on taking the “Town by Surpsize.” Parker agreed, but storms and high winds delayed the attack until Monday morning, December 28. Transports carrying the soldiers followed and a two-hour cannonade commenced, although the shots initially fell short. Ultimately, the British drove off their opponents.

By 4:00 p.m., the tide was out, and the transports were grounded six miles short of their target, so Campbell put off landing until the next morning. Flow tide began at 10:09 p.m., with full flood at 3:35 a.m. Campbell would have a limited window to act. The cannon fire and easily visible masts of the British vessels erased any chances of surprise, but Campbell was not dissuaded. Orders went out for a first landing wave to board boats and concentrate that night under the stern of Vigilant for an immediate landing the next morning. Baird’s light infantry company was delayed, its transports having run aground two miles downriver.

When the sun rose at 7:25 a.m., the tide was fast ebbing, but the First Division was ready and “Baird’s Company, which was then … 500 Yards in the Rear, [was] pulling at oars briskly to the Rendezvous.” While Campbell and Parker were doing what little they could to speed along Baird’s approach, Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Innes fretted over the tide and ordered the boats to make for the shore immediately. Campbell returned in time to halt the redirection, then made for Cameron’s light infantry, stopping its advance.

Captain John Carraway Smith and 40 outnumbered soldiers of the Third South Carolina faced the British from atop Brewton’s Hill, the heights that rose above Girardeau’s Plantation. Smith’s Continentals commanded a “new and extremely irregular” road with a “deep Ditch on each side” running from the river. Rice swamps extended to the east and west, with the hill ahead of the landing rising about 40 feet. Smith’s South Carolinians had taken position in the houses and outbuildings of the plantation, and the surrounding terrain gave them advantage: The narrow road and surrounding rice fields prevented dispersal and rapid movement, and the heights gave Smith good observation opportunities. With limited options available, Campbell relied on a “forlorn Hope … [of] A Corporal and four Highlanders” to lead the assault. About 50 yards to their rear, a “Sergeant and 12 Highlanders” trailed. Campbell “led the Remainder … in person at a slow pace towards the Bluff.” This enabled Cameron to observe and command and gave time for the follow-on forces to flow onto the beachhead as the assault force advanced.

Five hundred British soldiers now occupied the beachhead. It was time to advance and “dislodge the Enemy.” Campbell ordered the “forlorn Hope to move Briskly” forward; they alone would return American fire, while the main body was to assault and seize the position.

Fortunately for Campbell, the Americans fired early, and few rounds struck the British from the 100-yard range. The light infantry charged as Smith’s company “retreated with precipitation by the Back Doors and Windows.” In less than three minutes, Campbell had seized the high ground, losing Captain Cameron and three Highlanders killed, with five more wounded. But Campbell was fortunate, and he knew it, recording in his journal: “Had the Rebels stationed Four Pieces of Cannon on this Bluff with 500 Men for its Defence, it is more than probable, they would have destroyed the greatest part of this Division.”

Colonel Samuel Elbert of the Second Georgia Continentals had suggested posting 200 soldiers on the bluff, but General Howe had thought that a landing at Girardeau’s Plantation would be a deception. When the landing commenced, Captain Smith sent a messenger to Howe, who never received it and had no idea of the landing until the firing began.

After seizing Brewton’s Bluff, the light infantry advanced, and the rest of the invasion force landed. They sent out patrols to reconnoiter the woods bordering the plantation, and the roads beyond to scout for the enemy. Once Campbell was satisfied, he advanced south. The light companies led the advance, followed by the First Battalion of Highlanders, all the while taking ineffective fire from American naval forces on the river.

Campbell learned that the Americans were “forming in Line about half a Mile South” of Savannah. But because of the lack of transport, it took until about noon for the rest of his army to land. As they advanced southward, each battalion sent out flankers left and right for security. Roughly one mile onward, “they fell in with the Great Road leading from Thunder Bolt Bluff to the Town of Savannah” and left one Hessian regiment as rear security.

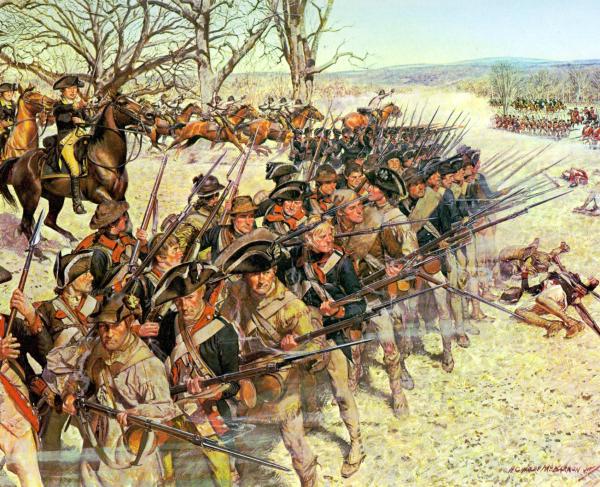

By about 2:00 p.m., the British reached a point about 800 yards from the American defenses, where they formed a line along a fence on Governor Sir James Wright’s plantation. To the west, the Americans had four field pieces, which opened fire on the light infantry. Campbell ordered Captain Baird to avoid exposing his soldiers to enemy fire. The main body was to the east, covered and concealed by the descending ground. While this took place, Campbell climbed a tree on the left of the light infantry, observed the American lines and considered his next move.

The Americans had formed in a level area facing east; their left extended north toward the rice fields, while their right tied in on a thick wood that extended well to the south. Howe had formed the South Carolinians under Lieutenant Colonel Isaac Huger to the south of the road, and Elbert and the Georgians to the north in a shallow V, with the arms presented eastward. To the west, Georgia militia faced southeast, perpendicular to the Ogeechee Road “near to the New Barracks,” with the left resting on the road. They had some artillery and stood behind breastworks.

Quamino, an enslaved man from Wright’s plantation, gave Campbell intelligence about the American movements and offered to “lead the Troops … through the Swamp upon the Enemy’s Right.” Based upon this information and his observations, Campbell formulated his final plan: He would send the light infantry against the American right, the southern position, to “make an Impression,” and himself would lead the attack against the South Carolinians and Georgians to his front.

Campbell began by deceiving the Americans. He marched the light infantry and First Battalion of Highlanders north toward the river, but then doubled back and used “A happy Fall of Ground” to the east of the line to march south, out of view. Led by the Quamino through the swamps, Baird and the light infantry followed.

Campbell posted an officer in a “high Tree to watch the Motions of the Light Infantry” and signal when firing commenced from the southern American positions. Campbell next deployed his artillery, “concealed by a Swell of Ground in the Front.” Once the engagement began, the artillery would push forward and fire on the American line. South of the artillery, a Hessian regiment formed. Throughout the deployment, the Americans fired a “loose Cannonade, without any Return on our part.” Not long after, Campbell received the signal: The light infantry had made contact.

With the light infantry demonstrating against the southern defenses, the main effort commenced. Artillery “broke the Enemy’s Line” even before the infantry advanced, and the American “Retreat was rapid beyond Conception.” Campbell’s infantry gained the high ground from the southeast.

Soon, “a Body of the Rebel Militia appeared” in front of the Highlanders. Campbell was prepared for a fight, but instead received the surrender of Savannah’s militia, which “grounded their Arms.” A company of Highlanders entered Savannah’s fortifications and “gave three Cheers.” The city had fallen, and Campbell’s troops pursued the remaining militia through Savannah.

Events on the south side were much the same. Baird’s light infantry routed the Georgia militia in time to strike the Georgians and South Carolinians who fled from Campbell in the flank. This attack drove the shattered brigades past the Yamacraw Bluffs on the town’s west side and into the marshes below.

Savannah fell to the British on December 29, 1778. In early January, Sunbury, the last American-held post on the Georgia coast, was captured by Prévost coming north from East Florida. On March 8, Governor Sir James Wright received orders from Lord George Germain, the colonial secretary, to prepare for his return to office as royal governor of Georgia. The first phase in Britain’s reconquest of the southern colonies had been a success.

Related Battles

948

155