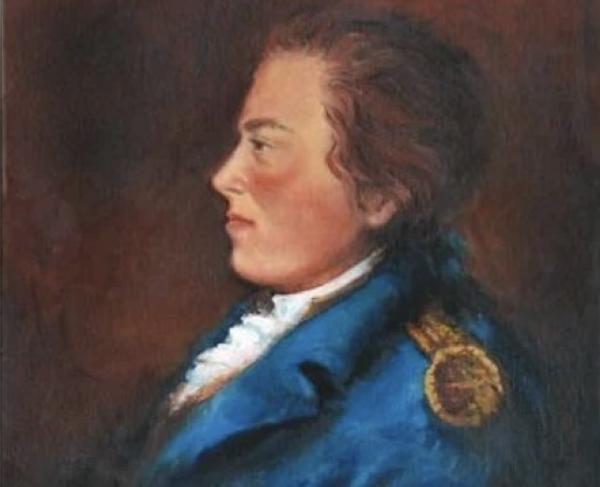

John Dooly

A name that abounds in Georgia legend, John Dooley was not a native to the area. Dooley’s colonial origins lay in South Carolina where he worked as a merchant, surveyor, and land developer in the 1760s. It was in 1772 that Dooley had Georgia on his mind when he mortgaged 2,050 acres of his South Carolina land to finance investment in the neighboring colony of Georgia. His investment led him to become a surveyor in Georgia, where he eventually took control of a 500 acre plantation situated upon the Savannah River.

The Southern colony had initially opposed the revolution because of their peaceful lives under Georgia’s progressive royal governor, Sir James Wright. Many Georgia men, including Dooly, signed protests in opposition to the oncoming conflict between Patriot and British forces. While the Southern colony had little connection to the colonial unrest in Boston, it depended upon the British for protection against Native Americans. Dooly actively participated in the efforts for home defense by serving as a colonel in a vigilante militia.

While initially opposed to revolution, Dooly had been slowly swayed to the side of revolution. Georgia rebels saw the revolution as an opportunity for social, economic, and political progress in the southern frontier, an issue that had laid idle in the hands of British rule. In his revolutionary pursuits, Dooly stepped up as captain of his local militia company. He also became justice of the peace and deputy surveyor.

Defending his adopted home of Georgia, Dooly and his company marched to Savannah in late 1775 to provide defense against arriving British ships. In the summer of 1776, Dooly and his men proceeded to join an expedition that resulted in the destruction of two Cherokee villages. By 1777, Dooly became captain of a new Georgia Continental cavalry regiment. As captain of a new regiment, Dooly set forth on a journey to recruit. He enlisted 97 men in North Carolina and Virginia by illegally signing on deserters. It was during his recruiting mission in July of 1777 that Dooly learned that his brother had been killed in an ambush led by Creek Indians. Learning such news, he seized an oncoming Creek peace delegation so to seek revenge for the death of his brother. Upon Dooly’s unruly action, his superiors were infuriated and compelled him to release the delegation, stand trial, and resign from his position. However, it wasn’t long until Dooly returned to a position of power.

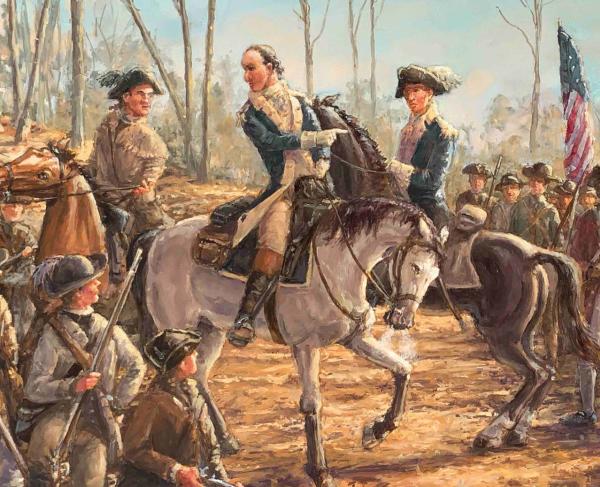

Within a year Dooly became a representative for Wilkes County in Georgia’s new legislative body. In addition, he became colonel of the Wilkes County militia. He was celebrated for his victory against Creek raiders in the summer of 1778. However, Dooly was not known for his compliancy and became a foe of Brigadier General Andrew Williamson when he failed to cooperate with South Carolina militia when they came to the aid of Wilkes County. Wilkes County was indeed in need of assistance as Georgia’s capital, Savannah, was captured by British forces in December of 1778. Thus began a British surge throughout Georgia, driving Dooly to call on help from Colonel Andrew Pickens, Williamson’s subordinate. On February 14th, 1779, Pickens and Dooly attacked at Kettle Creek and routed roughly 600 Carolina Tories, who were attempting to connect with British forces in Augusta. In March, Pickens and Dooly continued to defend the frontier and steered a campaign that fended off a massive force of British-allied Native Americans.

With outstanding Patriot opposition in America’s backcountry, the British withdrew to the coast. Dooly then, acting as the highest-ranking military officer, as a member of the dominant legislative body in Georgia, and as state’s attorney, began his quest to hold Loyalists accountable for their actions. He had them arrested, chained, and tried as traitors – two such Loyalists were even executed!

Dooly’s military service did not cease as he continued to defend Georgia from the British threat. In June of 1779 Dooly assembled approximately 400 militiamen in an attempt to take back Savannah as British troops gradually left to focus on the invasion of South Carolina. Due to lack of coordination, the effort amounted to little more than a raid. The fight for Savannah was not over in the least bit. By September of 1779, American and French forces laid siege to the city with Dooly and his men joining in on the failed attack on October 9th.

The bad luck worsened as British forces overran Georgia and South Carolina in May of 1780. Dooly and many of his militiamen surrendered themselves and thus, became prisoners of war. The British took control of colonial governments and banned Patriot leaders from holding office. Not only that, Dooly and his men were also forced to serve in the King’s militia. Even worse, Dooly was pressed for debts by prewar creditors.

Dooly had made enemies and continued to frustrate Loyalists. He had been pinned as a participant in a September 1780 attack on the King’s garrison in Augusta. Such a pinning led to his murder, supposedly orchestrated right in front of Dooly’s family. A man of the frontier and ardent advocate for societal change, Dooly was honored for his devotion to the revolutionary cause in 1821 when Dooly County was named for the famed colonel.

Related Battles

21

115

948

155