If the American Revolution created the modern idea of self-governing societies, it surely produced leaders who could enact those principles for others to follow. Once again, we come to George Washington. For all that has been said and written about America’s favorite Founding Father, one distinct aspect is generally overlooked when we discuss him. What drove his philosophy? We know he was educated, but he did not attend university like many of his contemporaries. He was self-conscious of this, and it led him to prefer listening over speaking when in meetings and in public. He was also a great lover of history, and found particular solace in the heroic tales of Cincinnatus, the Roman farmer turned general who saved the republic, relinquished power, and returned to his farm to live in peace. This fabled tale became widely popular in ancient Rome. It signified the value of republican virtue. Two events in 1783 would show how Washington sought to emulate him.

By 1783, the war was finally coming to an end. British and American diplomats were busy in Paris ironing out the details of the treaty to end the war, and officially recognize the United States as a sovereign country. In North America, the British army had abandoned any new offensive military campaigns, and were largely held up in the New York City area. Other outposts in the Canadian regions remained occupied, but posed little threat to the peace negotiations. No, the looming threat in 1783 came from the Continental army itself.

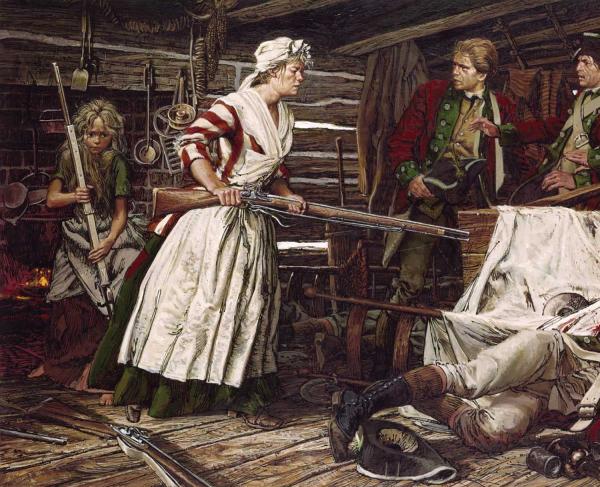

The War of Independence had been fought for the principles of liberty, freedom, and self-government. But these concepts did not pay the bills. Soldiers, including officers, wanted to be paid for their combat service. Most soldiers who had left their homes had also left their professions. One could not earn an income being a soldier. It simply did not pay enough, if anything at all. For some officers, they joined the army with the promise of glory on the battlefield - and being compensated for it. Since many officers came from wealthier backgrounds, many used their private funds to pay for supplies for the army, and expected to be reimbursed. According to the times, many felt disrespected and their honor slighted when Congress came up short or forgot altogether. Tensions within the American ranks had boiled over before. Small mutinies had occurred, and were stamped out before they could spawn larger desertions. However, the threat of mutiny by a large group of senior officers was something entirely new, terrifying, and potentially fatal to the American Revolution.

The Continental army ceded its authority over to the Congress. This was purposeful as it was symbolic. Standing armies were viewed as threatening to peaceful republican civilizations, and the strongest voices opposing British taxation prior to the war were equally opposed to the British army enforcing those taxes. When the war began, there was disagreement over how the new American army should be outfitted and molded. Some Congressional delegates feared a “continental force” and preferred state militias. The problem with militias were that they often came-and-went without any controlling authority to muster them into regular order. Militias could be useful to fend off skirmishes, but they were largely viewed as disorganized and unreliable when asked to head into battling the regular British army forces. Even still, when the Continental army formed in 1775, regional tensions factored into how the army internally identified itself. Washington, to his credit, purposely devised the army to meld the regional differences of the men into one nationally identifying force. This proved troublesome from the outset, coupled with the reliability of the newly cemented states to pay their coffers.

Before and after the Articles of Confederation were ratified, the individual states held most of the leverage when it came to appropriating funds that Congress sought. Though it was the responsibility of Congress to pay the soldiers of the army, all Congress could effectively do was ask the states to give them the money they had promised. It could do no more. Because local economies were devastated by the war, and national inflation had crippled the continental economy, most states refused to pay the appropriated funds. Continental soldiers did not want to hear this. It was them who were on the front lines, fighting, starving, freezing, sweating, and dying. By 1783, with the war winding down, many of the men had had enough.

Instigated by a few Congressional members who were unhappy with the binds on their legislative powers, several senior officers within the Continental army began to hatch a plot that could jeopardize the gains made with the war. If Congress did not pay the soldiers what they had been promised, the Continental army would refuse to disband once the war officially ended. The threat signified two main points: 1. The army would become autonomous and reject the civilian authority Congress had over it. 2. The army would likely march on Philadelphia and hold the Congress hostage until their demands were met and/or perform a coup to take control of the United States. Both ideas would effectively destroy what the Revolution was about, and prove the nay-sayers correct that all revolutions eventually cannibalized themselves. The senior officers exchanged their letters in secret, and developed their intentions behind Washington.

There was one problem: Washington found out about their plot. A letter circulated through the encampment at Newburgh, NY on March 10. Seeking to reassure his officers and call for resolve, Washington issued general orders denouncing the plotter’s intentions, and requested that a meeting be held to settle the issues. A meeting among the officer branch was called for March 15, 1783, at the senior officer’s building. Washington made it known he would not be attending. The plotting officers felt confident they would get their demands onto paper, and send it off to Congress. The fate of the nation rested with their signatures.

At noon on March 15, the Ides of March, the senior officers met in conference. Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates presided over the meeting. Gates, whose career was checkered, now sat at the head of what might become the defining moment of the war. Just as the meeting was set to begin, the front door swung open and Washington walked in. The officers were shocked. The commander walked to the front of the room and took leave of Gates. The mood in the room quickly shifted back to the reasons for their gathering. Sensing this, Washington pulled a letter from his jacket, and spoke on behalf of what they had sought to do in light of their struggle against the British. He cautioned patience, and spelled out the importance of Congress, and of civilian authority. After a few minutes, the American commander was finished. Around the room, his senior officers sat in contempt. The mood had not lightened or changed. Washington had failed. It was in this moment that George Washington dug deep, literally. Channeling his favorite play, “Cato,” he pulled out a second letter from his breast pocket and began reading. Except, this time his voice began to crack. His hands tremored as he held the paper, and eyes around the room took notice. Washington then reached into his pocket and pulled out a pair of spectacles. He had been wearing reading glasses for much of the war, but was hesitant to use them outside of his private quarters. For many of his senior officers, this was the first time they saw him wearing glasses. The mood began to soften. Washington cleared his throat and continued, “Gentleman, you will permit me. I have not only gone grey, but almost blind in the service to my country.” He then spoke about how much he had personally sacrificed during the war. He reminded the men that he had never once left their side, had fought for them on and off the battlefield whenever he could, and that his loyalty to the duty that which he was assigned was paramount to every other action or decision he had made. He then removed his glasses and dismissed himself. The mood was quiet somber now, and many officers later reported that most openly wept. Within minutes of his departure, the senior officers drafted a letter to Congress with their intentions: the army would respect the civilian authority of Congress over the military, and that the senior officers would accept their pay at the earliest convenience of Congress. Washington had disarmed the mob without lifting his sword. In this fight, his weapon of choice were a pair of reading spectacles. Throw in a mixture of theatrical poise and historical sincerity, and the desired effect had swayed the room. Indeed, only he could have performed such a move. Had he failed, the war could have turned into something more akin to the French Revolution.

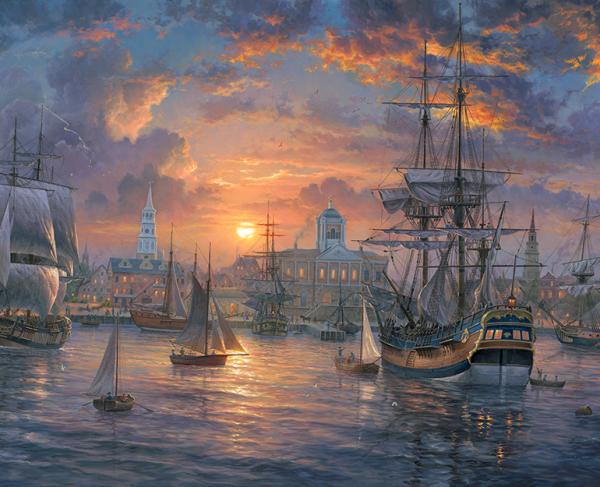

In December, with much of his army finally home for good, Gen. George Washington rode his horse from New York to Annapolis, Maryland to meet the Confederation Congress. Along the way, Washington was hailed in every town as the great conqueror. He was blessed by every man, woman, and child. Taverns cheered him and lavish dinners were thrown on his behalf. He was the first American hero. And then he reached Annapolis. On December 23, 1783, George Washington resigned as commander in chief of the Continental Army. Those who knew him were not shocked by his conduct. He had been reluctant to take on the command to begin with. And now, in victory, he did not seek a station of power. He sought his retirement and his farm. He would be home for Christmas. Years later, when sitting for painter Benjamin West, King George III said that Washington was, “the greatest character of the age” for giving up power. Washington set the precedent for the American ideal that obtaining power was not the main objective in life. In relinquishing his command, the army would not have a dictator at its helm. And in embodying the principles of the American Revolution, George Washington once again proved why he was and remains America’s indispensable man.