Robert Smalls eased the vessel away from the pier and backed into the harbor. The night air was still, and Smalls could smell the sea life as the steamship churned up the brackish water and turned southeast. As Smalls passed the batteries, he took note of the soldiers standing their watches as he had a hundred times before. When the ship entered the main channel, Smalls looked around and was comforted to see his family and many of his friends on board with him. Moving faster toward the open sea in the first light of dawn, Smalls must have felt the freedom and exhilaration that only the master of a ship at sea can truly feel. Except that this was not Smalls’ ship; and he was not quite yet a free man.

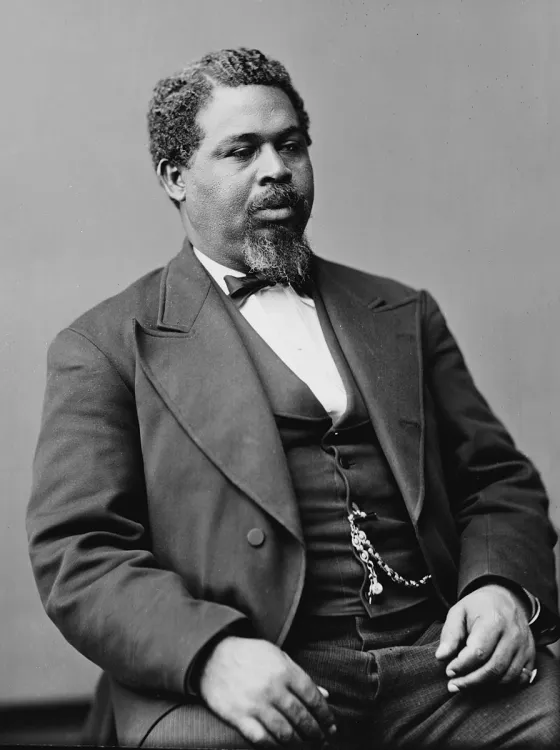

Robert Smalls was born into slavery in Beaufort, South Carolina in 1839. As a boy, he worked with his mother in the relative comfort of their owner’s home on the plantation. His mother had worked hard in the fields, so she made sure Robert witnessed the horrors that the other slaves endured. When Smalls turned 12, at his mother’s request, the owner sent Robert to nearby Charleston to be hired as a worker. Smalls worked at odd jobs around the city as a lamplighter, a stevedore, and in a hotel, where he met Hannah Jones. Robert and Hannah were married in 1856 and they had two children. For a slave making a meager wage, the price to buy your family’s freedom was expensive, and knowing what plantation life for a slave family was like, Smalls began to think of other ways to obtain freedom for his wife and children.

Smalls’ work led him to the wharves and piers of the bustling Charleston waterfront, where he eventually settled in and worked various jobs as a longshoreman, sailmaker, and a rigger. He grew to like the sea, and as he worked on boats he became intimately familiar with the tides, sandbars, and currents of Charleston Harbor. Harbor pilots were needed to safely guide the big, cotton-carrying ships to and from the piers. At the time, blacks could not be hired as pilots, but by all accounts, Smalls was qualified to be one. His experience and navigational skills led him to be trusted by the white ship owners up and down the waterfront along Bay Street.

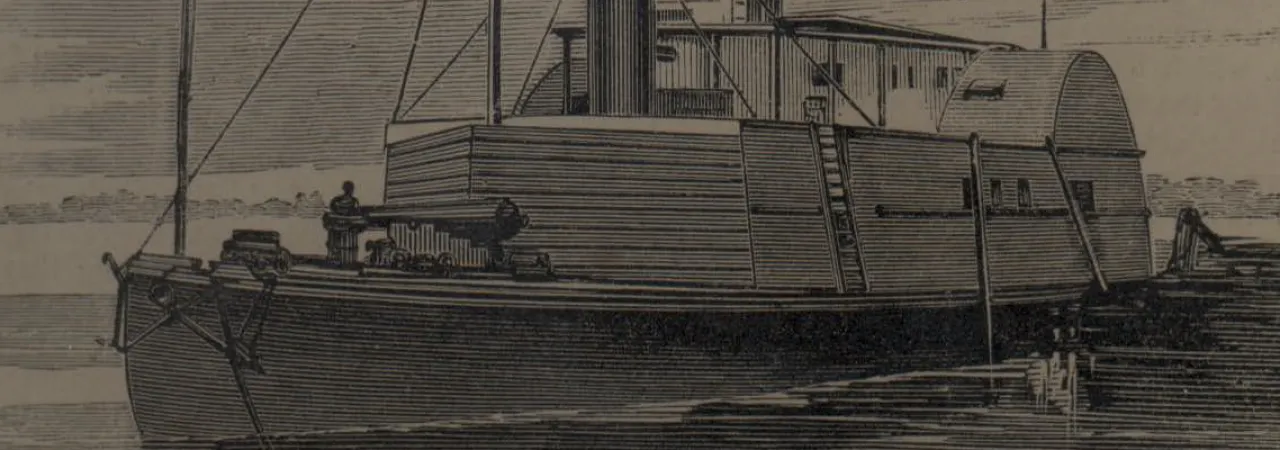

In April of 1861, war came to Charleston. The Confederate defenders of the city built an elaborate series of forts and batteries to defend the harbor. Many of them were placed on low-lying islands only reachable by boat. Keeping the men around the harbor fed and equipped was a constant requirement, so military commanders relied on boat traffic nearly continuously. That year, Smalls was hired onboard the Planter, a new, 147-foot long side-wheel steamship owned by John Ferguson, a wealthy Charleston ship owner and businessman. Ferguson leased the Planter to the Confederates to use around the harbor. By 1862, Smalls had worked in and around Charleston for ten years. Smalls’ skills were evident to the new white officers on the Planter, and he was relied upon to move the ship safely around the harbor. As the military fortifications grew, Smalls and the Planter ferried men, dispatches, supplies, and guns from the city to the forts and back again. Smalls watched carefully how the Confederates maintained their network of harbor defenses. He also took note of the increasing number of Union warships outside the harbor enforcing the blockade of Charleston.

Smalls was just one member of the Planter’s crew. The ship was captained by Charles J. Relyea, and the other white officers were first mate Samuel Hancock and engineer Samuel Pitcher. None of the three were from the South, nor were they Confederate Navy officers; they were merchant sailors hired as contractors and reported to Ferguson. Six other enslaved black men, two engineers, and four deckhands rounded out the Planter’s crew. Three of the six were owned by Ferguson, while the other three and Smalls were employed by other owners. For self-defense, Planter was armed with a 32-pound pivot gun on the bow and a 24-pound howitzer astern. Smalls and the other black crewmen would have been trained to use those guns if they were needed.

As Smalls watched the Confederates closely, events would convince him to make a bold move. On November 7, 1861, the Union navy captured Beaufort and the sea islands around the harbor of Port Royal. Although the town was damaged and most of the white plantation residents fled, Smalls was thankful to learn that his mother was safe among 10,000 now ownerless slaves. Smalls and his black friends also learned that the army established a new experiment there. The black residents were permitted to live together without white owners or overseers under the protection of the Union army and navy. They grew and sold cotton and other crops, and even built schools and acquired their own property. News of the progress of the settlements at Port Royal inspired the Charleston black community. Around that time, in March of 1862, Union Major General David Hunter, an abolitionist, took command of the Department of the South. On May 9, Hunter issued a military order freeing the slaves in Florida, Georgia, and South Carolina. Although his order was quickly rescinded by Abraham Lincoln as premature, Hunter began to recruit former slaves into volunteer infantry companies. Word of Hunter’s actions reached the slave community still under the thumbs of the Confederates in Charleston. It seemed clear to Smalls that wherever the Union military went, freedom would be there too.

Sometime in early May 1862, Smalls considered a bold plan to steal the Planter. First, any escape attempt would have to include the crew’s families; Smalls could not contemplate being separated from Hannah and the children if he was captured, and the other men were risking as much as he was. Second, although the Union army was in Beaufort 50 miles away, Union navy warships were just a few miles outside the harbor defenses that Smalls knew well. Third, the white officers of the Planter trusted the black crewmen to operate the ship, and they were in the habit of leaving overnight to be ashore with their families (in violation of orders from Confederate army commanders). Fourth, Smalls had learned the signals the ships used to communicate with the harbor sentries standing guard at the forts. Lastly, Planter frequently made trips to other ports, so her use of the outgoing ship channel was not uncommon. Smalls believed, at night, with a little bit of luck, he and the other black crewmen could make their escape.

Smalls put the plan into action on May 12, 1862. That afternoon, the Planter had returned from two weeks of setting up artillery on James Island. Smalls correctly predicted the officers would be tired and would leave the ship that evening. As the officers went ashore from the ship’s berth at the Southern Wharf, the crew banked the fires in Planter’s boiler and remained aboard. Smalls’ plan was to depart quietly in the pre-dawn hours and pick up the crew’s families at the North Atlantic Wharf on the Cooper River. Their departure time was tricky: leaving the city just before dawn would put them near the forts at first light, but Smalls knew if they were moving in the harbor in the darkness they would come under suspicion. They had one piece of luck: Smalls had learned that the guard boat, usually outside the harbor entrance, was under repair and would not be on station that evening. Sometime around 3:00 a.m., Smalls ordered the boiler fires relit and backed the Planter away from the wharf. Captain Relyea had left his favorite broad-brimmed hat on the bridge, and Smalls placed the hat on his head to impersonate the captain – at least from a distance. One armed sentry noticed the ship leaving, but no alarm was raised. Smalls moved the ship slowly up the Cooper River in the darkness and approached the North Atlantic Wharf. There, without tying up, the Planter quickly took aboard the women and children. Two women and three other men are known to the Planter’s crew also embarked. Except for Hannah, none of the women were told of the escape plan until the last minute. Slowly, Smalls turned the Planter around and headed for the channel.

Smalls and the other 15 men, women, and children onboard Planter were now runaway slaves, and the most dangerous part of their journey to freedom was still to come. As they left Charleston behind, Smalls hoisted the Confederate and South Carolina Palmetto flags from the Planter and ordered the women and children sent below. Soon, the ship came near Fort Johnson on James Island in the pre-dawn darkness, and Smalls passed close to a gunboat and a brig. As Captain Relyea would have done on any other morning, Smalls calmly gave the vessels a short salute from the Planter’s whistle and returned a wave with a cheery greeting. With dawn breaking to the east, the Planter approached the high brick walls and guns of Fort Sumter. The crewmen on the Planter nervously busied themselves on deck, their fates tied to Smalls’ next move. As the Planter neared, the sentries waited for the recognition signal. Smalls gave two long and one short blasts of the whistle: the proper signal for an outbound ship. The sentries happily waved the Planter on, and Smalls waved back from under Relyea’s hat.

They were not clear yet. As Smalls skillfully maneuvered through the chain of obstructions marking the outer harbor entrance, he could see the Union fleet ahead. Ordering up more steam, Smalls opened the throttle. He had successfully passed the Confederate guns, but the Planter could still be considered a threat by the Union warships. He hauled down the Confederate flags and hoisted a white bedsheet, possibly taken from Hannah’s hotel. Onboard the clipper ship USS Onward, the officers noticed the steamer hurrying out of the channel and sent their crew to battle stations before they noticed the makeshift white flag. Smalls pulled the Planter alongside and hailed the captain of the Onward: “Good morning, sir! I’ve brought you some of the old United States guns, sir!” The men and women on the Planter were free.

Congress granted prize money to Smalls and his crew, and the captured Planter was used for blockading duties. Smalls also provided Union commanders detailed knowledge of the Charleston defenses, including a signal flag codebook. Smalls was hired as a pilot for the blockading squadron, and in 1863 he was made captain of the Planter. After the war, Smalls returned to Beaufort and purchased his former master’s home. He ran a business and was elected to the South Carolina legislature. In 1874, he was elected to the U. S. House of Representatives and served two terms. Hannah died in 1883, and Robert Smalls died of malaria and diabetes in 1915. He was buried in Beaufort, and his gravestone is inscribed with a statement he made to the South Carolina legislature in 1895: “My race needs no special defense, for the past history of them in this country proves them to be the equal of any people anywhere. All they need is an equal chance in the battle of life.”

Further Reading

- Be Free or Die: The Amazing Story of Robert Smalls' Escape from Slavery to Union Hero By: Cate Lineberry

- War on the Waters: The Union and Confederate Navies, 1861-1865 By: James M. McPherson

- Iron Dawn: The Monitor, the Merrimack and the Civil War Sea Battle that Changed History By: Richard Snow

- Lincoln and His Admirals By: Craig Symonds

- The Civil War at Sea By: Craig Symonds