Originally not allowed to join the Army, by the end of the war, some 180,000 to 200,000 Blacks served in the United States Colored Troops (USCT) and comprised ten percent of the U. S. Army. There were at least 166 regiments of Black soldiers, who fought in approximately 450 battle actions and were instrumental in helping to win the Civil War and freedom for their people. As a result of their participation in the war, three amendments were added to the Constitution. The 13th that abolished slavery, the 14th gave Blacks equal protection under the law, and the 15th gave Black men the right to vote.

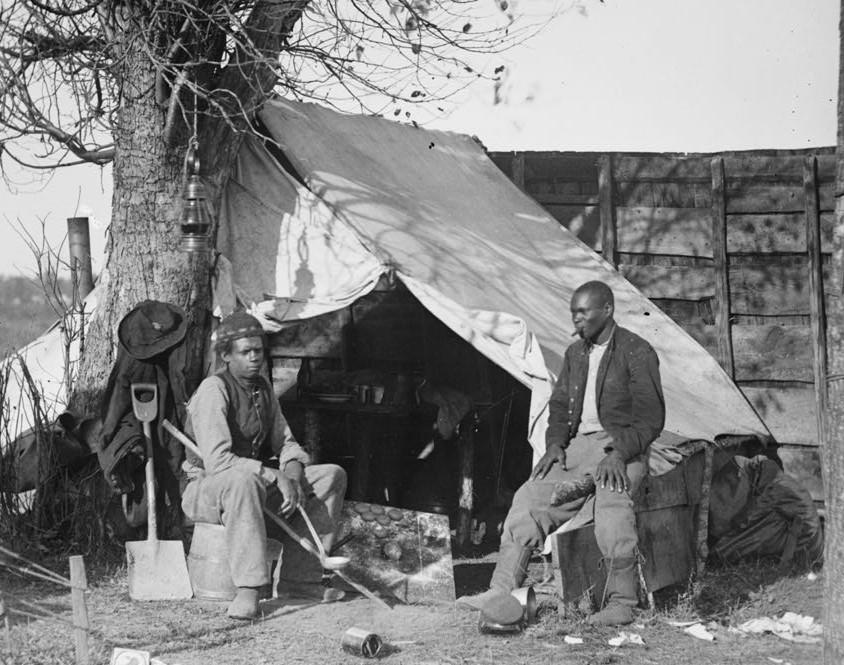

Throughout the war, the Union used thousands of Blacks as servants, teamsters, laborers, cooks, and in other support duties. These types of duties did not qualify them as soldiers. However, there are stories that state some of these men picked up arms and used them against their enemies. Some of these men may have joined the armies later in the war. For example, Sergeant Nimrod Burke of the 23rd USCT, started the war as a civilian teamster and scout for the 36th Ohio Volunteer Infantry in April 1861. These men earned positions as non-commissioned officers partially because they were familiar with the procedures of the army. There were also many slaves who had labored for the Confederate armies and escaped to the Union army, then became USCT soldiers.

While tens of thousands of Blacks served in the Union Army, they did not see the same service as the white counterparts. Many Black regiments were employed mostly in manual labor, utilized to do the work for white regiments, in order for those soldiers to concentrate on fighting. They were doing the same work as the Blacks who were paid as laborers, teamsters, and cooks. Other colored soldiers were used to guard forts, contraband camps, wagon trains, and prisoners of war. Many of the colored troops did see combat and many of their officers praised their conduct and bravery in the military actions, in which they participated.

The first Black troops to serve in the Civil War were actually enlisted in 1862. They were raised in Kansas, Louisiana, and South Carolina. On July 17, 1862, the Second Confiscation and Militia Acts were approved and subsequently signed by President Lincoln. These acts allowed as many persons of African descent as necessary to be “employed to help suppress the rebellion and use them “in such manner” as he may judge best for public welfare.” To some, this meant that they could be used as soldiers.

In Louisiana in July 1862, General John Phelps began to recruit Blacks (the Louisiana Native Guard militia) to reinforce his troops outside of New Orleans; General Benjamin Butler could not authorize General Phelps to do this. Phelps resigned. Less than a month later, General Butler fearing an attack on New Orleans asked for reinforcements, being turned down, he organized three regiments of the Louisiana Native Guards. The members of the Guard actually approached Butler first and confirmed their loyalty to the Union on August 15th. Butler allowed them to keep their Black officers, 1st and 2nd regiments had Black captains and lieutenants, and the 3rd had Black and white officers. General Butler changed their name to the Corps D’Afrique. Later in the war, their designations will be changed to USCTs. These three regiments became the 73rd, 74th, 75th USCTs.

In Kansas, a paragraph in the Daily Conservative of October 6, 1861, described Senator James H. Lane’s cavalrymen as such: “One peculiarity of this mounted force is curious enough to be noted down. By the side of one doughty and white cavalier rode an erect well-armed and very black man: his figure and bearing were such that, without any other distinguishing characteristic he would still have been a marked man...this is the first instance which has come to our personal knowledge – although not the only one in fact – of a contraband serving as a Union soldier.” This was in the fall of 1861 and Kansas employed Black soldiers, but they had come through the fighting during the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854 up until the Civil War. Officially, now General Lane organized the 1st Kansas Colored Infantry on August 5, 1862, with his notification to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton. The next day, he wired Stanton again stating that he was raising his regiment based on the Second Confiscation Act. The 1st Kansas had the distinction of being the first colored troops to engage the enemy in October 1862 with a raiding party in Missouri. They later became the 79th USCT (new).

In South Carolina, General David Hunter had organized a regiment of South Carolina former slaves, the 1st South Carolina Colored Infantry only to have them disbanded because President Lincoln would not approve of Hunter’s emancipation of the slaves in his military district nor authorize the raising of Black troops. While Hunter failed, orders were addressed to General Rufus Saxton on August 25th, 1862 to raise 5,000 Black soldiers. The 1st South Carolina was reformed, and they later became the 33rd USCT. The importance of this order was that these soldiers were raised by the authority of the United States War Department and not by some enterprising general on his own authority.

On September 22, 1862, President Lincoln issued the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation to take effect on January 1, 1863. The emancipation freed slaves in the Southern states still in rebellion against the United States. The actual emancipation allowed for the enrollment of freed slaves into the United States Army, which allowed some 200,000 Blacks to serve in the army.

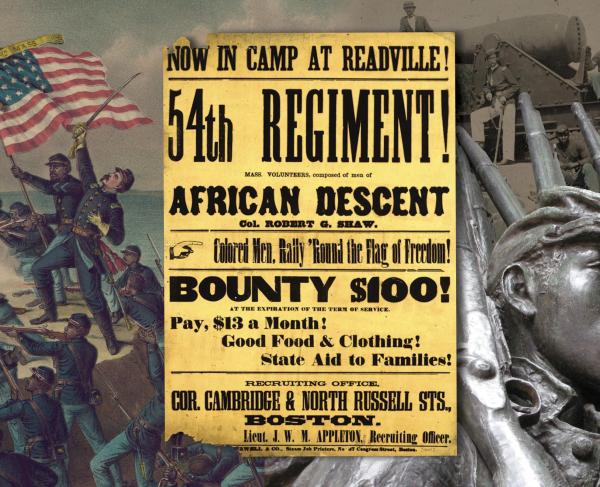

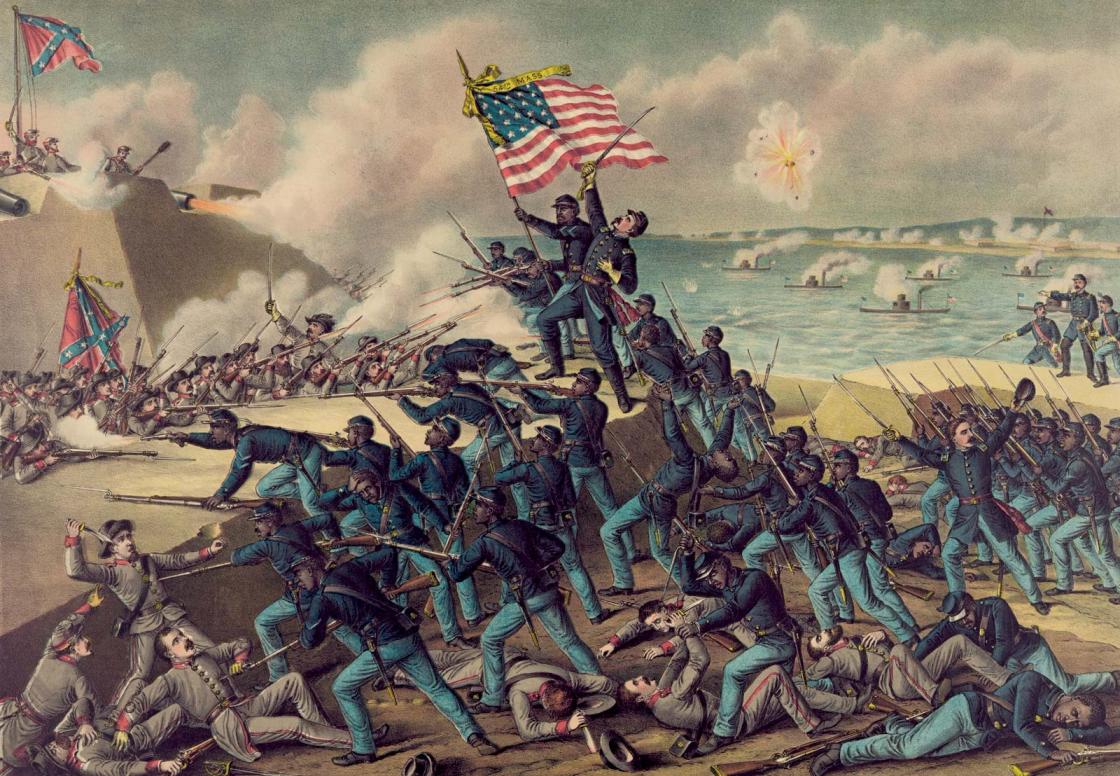

The 54th Massachusetts Infantry Colored was raised from many states in the North. They are the most famous Black regiment, as the movie Glory was based on their story. They were authorized in March 1863 by Governor John Andrew and Colonel Robert Gould Shaw was their commander. Shaw’s parents were abolitionists as was Shaw and most of the officers. The soldiers were recruited by abolitionists including Frederick Douglass, perhaps the greatest African American personality in the 19th century – he sent his two sons to the 54th. They were mustered into service on May 28, 1863, however, so many recruits enlisted that the overflow created two more Massachusetts regiments, the 55th Infantry and the 5th Cavalry. The overwhelming majority of the recruits for these three regiments were educated men. The 54th is most renowned for spearheading the attack on Fort Wagner on July 18, 1863. The 54th and some white units took the outer walls of the Fort but could not take the fort. Colonel Shaw and 271 of his men were casualties. Sgt. William H. Carney received the Medal of Honor for grabbing the U.S. flag taking it to the enemy ramparts and bringing it back, even though he was severely wounded.

They, like all colored soldiers, were involved in the pay controversy, where white troops were paid $13 a month but Black troops were paid only $10 a month with $3 withheld as a clothing fee making their pay $7 a month. On September 28, 1864, pay was equalized by the Congress and they received 18 months’ pay from the time of their enlistment. Only free men were given back pay, the slaves were not given back pay at the higher rate. This controversy affected the entire USCT. The 1989 Academy Award-winning movie Glory re-established the now-popular image of the combat role of African Americans played in the Civil War.

There were only four state regiments who kept their state designations throughout the war; all of the others became regiments in the USCT. The 54th Massachusetts Infantry Colored, 55th Massachusetts Infantry Colored, 5th Massachusetts Cavalry Colored, and the 29th Connecticut Infantry Colored were part of the USCT with state designations. For example, state regiments like the 1st North Carolina Colored Infantry (U.S.) became the 35th USCT.

The actual order creating the Bureau of Colored Troops was General Order number 143 issued on May 22, 1863. By the end of the war, 166 regiments of infantry, cavalry, heavy artillery, engineers, and light artillery served and constituted one-tenth of the army. While the U. S. Navy was integrated throughout the war and between 10,000 and 20,000 African Americans served as sailors. Approximately 38,000 to 43,000 died, another 30,000 plus were wounded, and most deaths were caused by disease. There were some prominent African American recruiters for the Union army including John Mercer Langston, William Wells Brown, and Frederick Douglass. Douglass’ memorable quote about Blacks fighting in the Civil War was:

“Once let the black man get upon his person the brass letters U.S.; let him get an eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulder, and bullets in his pocket, and there is no power on the earth or under the earth which can deny that he has earned the right of citizenship in the United States.”

In the greater Fredericksburg area, the first Black troops to fight General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia was the 23rd Regiment of the United States Colored Troops. During the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House, on May 15, 1864, the 23rd was called on to help the 2nd Ohio Cavalry hold off General Thomas Rosser’s Cavalry brigade. They marched from the Chancellorsville ruins for two miles and pushed back Rosser’s brigade. It was a minor skirmish, but it gained a lot of respect from the white troops who cheered their actions. This proved to the white soldiers know that Blacks would fight when given the opportunity.

The Battle of Wilson’s Landing or Wilson’s Wharf on May 24, 1864, in Virginia, pitted 900 men of the 1st and 10th USCT, and two cannon from battery M of the 3rd NY Light Artillery, under General Edward Wild, against a force of 2,500 Confederates under General Fitzhugh Lee, General Robert E. Lee’s nephew. After Lee drove in the Union pickets, he sent in a flag of truce demanding the surrender of the garrison, but general Wild declined the offer by saying, “We will try it.” A transport landed 150 unarmed white soldiers and the gunboat USS Dawn helped the Union forces. General Lee ordered a charge, but the garrison proved too strong and Lee retreated. Union casualties were less than 50 and Confederate casualties ranged from 175 to 200.

The USCT fought in major battles, as well, Vicksburg, Petersburg, Richmond, Nashville, Fort Fisher, and Appomattox. In December 1864, the African American division in the Army of the Potomac was joined with the two African American divisions in the Army of the James to form the XXV Corps – the only Black Corps in the Civil War. This was the largest grouping of Black soldiers in the war. After the war, they were sent to Texas and included in the 50,000 man U. S. Army commanded by General Philip Sheridan.

General Benjamin Butler appeared before Congress in 1874, advocating the passage of a bill giving civil rights to the Negro race. He gave an eyewitness account of the fighting at New Market Heights and then said of the dead:

“…I looked on their bronzed faces upturned in the shining sun as if in mute appeal against the wrongs of the country for which they had given their lives, and whose flag had only been to them a flag of stripes on which no star of glory had ever shone for them-feeling I had wronged them in the past, and believing what was the future of my country to them-among my dead comrades there I swore to myself a solemn oath: “May my right hand forget its cunning, and my tongue cleave to the roof of my mouth, if I ever fail to defend the rights of those men who have given their blood for me and my country this day and for their race forever;” and, God helping me, I will keep that oath.”

Further Reading:

- A Slave No More: Two Men Who Escaped to Freedom, Including Their Own Narratives of Emancipation By: David W. Blight

- A Brave Black Regiment: The History of the Fifty-Fourth Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry 1863-1865 By: Capt. Luis F. Emilio

- Slavery and the Making of America By: James Oliver Horton and Lois E. Horton

- Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era By: James M. McPherson

- The Negro's Civil War: How American Blacks Felt and Acted During the War for the Union By: James M. McPherson

Related Battles

8,150

3,236

1,057

1,900

18,399

12,687