Shiloh: Scene of Battle. Kurtz and Allison lithograph from 1886 depicting the ferocity of fighting.

January 9, 1861, was a momentous day for the 100 men gathered at the State House in Jackson, Miss. They were delegates to the Mississippi Secession Convention, and they were about to make a fateful decision — not just for their state but also for themselves personally. Some were wealthy planters who owned large plantations along the Mississippi River; they knew full well that secession would lead to war, and that war would, at minimum, lead to closed markets and, potentially, total destruction. While dedicated Mississippians, they were still unenthusiastic about secession and termed “cooperationists” as they tried to delay disunion. Others, however, were more adamant about immediate secession, and they carried the day. The final vote was a dominating 84 percent majority for leaving the Union, and there was an immediate feeling of consequence when the deed was done. While casting his vote, James L. Alcorn explained, “The die is cast — the Rubicon is crossed — and I enlist myself with the army that marches on Rome. I vote for the ordinance.”

The delegates must have understood the significance of their action, but few realized the extent to which they would be personally involved. Most who were of military age, and a few who were not, opted to join the newly established ranks during the excitement of secession and war, but the extent to which they would be called on to suffer and perhaps die was probably not foremost in their minds. It has often been noted that the signers of the Declaration of Independence in 1776 were potentially signing their death warrants; the same could be said of the Mississippi delegates in Jackson. For some, their actions would consign them to death. Others would suffer terrifying wounds or imprisonment. Most would be economically and socially dispossessed. Their state would be devastated. It was a serious decision to make.

Although a third of the delegates were too old to serve in the ranks (many still equipped companies from their locales or sent sons to the war effort), there were numerous delegates to the secession convention in the Confederate army by April 1862. During the initial year of the war, these delegates experienced only limited exposure to the conflict. There was some suffering, to be sure — the first delegate died in September 1861, but it was not on a battlefield or even in the army. Others were removed from Mississippi to defend other parts of the Confederacy. At least 15 of the delegates, primarily those who joined up first, were sent to the Virginia front, serving far from home in the Eastern Theater.

War Comes Home to Mississippi

The war began to come closer to Mississippi in February 1862, when a Union army under Ulysses S. Grant won impressive victories at Forts Henry and Donelson in northwestern Tennessee. This fighting, uncomfortably close to Mississippi itself, led to the first death of a delegate in action. Francis Marion Rogers of Monroe County, a wealthy lawyer, planter, judge and captain in the 14th Mississippi Infantry, died defending Fort Donelson on February 15. Beyond Rogers, at least four others who had been at Fort Donelson were either wounded or sent to Northern prison camps. Then the news became much worse: multiple Union armies were moving south toward Mississippi, intent on capturing the vital Confederate railroad crossing at Corinth in the northeastern corner of the state. The war was about to hit Mississippi itself.

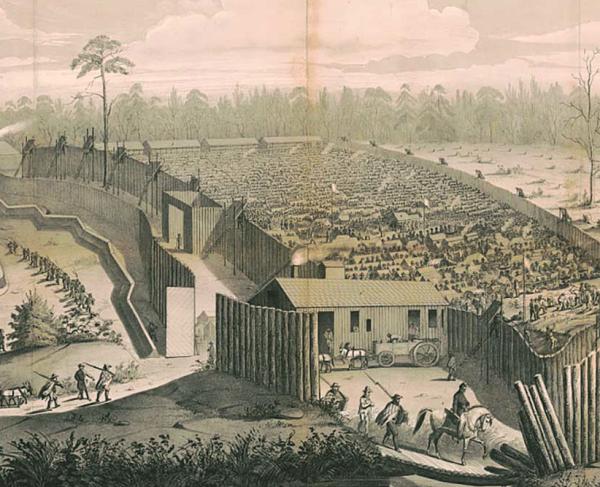

At least eleven delegates were a part of the army assembling at Corinth under Gen. Albert Sidney Johnston, who soon advanced across the state line into Tennessee to attack Grant’s army at Pittsburg Landing. He hoped to destroy that army before another Federal force under Don Carlos Buell arrived on the scene. In effect, Johnston was trying to defend Corinth, her railroads, the state of Mississippi and the Mississippi Valley as a whole by going on the offensive. The result was the climactic Battle of Shiloh, fought April 6–7, 1862.

Of the 11 former delegates at Corinth, 10 saw action at Shiloh. The exception was lawyer and future Confederate Brig. Gen. Samuel Benton of Marshall County, who was detached from his regiment, the 9th Mississippi, in order to form a new unit in the interior of the state as early as March 24. The rest, however, went into the fight at Shiloh. On all, the battle would have a tremendous impact; for some, it would mean life or death.

To Shiloh

All 10 delegates engaged in literally defending Mississippi at Shiloh were officers, as would be expected given their status in the community and the early Confederate practice of the men electing their own officers. Four were captains of companies, with another captain acting as a staff officer to Confederate Maj. Gen. Braxton Bragg. There was also one major, two lieutenant colonels, one colonel and a brigadier general.

When the Battle of Shiloh began at dawn on April 6, these 10 were arrayed throughout the Confederate army, which was stacked in line four corps deep. The only delegate in the first line, Maj. Gen. William J. Hardee’s corps, was Col. John J. Thornton, commanding the 6th Mississippi Infantry in Brig. Gen. Patrick Cleburne’s brigade on the extreme left flank. Thornton himself was somewhat of an anomaly; representing Rankin County in the convention, the doctor was so convinced that he should represent the intentions of his cooperationist constituents that he voted against secession and did not attend the convention on January 15, the day the ordinance was officially signed. Thus, he became one of only two delegates who did not sign the ordinance. The other was a delegate who attended only the first three days of the convention, not long enough to cast a vote on the secession ordinance — making Thornton the only active participant in the convention who refused to sign. Yet, he was one of the first delegates to take up arms for the Confederacy, having been a militia officer before the war.

Thornton led his Mississippians forward on that bright morning, but Cleburne’s brigade soon ran into a swamp. The quagmire was so extensive around Shiloh Branch that it forced the brigade to split and go around on either side. Most of the regiments went to the west of the swamp, attacking at Shiloh Church, but Thornton’s 6th Mississippi and the 23rd Tennessee went east and entered Rhea Field, where the 53rd Ohio was waiting.

The result may sound like the stuff of legend, but it is true. Thornton and his Mississippians made three unsuccessful assaults across Rhea Field and through the enemy’s encampments, and were each time driven back by the Ohioans and an Illinois artillery battery on their flank. The regiment lost 300 of its 425 men on that one field, its colonel among the wounded. As Thornton led his men forward during one of the assaults, the regiment’s flag bearer was hit and instantly killed. Thornton grabbed the flag and continued on, but he too was quickly cut down, severely wounded in the thigh. The Battle of Shiloh was over for this man, wounded in defense of the secession for which he would not vote.

Forward the Mississippi Brigade

Thornton and his Mississippians’ experiences were similar to those of the other units in Hardee’s first line. Few of them made much progress for several hours, necessitating the Confederate high command to send forward the next wave of troops, Maj. Gen. Braxton Bragg’s corps. In this line were numerous Mississippi convention delegates, including one of Bragg’s staff officers, assistant adjutant general Harvey W. Walter, a lawyer from Marshall County. Little is known of Walter’s experience at Shiloh, but Bragg’s official report, written later in April, commended him for his service.

The other Mississippians in this second line were all in one brigade, Brig. Gen. James R. Chalmers’s Mississippi brigade on the extreme right. The commander, a lawyer and large planter before the war, had attended the secession convention as a delegate representing DeSoto County. After the convention, Chalmers had enlisted as a captain, but was named colonel of the 9th Mississippi just one month later. By the Battle of Shiloh, he had risen to brigadier general in command of a brigade. Within the brigade, Lt. Col. Hamilton Mayson, a lawyer from Marion County, was commanding the 7th Mississippi in the absence of its colonel. There were also two former delegates serving as captains: small farmer John B. Herring of Pontotoc County commanded a company in the 5th Mississippi, while Daniel H. Parker of Franklin County — who, like Thornton, had initially voted against secession but quickly joined the Confederate army — commanding a company under Mayson in the 7th Mississippi. Company E, 7th Mississippi was thus inundated by secession convention delegates; its captain had been there, as well as its regimental commander, brigade commander, and an officer on its corps commander’s staff.

Chalmers’s brigade moved forward in support of the Confederate right near Spain Field and aided the front line units, most notably Brig. Gen. Adley Gladden’s brigade, in pushing Federal Brig. Gen. Benjamin Prentiss’s division back. Thereafter, when the Confederate high command realized there was a major threat farther to the right, Chalmers’s Mississippians and an Alabama brigade were taken out of line and redirected to the east, where they soon fought Col. David Stuart’s Federal brigade in the ravines near the Tennessee River. Casualties were numerous as they fought their way up and down the slopes, but none of the convention delegates were hit.

The Confederate advance stalled on this right flank, however, as it had begun to do all across the field, necessitating the Confederate high command to throw in additional units. Maj. Gen. Leonidas Polk’s corps, the next in line, contained no Mississippi convention delegates, but the reserve corps commanded by former U.S. vice president John C. Breckinridge contained four more. Lawyer, planter and future Confederate general William F. Brantley of Choctaw County, the major of the 15th Mississippi, was in command of the regiment, while its colonel, Winfield S. Statham, led the brigade. Prewar lawyer Francis Marion Aldridge of Yalobusha County was a captain serving under Brantley. Edward F. McGehee, who owned a large plantation with more than 70 slaves in Panola County, was lieutenant colonel of what was originally the 25th Mississippi but had been recognized as the 2nd Confederate Infantry. Brantley and Aldridge were in Col. Winfield Statham’s brigade, while McGehee was assigned to Brig. Gen. John S. Bowen’s brigade. In addition, planter Thomas D. Lewers of DeSoto County was a captain in Col. William Wirt Adams’s cavalry regiment assigned to this reserve corps, but the troopers saw little action, their main job being to hold a ford on Lick Creek to the south.

As Chalmers, Mayson, Parker and Herring pushed forward to the east near the Tennessee River, Statham and Bowen led their brigades into the gap that had been created earlier, when the Mississippians and Alabamians were removed from the line. They took position on the south side of a large cotton field, with a peach orchard and a small pond on the northern fringes. They were led by an impressive array of officers, including army commander Gen. Albert Sidney Johnston, former vice president Breckinridge, and Tennessee governor-and-Confederate staff officer Isham G. Harris.

To the Banks of the Tennessee

The famous assaults across Sarah Bell’s cotton field and the Peach Orchard ultimately succeeded, but at a terrific loss of life, including Johnston. Death and injury also came to the Mississippi delegates. In these assaults, Lt. Col. McGehee was terribly wounded in the left foot while, in the words of his regimental commander, John D. Martin, “gallantly encouraging his regiment, without regard to his personal exposure.” Brantley likewise was wounded while leading the 15th Mississippi onward. Both would survive, but Francis Marion Aldridge was not so fortunate. Hit while leading his company forward in the attacks, Aldridge was killed that day.

The Mississippi delegates’ participation continued in the assaults throughout the remainder of the first day’s action. With so many down, the only major unit containing delegates still in organized operation was Chalmers’ Brigade. Chalmers, Mayson, Parker, and Herring thus led their men forward on the extreme right flank of the army, up and down the massive ravines near the Tennessee River. After aiding in the capture of the remnants of the Hornets’ Nest defenders, their final action came near sundown when they attempted to assault Grant’s final line of defense near Pittsburg Landing. Faced with artillery, infantry, gunboats and the leading elements of Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell’s reinforcing army arrayed in this final Union line, the Mississippians’ hope of breaking through was futile. They retired out of artillery range for the evening, although the Union navy’s big guns peppered them throughout the night.

It must have been a miserable night for all the delegates, especially Brantley, Thornton and McGehee, all wounded terribly during the fighting. The non-wounded huddled helplessly as the naval guns and heavy rains bombarded them. Only the lifeless corpse of Francis Marion Aldridge rested peacefully that night.

Had the Mississippians and the Confederate high command known what was coming the next day, they would have been even more uncomfortable. Grant and Buell counterattacked at dawn, driving the weakened Confederates backward throughout the second day’s fight. With most of the delegates not in Chalmers’s brigade killed or wounded, only those in Chalmers’s unit fought together as a group on the second day. They resisted the Union advances on the Confederate right near the famous Peach Orchard until Confederate commander Gen. P. G. T. Beauregard, having taken over for the fallen Johnston, realized the futility of further resistance. The delegates thus began the slow march back to Corinth. A company of Wirt Adams’s cavalry regiment was engaged the next day in combating the dismal Union pursuit, but Thomas Lewers’s men were apparently not engaged.

Never More Worthy of their State

These Mississippi delegates, as well as thousands of other Southerners, had attempted to defend Corinth, her railroads and the state of Mississippi with a bold stroke. Now, with one of those delegates dead and three others wounded, the remainder prepared to resist the further Union advance toward Corinth. That came in May, and the healthy delegates, as well as an infusion of others who were part of regiments just then joining the army, unsuccessfully attempted to stop the Union progression. Although that attempt likewise failed, the war went on. Vicksburg would be the next major Union goal, and many of the delegates engaged in that campaign as well.

For three of the 10 delegates at Shiloh, the Civil War was over. Aldridge was eventually returned to his native Yalobusha County and buried. Thornton and McGehee, the two most dreadfully wounded at Shiloh, resigned and returned home. Thornton later dabbled in the militia but was not able to take the field again. McGehee noted that he was “now a cripple and will be more or less so for life.” A fourth, Daniel H. Parker, fell sick in May 1862 and returned home to Franklin County, dying of typhoid fever on May 12.

As for the others, they continued in military service, with most rising in their respective ranks throughout the war. Chalmers continued to serve with distinction, particularly alongside Forrest’s cavalry. Braxton Bragg reported that at Shiloh Chalmers had been “at the head of his gallant Mississippians, [and] filled — he could not have exceeded — the measure of my expectations. Never were troops and commander more worthy of each other and of their State.” Brantley recovered from his wounds and served with distinction throughout the war, rising to the rank of brigadier general and commanding his brigade during the Franklin-Nashville Campaign. Herring and Lewers eventually rose to the rank of lieutenant colonel. On the other hand, Hamilton Mayson was driven from the army by Braxton Bragg in May, despite his superior Chalmers’s notation that he and the other commanders were “conspicuous in the thickest of the fight” at Shiloh.

For those 10 Mississippi delegates at Shiloh, despite giving their all for her defense, their state was now the war zone. Voting for secession — or not, in the cases of Parker and Thornton — had been the easy part. When it came to fitting action to their words, however, they were just as resolute and willing to lay their lives on the line. And all suffered for it, some even being wounded dreadfully and unable to return to the war. And then there was Francis Marion Aldridge, who had literally signed his death warrant by putting his signature on the Mississippi ordinance of secession.

Learn More: The Western Theater

Related Battles

13,047

10,669