The Battle of Gettysburg transformed the lush fields and bustling streets of the Pennsylvania town into a bloodstained hellscape in only three days. Having just witnessed the bloodiest battle in American history, the citizens of Gettysburg now faced the daunting task of dealing with its cost to their community. Splintered trees and fences littered the fields along with abandoned wagons, caissons, and cannons. Bullets and artillery shells scattered the ground, while dead horses and animals lay mangled among the trampled wheat and grass. “Everything that the carnage of battle could produce was evident,” remembered Gettysburg teenager Daniel Skelly.

But most of all, the armies left behind nearly 7,000 of their dead and thousands more wounded for the citizens of Gettysburg to care for and bury. As the Confederate army slipped away after the battle, Union soldiers formed burial parties to help identity and inter both friend and foe. However, on July 4, 1863 torrential rain unearthed shallow graves while the bodies left unburied began to decay under the sweltering heat that followed. The Union army departed Gettysburg on July 6 leaving the remaining burials to citizens of Adams County.

Following the armies' departure, Gettysburg’s population continued to swell with visitors. Friends and families of soldiers travelled to discover the fate of their loved ones. Others tended to their wounded brothers, sons, and fathers. The United States Sanitary and Christian Commissions arrived in Gettysburg to distribute supplies and clothing to the soldiers. Churches, schools, and houses harbored the sick and wounded until Camp Letterman general hospital opened outside of town on July 20.

As time and the elements uncovered makeshift graves and the death toll continued to rise, Gettysburg residents called for a solution. Evergreen Cemetery gatekeeper Peter Thorn advertised plots for reburials from his post in the 138th Pennsylvania while his pregnant wife Elizabeth remained in Gettysburg to bury them. However, other Gettysburg citizens sought to appropriate land for a separate cemetery—one devoted as a final resting place for the Union soldiers who gave their lives in defense of the nation.

Gettysburg lawyer David Wills brought this proposition to Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Curtain soon after the battle. Wills proposed a state funded cemetery on the eastern slope of Cemetery Hill. Governor Curtin formed a committee and appointed Wills as his personal agent for the establishment of the cemetery. Eventually, the committee purchased a 17-acre piece of land adjacent to Evergreen Cemetery that overlooked the fields of Pickett’s Charge.

Interments began on October 27, 1863. Wills contracted a handful of local African Americans responsible for disinterment and reburial overseen by former Gettysburg photographer Samuel Weaver. Weaver ensured his workers placed each body in a wooden coffin and collected any personal items they found to be claimed by relatives. When he completed his task the following year, Weaver catalogued a total of 287 personal effects found by his crew as they recovered the bodies.

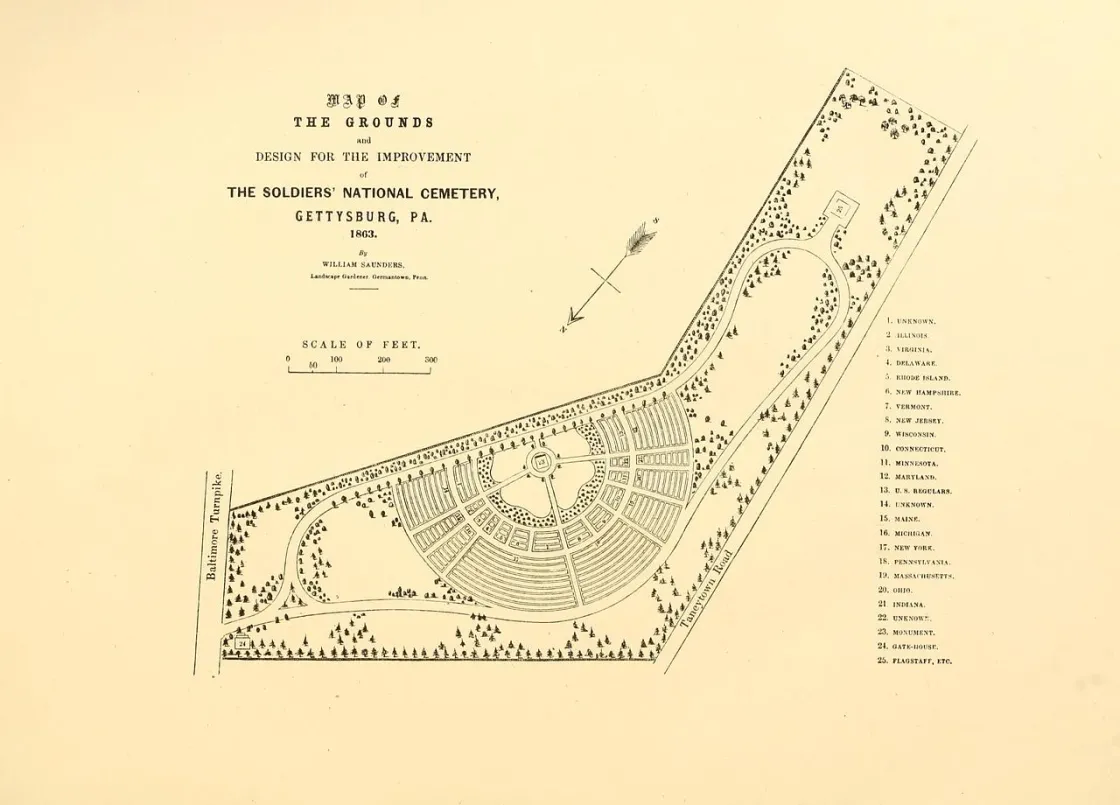

The committee chose landscape architect William Saunders to design the cemetery. He envisioned the cemetery as a nicely groomed park, with neatly cut grass and winding walkways. Saunders desired the graves to be arranged in a semi-circle surrounding a soldiers’ monument at the center and left room for various decorative trees and shrubbery. Wills and the committee decided each section should contain soldiers of the same state—with larger states toward the back and smaller states closer to the monument. Because Gettysburg lay on Northern soil, the national cemetery only contained Union dead. The Confederate fallen at Gettysburg were later relocated to Southern cemeteries in Virginia, Georgia, and South Carolina.

As Saunders and his crew continued reinterment, David Wills began organizing a ceremony to dedicate the new Soldiers’ National Cemetery. He and the committee chose Edward Everett, a Massachusetts politician and gifted orator, to deliver the keynote address at the dedication on November 19, 1863. Wills also extended an invitation to President Abraham Lincoln to provide “a few appropriate remarks” during the ceremony. The president agreed and departed for Gettysburg on November 18 to attend the dedication the following afternoon. Though Lincoln’s busy schedule permitted him little time to attend gatherings of this nature, he determined the ceremony important enough to attend.

Lincoln arrived in Gettysburg at approximately 6 pm on November 18, 1863, after a few stops in Baltimore and Hanover where the president briefly appeared to a few small crowds. A small entourage accompanied him, including his personal secretaries John Hay and John Nicolay and three cabinet members: Secretary of State William Seward, Postmaster General Montgomery Blair, and Secretary of the Interior John P. Usher. A contingent of foreign ministers and a military escort also travelled to Gettysburg with Lincoln. As the president stepped off the train, a cluster of citizens and reporters followed him down from the station to the David Wills house where Lincoln spent the night.

Lincoln probably began to write his “appropriate remarks” shortly before he left Washington, for the president’s busy schedule likely permitted him little time to write after he arrived. He met with David Wills to discuss last minute details of the ceremony while a crowd in the town diamond serenaded him by singing “We Are Coming, Father Abra’am.” The president awoke the next morning to brisk weather and overcast skies. John Nicolay entered the president’s room to find Lincoln placing the finishing touches on his address.

At 9:30 am, the president mounted a chestnut bay horse and joined the procession down Baltimore Street. A marine band greeted the dignitaries on Cemetery Hill where nearly 15,000 people awaited them. Reverend T.H. Stockton began the ceremony by offering a benediction, during which the clouds parted and gave way to a bright blue sky. Then, Edward Everett stood to deliver his keynote oration. He spoke for nearly two hours, describing in detail the events of the battle and war as well as relating it to the ancient Greeks and Romans.

After a brief musical interlude, Lincoln rose from the speakers’ platform to deliver his Gettysburg Address. The speech lasted only two minutes, but Lincoln spoke some of the most important words in American history. However, the president's address garnered mixed reactions from contemporary audiences after the ceremony. Republican newspapers praised it, while Democratic presses criticized it. Edward Everett wrote Lincoln the following day to commend the president for his speech. "I should be glad if I could flatter myself that I came as near to the central idea of the occasion, in two hours," Everett confessed, "as you did in two minutes." Following the dedication, Lincoln departed for Washington at 6 pm, completing his 25 hour stay in Gettysburg

Samuel Weaver's crew finally finished burying the dead in 1864, but the National Cemetery did not reach completion until July 1, 1869 when a similar ceremony dedicated the Soldiers’ National Monument. This time, Major General George Gordon Meade—the hero of the Battle of Gettysburg—served as the keynote speaker. In 1872, the Federal government took stewardship of the cemetery and now it remains in the hands of Gettysburg National Military Park. Of the 3,354 bodies buried in the Soldiers’ National Cemetery, 979 are unknown. Now, the cemetery serves as the final resting place 6,000 individuals who “gave the last full measure of devotion” in not only the Civil War but five additional American conflicts.

We're on the verge of a moment that will define the future of battlefield preservation. With your help, we can save over 1,000 acres of critical Civil...

Related Battles

23,049

28,063