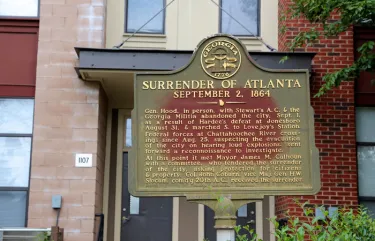

Surrender of Atlanta

Stephen Davis

Before noon on September 1, army headquarters downtown had issued orders for the withdrawal of the three infantry divisions (Stewart's corps) still in Atlanta, along with the Georgia militia, all heading out the McDonough Road south to join Lt. Gen. Hardee's and Lt. Gen. S.D. Lee's corps. Gen. Hood, having remained at his Atlanta headquarters, rode among the retreating columns; much of his headquarters baggage had to be burned for want of wagons to haul it. Panicked civilians, dreading the Yankees's occupation of the city, attached themselves to the retreating Southern columns.

Before they left, Confederate soldiers threw open the army's commissary warehouse for civilians to take whatever they wanted.

Stewart's infantry started marching out of the city around 5 p.m. What cannon that could not be brought out were spiked. That night Brigadier Samuel Ferguson's cavalrymen and Georgia militiamen wrecked the five locomotives and burned the eighty freight cars that had not gotten out of the city before the Yankees cut the Macon railroad. Twenty-eight cars were filled with ammunition; set afire, their explosions were so loud that Gen. Sherman at Jonesboro claimed to have heard them.

At the Chattahoochee, Maj. Gen. Henry W. Slocum, who assumed command of the Twentieth Corps following Gen. Hooker's resignation, also heard the explosions. He ordered a recon patrol be sent out from each of his three division at dawn. Mayor James Calhoun recognized the benefit to the public order if Federal military control was quickly established in the city. With Confederate authorities gone, he accepted the responsibility of surrendering Atlanta and trying to safeguard the city's remaining citizens and their property. Calhoun met with Gen. Ferguson and learned that he and his troopers would leave the city after 11 a.m.

Calhoun then assembled a group of eight prominent Atlantans and rode out Marietta Street to meet the Federals, who would be coming from that direction. They ran into a column sent out by Ward's division, commanded by Col. John Coburn. "Colonel Coburn, the fortune of war has placed Atlanta in your hands," Calhoun remembered saying. "As Mayor of the City I come to ask your protection for noncombatants and for private property." Calhoun said that Ferguson's cavalry were leaving and that the Federals could enter the city at once. He wanted a quick establishment of Union authority to prevent looting by the lawless elements. Coburn complied, and sending work to both Generals Ward and Slocum, marched into Atlanta.

The first Union infantry entered after noon with flags flying and bands playing. Reaction from the several thousand residents still in the city was mixed. Southern sympathizers looked on sullenly, powerless to even jeer. Northern sympathizers, "secret Yankees," were of course warmer. Riding in on the evening of September 2, General Williams heard a woman call out, "Welcome!" African-Americans, former slaves, were most effusive. "Bress de Lord," a Massachusetts soldier heard some cry. "De Yanks am come, yah! Yah! Yah!"

The sounds of Hood's train-demolition on the night of September 1-2 alerted Sherman that the city was being abandoned by the Rebels. During the 2nd, confirming messages came to his headquarters, so he was able to telegraph Washington: "Atlanta is ours and fairly won."