One of the most striking images from the lead up to the American Revolution is the image of tax collectors and loyalists being tarred and feathered by American patriots. While tarring and feathering had been used as a form of public punishment and ridicule in Europe since the Middle Ages, it became most famous for its use in colonial America in the 1760s and 1770s.

Tarring and feathering was usually used as a form of vigilante justice and became a favorite of early American patriots in their protests against British taxation. Tax collectors, customs officials, or avowed loyalists were apprehended by a crowd or mob of colonists to be publicly punished and humiliated. First, they would strip the person of their clothes. Usually, they would only strip off their shirt, but sometimes they would be stripped of all their clothes. Next, they would pour or brush hot pine tar all over their body. Pine tar was frequently used by sailors in port towns for water-proofing ships and sails. This pine tar was not as hot as modern petroleum-based tar when heated, but it would often blister or burn the skin. While pouring the tar on their skin was extremely painful, the punishment was not meant to be deadly, and no one was known to have been killed as a result of tarring and feathering. They would then cover this tar with feathers, resulting in the person having the humiliating appearance of a chicken or large bird. On at least one occasion the colonists lit the feathers on fire to burn the skin underneath. The person would then often be placed on a cart or forced to sit of a wooden rail and then would be paraded through the streets of the town to make a mockery of them. Occasionally, a sign would be fashioned that would explain why the person was being punished and they would often be struck or whipped as well. As awful as a punishment it was to be tarred and feathered, crowds and individuals would often use it as a threat. The threat of having to endure such treatment proved to be a powerful tactic of intimidation.

This punishment had been used on criminals in colonial America, but it was quickly adopted by the Sons of Liberty in the 1760s as a preferred punishment on tax collectors and customs officials. The Sons of Liberty was a secret organization, so how organized or planned the events were continues to be a matter of question. In response to the passage of the Townshend Acts the punishment was used by patriots to ensure that their boycotts of British goods were not violated. It proved to be an effective way of making a public spectacle of those who (against the desire of Whigs and the Sons of Liberty) dared to remain loyal to the king and were willing to help enforce British laws in America.

While most often associated with Massachusetts and Boston, the practice was not localized just there. In fact, the first tarring and feathering before the Revolution occurred in Virginia in 1766. This was the tarring and feathering of William Smith in Norfolk, Virginia who was punished for notifying royal officials of contraband aboard a ship. Afterwards he was dropped in the harbor where he nearly drowned. From 1766 to 1776, there were more than 70 recorded incidents of tarring and feathering occurring all across the American colonies from New Hampshire to Georgia.

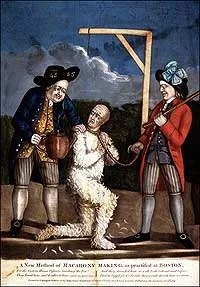

Perhaps the most egregious and violent tarring and feathering was that of John Malcom, a 51-year-old customs official in Boston. On January 25, 1774, Malcom struck a patriot supporter George Hewes in the streets of Boston. That night a crowd of patriots gathered outside of his home. They dragged him from his house, stripped him of his clothes, and poured hot tar over his body which scalded his skin. They then broke open pillows and covered him in feathers. They placed him on a cart and paraded him through the town of Boston. They passed the Old State House, the Old South Meeting House and the Liberty Tree. Along the way he was severely whipped and beaten with sticks and other objects. The crowd demanded he curse the royal governor and the king, which he refused. After being subjected to further beatings and whippings and threats of more bodily harm (including the threat of cutting off his ears), he ultimately gave in and cursed them. The crowd then forced him to drink tea until he vomited. He then was beaten more until he was finally dropped back at his home after the five hour ordeal. He survived the punishment but would carry the scars of that night for the rest of his life. When removing the tar from his body, the doctors noted that “flesh comes off his back in stakes.” The notorious event was immortalized in a cartoon by Philip Dawe in England entitled “The Bostonians Paying the Excise-Man, or, Tarring & Feathering”.

These violent means of punishing Loyalists and tax collectors was meant to intimidate opponents of their cause but increasingly came to be viewed as appalling forms of anarchy and mob tyranny. Many Bostonians recoiled in anger and fear at the brutality of John Malcom’s punishment, and the Sons of Liberty attempted to curtail such punishments in the future. After this, the patriots of Boston stopped tarring and feathering people even as other areas in Massachusetts and other colonies continued to do so over the next few years.

While the use of tar and feathers was popular amongst patriots in the lead up to the war, there is at least one instance of British soldiers using it on a patriot. In March of 1775, patriot Thomas Ditson was caught attempting to buy a musket from a British soldier in the 47th Regiment of Foot in Boston. Ditson was ordered by a British officer to be tarred and feathered for his offense. After taking his shirt off and tarring and feathering him, he was paraded through Boston along with British fifers and drummers who mockingly played “Yankee Doodle.”

There were dozens of tarring and feathering incidents in 1775 and 1776, but after 1776, there are very few recorded instances of it happening. One of the last recorded incidents also happened to be the only time it immediately preceded an execution. In Charleston, South Carolina in December of 1776, a “dissenting minister” named John Roberts was tarred and feathered by a large mob. Afterwards, the mob erected a gibbet and Roberts was hanged. They then torched the gibbet which, along with Roberts, were “consumed to ashes.”

As the war progressed, such protests and demonstrations died down. The use of tar and feathers had been used effectively by patriots as a powerful symbol both locally and abroad as to who held power in colonial communities. However, the wielding of such intimidating tactics made many American colonists and leaders uncomfortable. Many of the founders feared that such actions would lead to mob rule or “mobocracy.” These fears were given further justification when they witnessed the violence that grew out of the French Revolution shortly after the Revolutionary War.

Similar tactics of tarring and feathering were used by the British in Ireland in the Irish Rebellion of 1798 on suspected rebels in a brutal tactic known as “pitch-capping.” Here, hot tar would be placed on the top of a person’s head and then a cap was placed on top this. After the tar cooled, the cap would be ripped off, tearing off portions of the person’s scalp. The effect left the person with permanent scarring and a similar warning to those who would defy British rule.

After the Revolutionary War, the use of tarring and feathering as a form of mob justice continued to occur sporadically up through the 19th and 20th centuries in America. Among the more famous instances was the tarring and feathering of Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints leader, Joseph Smith in 1832. African Americans, suffragists, and anti-war supporters were among those tarred and feathered over the centuries. Despite its continuous use, the cruel action is still mostly associated with the patriot fervor of the 1760s and 1770s colonial America. Effective as it was in the colonial era, to this day, the term tarring and feathering is still used as a shorthand of the frightening specter of the power of mob rule in American politics.