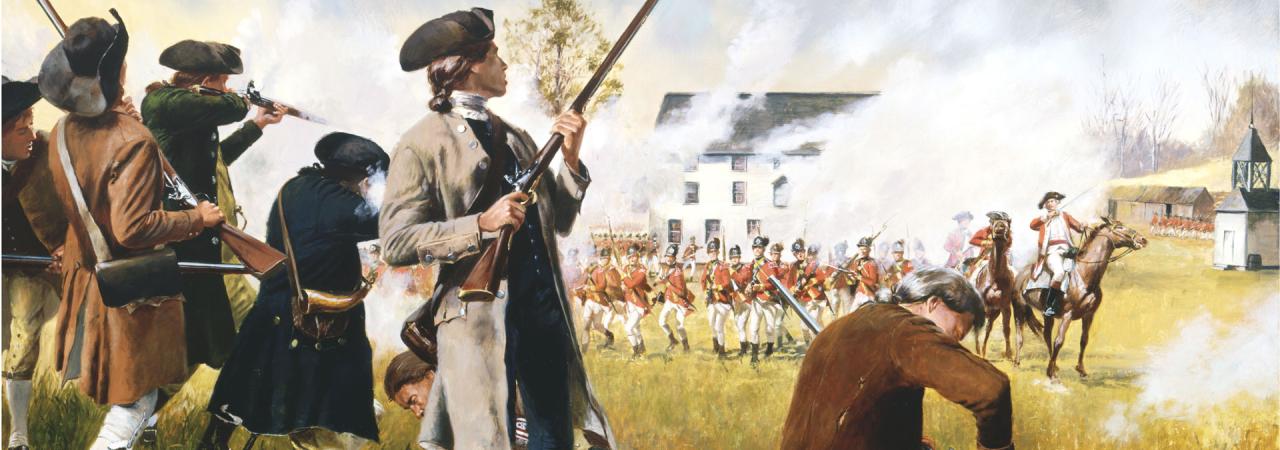

“Stand Your Guard,” a National Guard Heritage Painting by Don Troiani depicting the Battle of Lexington and Concord.

Fact #1: Minutemen vs. Militia

The most prevalent stories around Lexington and Concord is that of the “Minutemen.” If one visits Lexington and Concord today they will not only come across monuments to the Minutemen but also the National Park that commemorates the actions of April 19, 1775, is called Minute Man National Historical Park. Minuteman companies were officially created by the Massachusetts Provincial Congress in October 1774 to be the best soldiers of each militia company. They regularly trained, and some were paid. They were to respond, “at a minute’s notice.” Other colonies also adopted similar units naming them “training bands” or “minutemen.” On April 19, 1775 thousands of militia units responded to the alarm in Lexington and Concord from across New England. Despite the modern-day perception, the vast majority of the men who responded were not minutemen, but regular militia. Lexington, where today a monument to the Minutemen sits on the Battle Green, never created a Minuteman company. It was militia that met the British Regulars on the early morning of April 19, 1775.

Fact #2: Lexington was not the first place colonial militia and British Regulars faced off.

The events of April 19, 1775 were a culmination of many altercations between local militia and British Regular soldiers. On December 14 and 15, 1774, militia from Portsmouth, New Hampshire attacked Fort William and Mary. The British fort was undermanned (less than ten soldiers) but would not surrender to the militia force of nearly 300 men. Fighting ensued and one British soldier was wounded, the garrison surrendered and over the two days gunpowder, firearms and 16 cannon were captured. Though shots were exchanged from colonial militia and British Regulars, it did not lead to war. The events have mostly been forgotten today.

Fact #3: More than Paul Revere, dozens of colonial riders rode out on April 18-19, 1775

Paul Revere’s role in the events of April 18-19, 1775 is well documented in modern American literature. Revere, along with William Dawes, rode from Boston to Lexington to warn of the British Regulars march west. Many falsely believed the soldiers were on a mission to capture John Hancock and Samuel Adams. As Revere and Dawes rode towards Lexington, they handed off their message to other riders in the towns they rode through. Soon, dozens of riders were spreading the word as far away as New Hampshire and Connecticut by the end of the day. The network of information sharing was astounding and showed that colonial leaders were well organized. Though Revere is by far the most well-known rider that night, he was by far not the only one out that night spreading the word.

Fact #4: British General Thomas Gage’s goal was the military supplies in Concord, not John Hancock or Samuel Adams in Lexington.

The Sons of Liberty in Boston believed when British General Thomas Gage ordered the Regulars out towards Lexington that their mission was the capture of Samuel Adams and John Hancock. Adams and Hancock were seen as the leaders of Massachusetts colonial resistance. Adams, the passionate orator, and Hancock the financier worked together for a common goal. Many believed the King wanted both men captured and ordered Gage to capture them. Both men were in staying in Lexington on April 19, 1775, at the Hancock-Clarke House (Hancock himself had lived here briefly as a child). Gage’s mission for his Regulars was not the capture of the two Patriot leaders, but the weapons, supplies and cannons being stored in Concord by the Massachusetts Provincial Congress. The fact the road to Concord from Boston that Regulars took went through Lexington had nothing to do with the presence of Adams or Hancock.

Fact #5: The Lexington militia did not intend to fight the British Regulars.

The Lexington militiamen that filed onto the Lexington Green the morning of April 19, 1775, were there as a show of force, to remind British authorities that the colonists were armed and ready to defend themselves. Much like other militia units had shadowed other British Regular excursions (most notably at Salem, Massachusetts on February 26, 1775), the Lexington militia had no intention in getting into a firefight with the Regulars. Captain John Parker proved to be a steady leader of the militia that morning, he knew it would be suicide for his 80 men to take on the 400 well-trained British Regulars. The position of Parker’s men to the side of the road to Concord show that Parker had no intention of blocking their route to Concord. Post war accounts of Parkers words that morning have been exaggerated, but his actions and primary accounts of those who were there prove that Parker had no intention of getting into a battle that morning.

Fact #6: No one knows who fired the first shot at Lexington

One of the biggest mysteries of April 19, 1775, is who fired the first shot at Lexington. Both sides claimed the other side shot first, thus placing blame on their enemy for the bloodshed that ensued. It seems everyone interviewed after the events of April 19th had a varied answer to this question. It is obvious confusion and chaos infringed on everyone’s view of the events. There is evidence that points to either a quick trigger by one of the men on the Lexington green or a spectator firing from behind a stone wall near Buckman’s Tavern. We will never know who fired the first shot, but it was a spark that lit a world war.

Fact #7: The bloodiest stretch of “Battle Road” was in Menotomy.

Nearly 130 colonial militiamen and Regulars were killed on April 19, 1775. The fighting along the “Battle Road” grew bloody as the Regulars marched from Concord towards Lexington and back to Boston. But the bloodiest and fiercest fighting took place in Menotomy (modern-day Arlington) along modern-day Massachusetts Avenue. Here the fighting became hand to hand and brutal. Harassed for miles, British soldiers began to go house to house clearing families from the buildings along the road. In the fighting in this stretch, nearly 25 colonists and 40 British regulars were killed, half the day’s death count.

Fact #8: Despite modern-day pop culture references, there is no evidence to suggest that General Gage’s wife, Margaret Kemble Gage, was a spy for the Sons of Liberty.

One of the mysteries surrounding the events in Boston in the spring of 1775 is how Joseph Warren and the Sons of Liberty were able to gather such top secret information on the British military in Boston. Warren, John Hancock, Sam Adams, Paul Revere, and others perfected the process of gathering information and spreading that information across their network in New England. The plans that General Thomas Gage devised for April 19, 1775, were only shared with a few people in his inner circle, though there are indications that Warren and his colleagues knew about the plans before many in the British ranks. One of the much-suggested sources for this information was Gage’s wife, Margaret Kemble Gage. She was born in New Jersey to a wealthy family, Margaret married Gage in 1758. Many of her writings show her divided loyalties, typical of many of the time. The evidence to attach her as a colonial spy is very circumstantial and has never been proven. Soon after the fighting in April, she went to England and many have pointed to this as Gage’s disapproval of his wife’s supposed role in Warren’s spy ring. In some popular culture references, Margaret Gage is shown as a romantic interest of Joseph Warren. Despite being a good story, there is no evidence that Mrs. Gage was the source of information for the Patriots in Boston.

Fact #9: The Birthplace of the United States armed forces is considered by many to be at David Brown’s Farm near the North Bridge.

Though officially June 14, 1775, is considered the birthdate of the United States Army (the date the Continental Congress authorized the enlistment of riflemen to serve for one year), the Brown Farm is considered by some historians as the true birthplace of the United States armed forces. It was on the farm of David Brown, just west of the North Bridge that mixed companies of militia and minutemen gathered under arms and orders to confront British Regulars at the North Bridge. For the first time in combat formation, these men moved towards battle at the North Bridge. Today, a US flag flies from the location now known as the “muster field.”

Fact #10: The fighting on April 19, 1775, is one of the best documented battles of the American Revolution

After the fighting ended at Lexington and Concord, the Massachusetts Provincial Congress began to take dispositions from those involved in the fighting on April 19, 1775. Colonial leaders were experts in public relations and knew that they needed to control the narrative of the events in Lexington and Concord if they were to succeed in a revolution. They believed that General Gage and the British military were the aggressors and agitators and knew it would be important to portray them as such as they attempted to gain other colonial support within North America. Dozens of these interviews were conducted in the days, weeks, and months after the fighting. Hundreds of pages of transcripts from these interviews are still available today. Likewise, albeit a little later, British authorities took dispositions from their soldiers as well. As the war progressed, both sides spent a lot less time getting testimonies from those involved in battles. These accounts after Lexington and Concord from both sides gives historians a great insight into the events of April 19, 1775, in an otherwise under documented period of history.

Related Battles

93

300