Terribly Torn at Every Step

Note: In September 2011, the Civil War Trust, its members, and local preservationists helped save a 5-acre section of the Franklin battlefield. This section of the battlefield was utilized by Edward Walthall's Confederate troops as they assaulted the Eastern flank of the Union line at Franklin.

The Battle of Franklin, fought on November 30, 1864, has been considered by many to be one of the bloodiest battles of the American Civil War. In the course of 5 short hours, the Confederate Army of Tennessee thrust itself against a strongly entrenched Federal force under the command of John Schofield. Despite their great offensive élan and superior numbers, the Confederate forces outside of the Union main works at Franklin suffered enormous casualties.

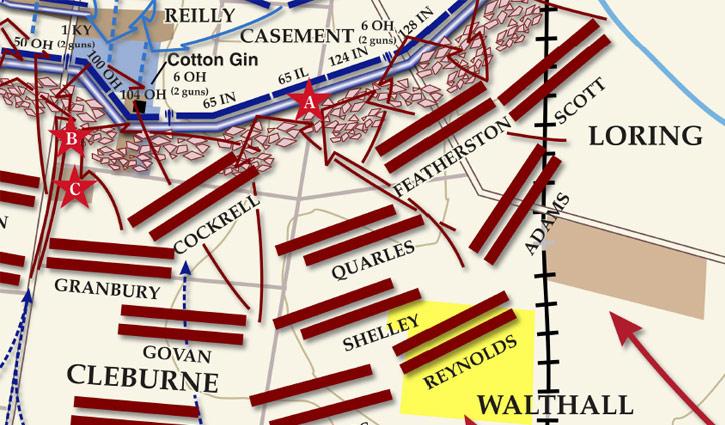

This article will attempt to describe many of the interlocking defensive advantages that the Union forces possessed at Franklin. To be more specific, this article will focus on the section of the Union main line that ran between the Cotton Gin and the Lewisburg Pike – an oft-overlooked section of the line that Maj. Gen. Edward Walthall’s Division of Tennesseans, Alabamians, Mississippians, and Arkansas struck. Defending this section of the line where the men of Col. John Stephen Casement’s Second Brigade of Brig. Gen. Jacob Cox’s Third Division. These Federal infantrymen were bolstered by the presence of several batteries of light artillery from the 1st and 6th Ohio Light Artillery.

Long Range Devastation – 3-inch Rifled Guns

One of the first defenses that Walthall’s men confronted were the artillery pieces located in Fort Granger. The 3-inch rifled guns of Capt. Giles Cockerill’s Battery D, 1st Ohio Light Artillery were positioned within this earthen fort atop Figuers Hill. From this strategic position across the Harpeth River, Cockerill’s men were ideally situated to attack, en enfilade, the Confederate infantrymen approaching the left side of the Union main line at Franklin. The position of Fort Granger gave it one more chief advantage in that the purported protection offered by the Nashville & Decatur Railroad embankment that passed through this section of the battlefield was completely exposed to fire from the guns of Fort Granger.

Once Walthall’s men emerged from the relative protection of the McGavock Woods, Union gunners unleashed a devastating fire upon the advancing Confederates. These seasoned artillerymen, quickly cutting their timed fuses, were able to accurately time the explosion of their artillery shells so that the shrapnel would explode just above their rebel foe. The deadly fire from these exploding 3-inch artillery shells, as reported by Indiana soldiers in the main line, mowed the Confederates down, “ making great holes in their ranks.”

A Hail of Projectiles - Close-Range Artillery

As the resolute men of Walthall’s brigades advanced closer to the Union main line they would have next encountered the powerful blasts of 12-pounder Napoleon smoothbore cannon situated in embrasures near the Cotton Gin and the Lewisburg Pike. The flat, open terrain in front of the Federal line provided Walthall’s men little cover from the screaming rounds being fired by Lt. Aaron Baldwin’s 6th Ohio Light Battery.

At under 400 yards, most of the Union guns switched over to deadly canister shells – real short range killers. Canister shells for 12-pdr Napoleon guns contained 27 balls (each about 1 1/12” in diameter) that would spray out from the muzzle at more than 1,200 feet per second. Like a large shotgun, these smoothbores could do devastating work against closely packed attackers.

During the frantic assault on the Union left flank, Baldwin’s guns reportedly fired “triple canister” – three canister shells stacked on top of one another. There were even accounts of Lt. Baldwin asking men to load musket balls into socks that would then be loaded into the hot cannon tubes.

Doing the terrible math, each veteran gun crew, firing triple canister, firing three times a minute, would therefore have unleashed 243 deadly canister balls every minute. At Franklin, this veritable blizzard of iron balls extracted a terrible toll from Walthall’s exposed men.

Firepower - Henry Rifles

The advent of the rifled musket had greatly extended the accuracy and killing range of the average Civil War infantryman. While most of Colonel John Casement’s 2nd Brigade shouldered standard issue rifled Springfield muskets, reports show that both the 65th Illinois and 65th Indiana were partially equipped with a new and deadly infantry weapon – the 16-shot Henry repeating rifle.

The Henry Rifle, first produced in number in late 1862, was the progenitor of the famous Winchester rifle of Old West fame. These lever-action repeating rifles carried fifteen .44 caliber cartridges in a magazine located under the barrel. A veteran infantryman firing a standard Springfield or Enfield rifle could fire 2 or 3 rounds a minute. With a Henry in hand, a trained rifleman could fire 28 rounds in a minute. Many a quartermaster flinched at the potential headaches in keeping Henry-equipped troops supplied with their special rimfire cartridges, but at close range this huge increase in firepower provided Casement’s men with a tremendous advantage.

Edward Walthall, a veteran of many of the hardest fought battles in the Western theater, stated in his official after-action report that his troops faced by “far the most deadly fire of both small-arms and artillery that I have ever seen troops subjected to.”

Obstacles - Osage Orange Abatis

As the remnants of Walthall’s command approached the Union main line they would have encountered a nasty, thorn-filled line of Osage Orange branches – the Osage Orange Abatis. The Federal defenders along this section of the line had placed these intertwined branches from their far left near the Harpeth River to within maybe 300ft of the Cotton Gin. The abatis’ job was to slow the advance of the Confederate attackers. Once slowed, the rebel infantrymen would be easier targets for Union riflemen and cannoneers manning the line. Many accounts tell of Confederate infantrymen attempting to use the butts of their rifles to smash their way through this tangle. Other frantic soldiers simply resorted to trying to climb over the thorny branches.

One other chief defensive advantage of the abatis was that it broke down unit cohesion since it was nearly impossible for large bodies of troops to pass through this obstacle together.

In Eric Jacobson’s For Cause and For Country, he states that “the ‘mangled and torn remains’ [of Confederate soldiers] created a macabre spectacle as they hung partially suspended in the thorny branches. Countless others, trapped or restricted in their movements, became easy targets for the Federal soldiers.”

Entrenchments – The Union Main Line

Exposed to the awesome destructive powers of the Civil War battlefield, it had become almost standard operating procedure for large bodies of soldiers to build entrenchments, time permitting. At Spotsylvania Courthouse, Petersburg, Atlanta, and countless other battlefields, by 1864 soldiers had become convinced of the true defensive advantages of fighting from behind some sort of well-constructed earthen wall.

With a more numerous Confederate army in hot pursuit, the tired Union soldiers needed little convincing of the need to stack their arms and to pick up an entrenching tool. Each regiment, positioned along their designated section of the line, quickly organized into work details. Pickaxes, shovels, saws, and hammers were all used to quickly create a formidable earthen line. Nearby structures, like the Cotton Gin, were partially stripped of their thick wooden boards, and nearby railroad ties and fence rails were put to good use as “head logs” – heavy wooden beams designed to protect an infantryman’s head as he fired above the parapet. By the time that John Bell Hood was ready to unleash his assault, the Federal forces were well set behind these walls of Tennessee dirt.

This Union main line, anchored on the Harpeth River, both left and right, left its soldiers in a very strong position. It is a testament to the strength of these works that John Casement’s brigade only reported 3 killed and 16 wounded during the Battle of Franklin. When compared to the more than 580 casualties that Edward Walthall’s forces suffered in the attack on November 30, 1864, it is easy to see the tremendous advantage that these entrenchments afforded their defenders.

The Ascendancy of Defense

In examining each of these Union defensive advantages it's essential to realize that all of these systems were designed to work together. Long range rifled artillery would disrupt enemy formations at a distance. Rifled guns and canister firing artillery would devastate those that made it closer to the line, and obstacles and entrenchments would eliminate any remaining momentum that the attacker possessed. It was here at the Battle of Franklin that the great offensive determination of the Confederate Army of Tennessee met the grim realities of fighting veteran defenders, wielding the latest in armaments, fighting from behind well-built entrenchments. The lopsided results in favor of the Federal forces on November 30, 1864 is just one clear example of how the nature of combat had shifted heavily in favor of the well-prepared defender – a trend that many military historians feel remained unaltered until the advent of modern tanks and close-support attack aircraft, almost 75 years later.

Sources

For Cause and for Country: A Study of the Affair at Spring Hill and the Battle of Franklin by Eric Jacobson, published 2008

Official Records, Numbers 246. Reports of Major General Edward C. Walthall, C. S. Army, commanding division and rear guard of infantry, of operations November 20, 1864-January 8, 1865.

Special thanks to Tracey McIntire for her research on Civil War artillery matters.