“They Came with Barbarian Yells and Smoking Pistols”

By J. David Petruzzi and Steven Stanley

At 7:00 a.m. on the morning of June 19, 1863, Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee ordered Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell to march his corps into Pennsylvania ahead of the rest of the Army of Northern Virginia. Ewell was to advance his men toward the Susquehanna River, and if Harrisburg (the state capital) “comes within your means, capture it.”

On June 24, Ewell sent his right column, the 6,500 men of Maj. Gen. Jubal A. Early’s Division, to Greenwood (today called Black Gap). Lt. Col. Elijah V. White’s 35th Battalion Virginia Cavalry, about 250 troopers, and the 17th Virginia Cavalry under Col. William French, another 250 men, escorted Early. The following day Early received orders from Ewell (who was at Chambersburg) to march to Gettysburg and then on to York, where he was to cut the Northern Central Railroad and burn the Wrightsville bridge across the Susquehanna. Early was to then join Ewell at Carlisle for a planned assault upon Harrisburg.

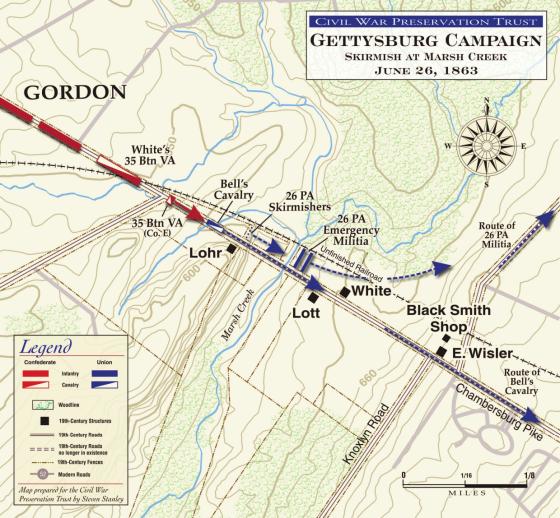

At 8:00 a.m. on the morning of Friday, June 26, a cold rain fell as Early’s men marched toward Gettysburg. Two miles from their camp, they burned Thaddeus Stevens’ Caledonia Furnace Iron Works. A few miles west of Cashtown, Early received information that local militia were at Gettysburg. He decided the best way to approach the potential threat was to divide his force and arrive from two angles — just in case he met a stubborn resistance. Early sent the 1,900 men of Gordon’s Brigade and White’s troopers on the straight path to Gettysburg, the Cashtown Pike, while Early led the balance of his division and French’s cavalry on a road to the north known as the Hilltown Road. Gordon had orders to engage any enemy troops on his front, while the rest of Early’s men approached Gettysburg from what was thought to be the rear of the right flank of the militia.

In answer to Lee’s threatened invasion of the North, several Pennsylvania militia troops were mobilized in late June to protect the Cashtown Pass area and the Cumberland Valley. On June 18, the 26th Pennsylvania Emergency Militia mustered into duty with 743 officers and men. The commander of the Department of the Susquehanna, Maj. Gen. Darius N. Couch, dispatched the green regiment to Gettysburg, where it arrived by train at about 9:00 a.m. on June 26. The regiment was commanded by 24-year-old Col. William W. Jennings, and was made up mostly of soldiers from the central part of the state, including one company of 56 students from Pennsylvania (now Gettysburg) College. Capt. Samuel J. Randall’s First Troop, Philadelphia City Cavalry, was already in town, having arrived five days earlier.

A local cavalry unit, Capt. Robert Bell’s Adams County Cavalry Company, was comprised of approximately 50 locals mounted on their own horses and without uniforms. Bell, a 33-year-old farmer, had formed the company on June 16. Bell’s troopers joined the militia, and all were under the command of Maj. Granville O. Haller of the 7th U. S. Infantry, whom Couch had designated to organize the defense of the area.

Unaware of Early’s approach, at 10:30 a.m. Haller ordered Jennings to march west on the Chambersburg Pike and take up a position to delay any Southern advance into Adams County. Jennings balked at the order, citing the inexperience of his troops, but Haller insisted. After detailing one company of the 26th Pennsylvania and Randall’s cavalry to remain in town and protect the regimental baggage, Jennings marched off through a fog and drizzling rain, with Bell’s cavalry leading the way.

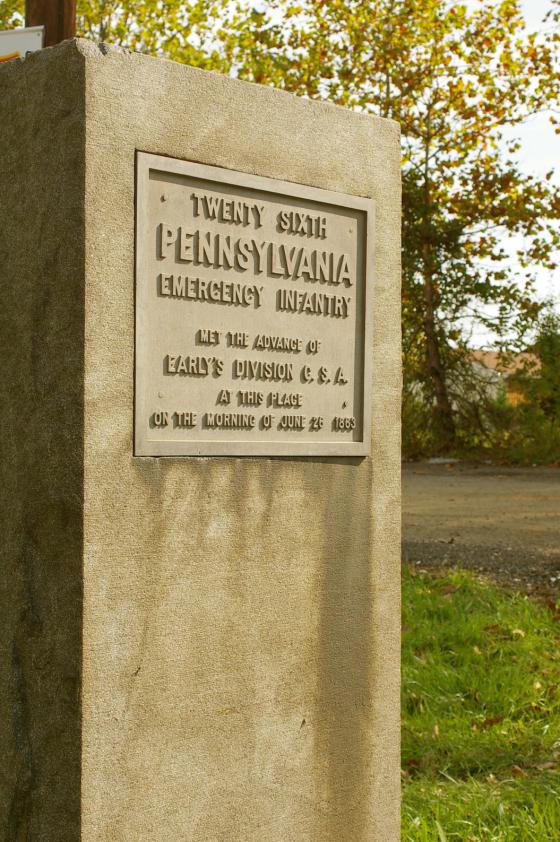

The column halted at a bridge over Marsh Creek, and Jennings detailed forty of his “best” men from the 26th Pennsylvania and some of Bell’s troopers across the creek to form a picket line. Other cavaliers advanced 200 yards west to watch the road, while the rest of the militia set up camp on the north side of the road in a clover field east of the creek. Unaware that Early was marching straight at them, many pitched tents to shelter themselves from the rain.

Jennings and Bell rode a few hundred yards to get a better westward view atop a rise today called Knoxlyn or Wisler Ridge. Reports that Rebels were in force to their front began arriving, and they soon spotted White’s cavalry descending a slight slope in the road about two miles away. One of Bell’s cavalrymen rode into the camp yelling that the enemy was “quite near.” Jennings had no illusion of holding back the Confederate troopers, especially if they were leading a large column of Southern infantry. He and Bell rode back to the camp and ordered the soldiers to strike tents, roll their packs, and retreat east in the direction of Gettysburg.

The militiamen quickly gathered their gear and began marching northeast through farm fields. Bell’s cavalry and Jenning’s pickets, however, held their ground and were soon spotted by White’s battalion of Virginia Cavalry. Led by Methodist preacher turned- warrior Lt. Harrison M. Strickler and his Co. E, White’s troopers raised an ear-piercing Rebel Yell and charged down the road. “They came with barbarian yells and smoking pistols, in such a desperate dash,” Capt. Frank Myers, the regimental historian of White’s cavalry, wrote of his comrades’ charge, “that the blue-coated troopers wheeled their horses and departed ... without firing a shot.... Of course, ‘nobody was hurt,’ if we except one fat militia Captain, who, in his exertion to be first to surrender, managed to get himself run over by one of Company E’s horses, and was bruised somewhat.” White’s cavalrymen captured nearly three dozen prisoners. While a few pursued Bell’s galloped retreat, most of White’s troopers raided the hastily abandoned infantry camp in the field.

Jenning’s militiamen ran through the fields east of Marsh Creek until they reached today’s Belmont Road, which they followed to the Mummasburg Road. From there, Jennings intended to reach the Gettysburg railroad station and then follow the tracks to Harrisburg.

The uncaptured remnants of Bell’s cavalry galloped east on the pike toward Gettysburg. After galloping through town, Bell gathered the remainder of his men near Rock Creek on the Hanover Road and, declaring, “Every man for himself,” ordered them to their homes. Bell and some of his men, along with Maj. Haller and Randall’s cavalry, rode on to Hanover, then to York and Wrightsville.

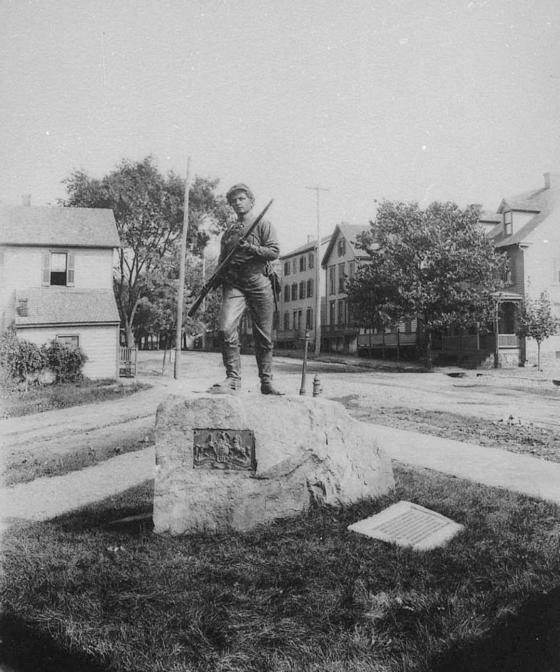

After being dismissed by Bell, Pvts. George Washington Sandoe and William Lightner rode the low land along Rock Creek west of town to reach the Baltimore Pike at about 4:00 p.m. Unseen behind the scrub trees that lined the road, a few of White’s Confederate cavalry made their way down the pike and, upon seeing the mounted troopers, ordered them to surrender. Sandoe quickly pulled his revolver and fired at the Southerners. Lightner’s horse was able to jump a fence and carry him to safety, but his companion’s steed balked at the fence. Sandoe was shot in the head and left breast by one of White’s men, fell from his horse, and lay dead in the road. Sandoe is often referred to as the first Federal casualty at Gettysburg, although the battle proper would not start for another few days.

The Confederates took Sandoe’s horse and rode back toward town, leaving the young cavalryman where he lay. Later, one of White’s men told a local, “the ---- shot at me, but he did not hit me, and I shot at him and blowed him down like nothing, and here I got his horse and he lays down the pike.”

Early that evening, local miller James McAllister came upon Sandoe’s body, but didn’t recognize the young man. He placed the body in his wagon, and a neighbor identified the corpse. After learning he lived south of Mt. Joy Church (in an area called Barlow today) a few miles south of Gettysburg, McAllister took Sandoe there, where his wife awaited his return from assignment in Gettysburg. George and Diana Sandoe had only been married a few months.

Back in the town square, White’s cavalry looted and ransacked many of the homes while terrified citizens tried to hide their horses and valuables. Gordon’s foot soldiers, escorting the captured militiamen, entered along Chambersburg Street and filed into the square.

French’s 17th Virginia Cavalry tailed Jennings’ militia about three and a half miles northeast of Gettysburg to the farm of Henry Witmer, where the militia had stopped briefly to rest and get food and water. The Confederates formed on Bayly’s Hill to attack the Pennsylvanians formed along the road.

Some of Bell’s cavalry were with the militia as well, and Jennings had approximately 600 men total. Near the bottom of the valley, at a wooden bridge that crossed a small stream, Jennings placed a rear guard of about 80 men of Company B under Capt. Warner H. Carnahan. French’s cavalrymen formed a battle line, sounded their bugles, and slowly advanced at the militia skirmish line and camp beyond. Seeing the Confederate advance, Jennings broke his men’s respite and deployed them along a fence behind the skirmish line.

Jennings ordered his men to fire a volley, which unhorsed some of the Southern cavalry. French’s horsemen fired a volley of their own, which wounded and killed several of the militia. Jennings again decided that further resistance was futile and ordered his men to retreat east through the fields. Jennings tried to form another battle line beyond the hill southeast of Witmer’s farmhouse but was relieved that French did not pursue; the Confederates were happy enough to round up Capt. Carnahan’s rear guard and another 100 of the militia as prisoners, about 175 men in all. French stripped his captives of their new guns and shoes, and held them prisoner at the Witmer farm. On the afternoon of June 28, Jennings arrived at Harrisburg with his fellow escapees to report to Governor Andrew Curtin that he had lost Gettysburg to the Confederates — an episode that paled in comparison to the fighting about to befall the town.

Toward evening, General Jubal Early rode through the square to the courthouse, where the militia captured at Marsh Creek had been gathered to hear a stern tongue-lashing from the Virginian. “You boys ought to be home with your mothers and not out in the fields where it is dangerous and you might get hurt!” he rebuked them. They were then locked in the courthouse.

In the first block of Baltimore Street, Early wrote out a list of demands from the town, including sixty barrels of flour, 6,000 pounds of bacon, 1,000 pairs of shoes and 500 hats. Borough Council President David Kendlehart, after consulting the council, instead invited Early to search the shops for supplies, but little was found.

Early gathered his men and left east on the York Pike. Several of Gordon’s men chopped down the flagpole in the center of the square, and the railroad bridge spanning Rock Creek was torched as the Confederates left town. Most of Early’s men camped near Mummasburg, northeast of Gettysburg, before proceeding toward York at daybreak. They would return a few days later to take part in a battle foreshadowed by the skirmishes of June 26.

Learn More: The Complete Guide to Gettysburg is available from our Civil War Trust-Amazon Bookstore

J. David Petruzzi has written widely on the Civil War and the Battle of Gettysburg in particular. In addition to numerous articles, he is a co-author of bestsellers Plenty of Blame to Go Around: Jeb Stuart’s Controversial Ride to Gettysburg and One Continuous Fight: The Retreat From Gettysburg and the Pursuit of Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, both published by Savas Beatie. An insurance broker, Petruzzi lives in Brockway, Pennsylvania with his wife Karen and daughter Ashley.

Steven Stanley is a full-time graphic artist specializing in historical map design and battlefield photography. His maps, considered among the best in historical cartography, have appeared in a variety of publications and are a staple of CWPT preservation and interpretation projects. Stanley lives in Gettysburg.