By Mark A. Snell

In 1895, when Theodore Lang, a former major in the 6th West Virginia Cavalry, published his version of West Virginia’s contribution to the Union war effort, he began with a description of the differences between the eastern part of Virginia and the TransMontaigne section of the Commonwealth. According to Lang:

The men of the west [at the time of settlement] were hardy frontiersmen, a majority of them soldiers of the Revolution and their immediate descendants, with little but the honorable record of patriotic service and their own strong arms for their fortunes. They had few slaves ... they depended upon their own labor for a new home in the wilderness.

Although his portrayal of the region that would become West Virginia was simplistic, almost stereotypical, his conclusion concerning the dissimilarities of the two regions and the political hostilities they engendered was fairly accurate: “A population thus originating, a community thus founded was naturally uncongenial to the aristocratic element of the Old Dominion.” Just to be sure his readers understood the dividing line between the sections, he specified that “the Blue Ridge was the boundary between eastern and western Virginia.”

If the Blue Ridge Mountains are used as the geographical boundary, however, his conclusions bear scrutiny: the residents of Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley were, for the most part, staunch supporters of the Confederacy, as were many of the citizens of the three counties that comprise West Virginia’s “eastern panhandle.” Scores of residents of the Kanawha River Valley of West Virginia also swore their allegiance to the Commonwealth of Virginia and the Confederate States of America, as did much of the population of the southwest portion of West Virginia. Perhaps Lang’s most telling assertion was that the people from the area that would become West Virginia “had few slaves.”

Most Civil War scholars agree that the immediate cause of the Civil War was the election of Abraham Lincoln, a Republican whose party platform included a plank calling for the non-extension of slavery. In 1860, the year of the presidential election that elevated Lincoln to the highest office in the land, there were nearly 491,000 slaves in the Commonwealth of Virginia, yet only 18,371 resided in Western Virginia. Those slaves in the latter group were held by 3,593 owners, out of a white population of 376,677 — one slaveholder per 100 white citizens. Most Western Virginia slaves lived along the Potomac River and in the far southeastern counties or the Valley of the Great Kanawha, those areas of the future state that, for the most part, voted for the Old Dominion to leave the Union in the Secession Ordinance Referendum of May 23, 1861.

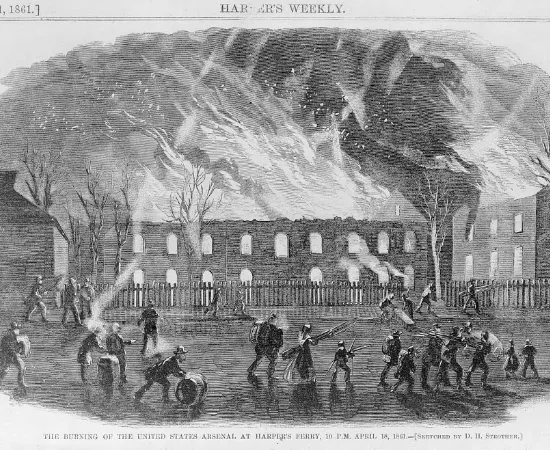

According to the 1860 U.S. Census, 3,960 slaves were held in bondage in Jefferson County, the easternmost county in what would become West Virginia. There, at the confluence of the Shenandoah and Potomac Rivers, sat the important little manufacturing town of Harpers Ferry, which had become the center of a maelstrom in October 1859, when militant abolitionist John Brown and a group of supporters raided the U.S. Armory located there. Their goal was to capture national attention by stealing enough weapons from the arsenal to arm the slaves of Jefferson and other counties in the region and then take to the nearby mountains to evade federal authority and establish a provisional U.S. government. These plans came to an inglorious and rapid end as Brown was captured and tried by the Commonwealth of Virginia for murder, treason and inciting a slave insurrection — all capital charges. Following a speedy trial, he was convicted on all counts and was hanged on December 2, 1859.

Brown’s raid sent fears of slave insurrection throughout the South as the pivotal presidential election of 1860 approached. The Democratic Party could not decide on a single suitable candidate, which allowed factions of the party to nominate a Northern candidate, Stephen Douglas of Illinois, and a Southerner, Vice President John C. Breckinridge. Also on the ballot were the Constitutional Union Party’s John Bell and Republican Abraham Lincoln. In the area that would become West Virginia, voters were nearly evenly split between Breckinridge (21,908) and Bell (20,977), although Virginia as a whole was carried by the latter. Lincoln’s miniscule support (1,921 votes) was centered in the northern panhandle counties, where he still lost to both Breckinridge and Bell.

The status of slavery was not a direct political issue in much of the future state of West Virginia. In fact, most opposition was because the institution was seen as a hindrance to free labor, not for moral reasons. During the decades prior to the war, issues revolving around taxation, internal improvements and political apportionment were more significant in pitting western Virginians — particularly those from the northwest region of the state — against their eastern counterparts. It was in this northwest region that the strongest support for the Union could be found, a region with very few slaves and inhabitants who shared far more cultural, social, ideological and economic similarities with their neighbors in southwestern Pennsylvania and eastern and southeastern Ohio than with the rest of the Commonwealth of Virginia. “Whatever … [these] forces had individually,” wrote historian Richard Orr Curry, “collectively they tipped the balance in Northwestern Virginia in favor of Unionism in 1861.”

In December 1860, political leaders in South Carolina pulled their state out of the Union and, in the next two months, other states of the Deep South followed her lead. Western Virginia politicians, however, had met at Clarksburg on November 24, 1860, to preemptively condemn secession and resist a Virginia secession convention. Nevertheless, on January 21, 1861, the Commonwealth’s General Assembly adopted a proclamation stating that in the event of hostilities between North and South, Virginia would side with the slaveholding states that already had seceded. In Parkersburg, in Wood County on the Ohio River, the prevailing mood was much different. There, at a meeting held three weeks before the General Assembly’s proclamation in support for the slaveholding states, a resolution was passed that stated, “Resolved: that the doctrine of Secession of a State has no warrant in the Constitution, and that such doctrine would be fatal to the Union, and all the purposes of its creation; and in the judgment of this meeting, secession is revolution.”

After the provisional army of the Confederate States of America opened fire on Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861, President Lincoln called on the loyal states — including the slaveholding states that still remained in the Union — for 75,000 volunteers to quell the “rebellion.” When Virginia governor John Letcher received the telegram requesting troops, he quickly shot back his refusal: “The militia of Virginia will not be furnished to the powers at Washington for any such use or purpose as they have in view.” The Virginia Secession Convention passed its own Ordinance of Secession on April 17, 1861, by a vote of 88–55, with 48 dissenting votes cast by delegates from the lower (northern) Shenandoah Valley and the TransMontaigne. Twenty-five northwestern Virginia delegates voted against secession; only five were in favor and two abstained.

In the aftermath of that vote, the Virginia militia seized the U.S. Arsenal and Armory at Harpers Ferry and the U.S. Navy Yard at Norfolk — an illegal act because the convention had required that the Ordinance of Secession be put to a popular referendum, scheduled to occur on May 23, 1861. As Harpers Ferry was about to fall into secessionist hands, the officer responsible for the security of the federal installation had incinerated the arsenal and all of its stored weapons. Virginia militiamen, however, had doused the flames in the armory buildings, saving the important rifle-manufacturing equipment, which promptly was disassembled and shipped south to armories in Richmond and Fayetteville, North Carolina.

Some 250 miles to the west, Unionist delegates from 24 northwestern Virginia counties and three Shenandoah Valley counties met in Wheeling, western Virginia’s largest city, from May 13–15 to confer and deliberate the secession crisis. But one delegate, John S. Carlile, had different motives. A native of Harrison County, Carlile was a former U.S. representative and among those delegates who had voted against Virginia’s secession at the Richmond convention. Returning home, he penned the “Clarksburg Resolutions,” intending to determine the course of action that the people of the northwest counties would take next and urging the formation of a provisional “loyal” government. Other influential delegates, including Waitman T. Willey and Francis Pierpont, cautioned those in attendance at the so-called First Wheeling Convention not to be too rash, urging that no formal action be taken until the votes of the statewide Secession Referendum on May 23 were tabulated. Undaunted, Carlile pushed for the immediate creation of the state of “New Virginia.” According to Carlile, “After the 23rd of this month, it will not be a constitutional right [to separate from Virginia]. We will have been transferred to the Southern Confederacy.” Carlile was ruled out of order, and moderation won the day. If the Secession Ordinance passed the referendum, as was expected, only then would steps be taken to form a new state government. In anticipation of what seemed to be the inevitable, the delegates passed a resolution to meet on June 4 for a “Second Wheeling Convention.” Meanwhile, at the ballot box on May 23, the 48 counties of the future state of West Virginia were evenly divided, with half voting to secede from the Union, a portent of the divided loyalties that would manifest on the battlefield.

Not far from where Carlile wrote the Clarksburg Resolutions and less than a week before the Secession Referendum, Frederick W. Bartlett of Fairmont, Marion County, and a tailor by occupation, enlisted in Company A, 31st Virginia Infantry, on May 17, 1861. He had been quite excited about joining the military, as he told his Fairmont neighbor, Lt. William P. Cooper of the 31st, who was enquiring about a tailor-made uniform. According to Bartlett, “Send me a sample of the goods so that I can get me a uniform. I want to join your company so that I can give the Abolitionists the benefit of a Virginia cartridge in the neighborhood of the guts.”

Referring to the heated and sometimes physical altercations caused by the political crisis, Bartlett wrote: “I am just itching and sp[o]iling for a fight. I have not had one since last Monday, and of course I am getting very rusty. I dislike this fighting a la plug ugly. I want to try them with powder and lead.” Most likely, he had tussled with a Unionist who attended a political rally in Fairmont on Monday, May 6. The broadside advertising the public meeting announced, “AMERICANS, we ask you, come to the rescue of your country, and our country’s cause. Our chains are being forged; the clanking may be heard in Richmond, in that secret, that dark and damnable convention. Then let all come to the rescue. The great champion of Western Virginia, HON. JOHN S. CARLILE, will be there to address the people. Let us give him a warm and glorious reception.” Bartlett, perhaps fortified with liquid refreshment, thus gave one of Carlile’s supporters his own version of “a warm and glorious reception.” The soon-to-be soldier had been swept away by what the French called rage militaire — a passion for armed conflict that usually recedes after the first bloody battle.

In Philippi, Barbour County, the citizenry was also busy taking sides. Even Carlile’s old law firm was split over the secession crisis — attorney Samuel Woods was one of the county’s outspoken and respected advocates for secession, while his law partner, Spencer Dayton, was an outright loyalist of the Union. These former friends and business associates rallied their followers through speeches and newspaper appeals, with Dayton declaring the Confederates to be enemies of the “liberties of mankind,” while Woods felt that the Lincoln administration would strangle Virginians’ rights and liberties. At this stage in the conflict, however, the concerns of the white residents of Barbour County “centered on the rights and wrongs of secession,” writes a recent historian who studied the effects of the war on Barbour County, “and in that context support for the Union among slave owners was no more a contradiction than support for secession among those opposed to slavery.”

Four days after the Secession Referendum, on May 27, Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan crossed the Ohio River at Parkersburg with troops from Indiana and united with parts of two regiments of “loyal” Virginia Volunteers, securing northwest Virginia for the Union. His command soon was joined by an Ohio regiment that crossed the river at Wheeling. But even before McClellan’s troops had crossed the Ohio, blood had been shed in the region. On May 22, Union militiaman Thornsberry Bailey Brown was shot by a Confederate militiaman near Grafton, an important junction on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, becoming the first man killed in hostile action during the Civil War. Brown’s body was returned to Grafton, where it was placed on view for friends and curious onlookers as they voted on the Secession Referendum. Early the next day, Brown’s former unit, the “Grafton Guards,” hopped a train for Wheeling to be mustered into the Union army as Company B, 2nd Virginia [U.S.] Infantry.

About 10 miles up the Potomac River from Harpers Ferry, a privately owned covered bridge spanned the watercourse, linking Jefferson County, Virginia, to Washington County, Maryland. Sitting astride the toll bridge on the Maryland side was a plantation known as “Ferry Hill Place,” owned by the Rev. Robert Douglas, a shareholder in the bridge. In mid-June 1861, Maj. Gen. Joseph E. Johnston, commander of Confederate troops at Harpers Ferry, ordered Col. Thomas J. Jackson, who had been raised near Clarksburg before attending West Point, to send a detachment to

Shepherdstown to burn the bridge as Confederate forces prepared to evacuate Harpers Ferry. One of the young soldiers tasked with this mission was Pvt. Henry Kyd Douglas of the 2nd Virginia Infantry, with its Company B composed of men from Shepherdstown and environs. Douglas was born in Shepherdstown and was the son of Reverend Douglas. In his memoir, Henry wrote: “When, in the glare of the burning timbers, I saw the glowing windows in my home on the hill beyond the river, and knew my father was a stockholder in the property I was helping to destroy, I realized that war had begun.”

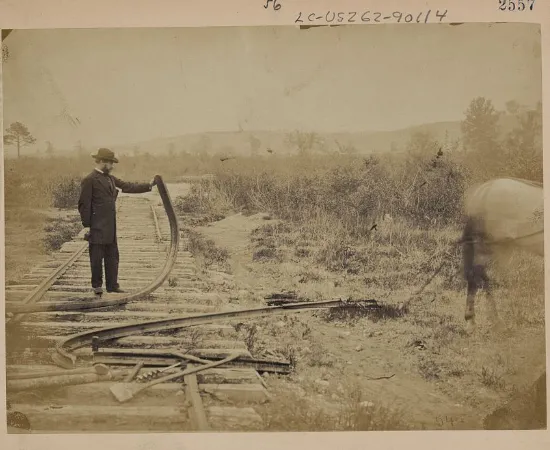

Moving on to Martinsburg, on June 20 troops from Jackson’s command — which, ironically, also included a detachment of young men from Wheeling, Company G (“the Shriver Grays”) of the 27th Virginia Infantry — torched the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad’s roundhouses and rolling stock, tore up some tracks and then managed to drag 10 locomotive engines over the Valley Turnpike to Winchester. All told, Jackson’s men destroyed 42 engines and 300 freight cars, the single largest capture and destruction of railway equipment during the entire Civil War.

Now that Virginia had officially seceded from the United States, delegates to the Second Wheeling Convention took action. On June 13, 1861, with Union forces in control of northwestern Virginia, representatives to the convention voted in favor of the reorganization of the government of the Commonwealth of Virginia. Dennis B. Dorsey of Monongalia County urged the immediate creation of a new state, but John Carlile, who had agitated for separation from Virginia during the First Wheeling Convention, now cautioned the delegates not to be too hasty. Carlile told his listeners:

Let us assemble a Legislature here, on our own, to support the constitution of our fathers. Let us organize a Legislature, swearing allegiance to that government, and let the Legislature be recognized by the United States Government, as the Legislature of Virginia and then we will effect this separation. It is a mere question now, of whether we shall wait until we are solemnly recognized as the true, legal, constitutional representatives of the people of Virginia; or whether we shall now attempt an impossibility.

On June 19, the convention passed an ordinance to create a loyal state government, with a governor, lieutenant governor, attorney general and advisory council. The Second Wheeling Convention finally adjourned on June 25, with its members agreeing to meet again in the same city on August 6, 1861. Attorney Francis Pierpont of Marion County was elected by the delegates to be the new governor of the “Restored Government of Virginia” and thus would appoint the commanders of the state’s regiments.

The die had been cast for the eventual formation of what would become the 35th state, but first the Union’s military forces — including those from Restored Virginia — would have to ensure the continued safety of the new government. During the summer of 1861, at places called Philippi, Rich Mountain, Laurel Hill, Corrick’s Ford and Cheat Mountain, those Union forces would do just that.