Colonel Emerson Opdycke is up early on May 8, 1864. He has been marching for most of the last week—the first halting steps of Union General William T. Sherman’s spring campaign in Georgia. At 4:00am he scribbles a note to his wife, Lucy. “The scenery here is very fine, mountainous of course, ridge upon ridge in quick succession, and the foliage is well out.” Their son, Leonard, has just turned six.

News of the fighting in Virginia is filtering through the ranks and Opdycke hopes that he and his men can “put a period to the war in this section, then aid Grant.” The brigade bugler blows officer call, Opdycke closes his letter, and is off to meet with his commanding officer.

Opdycke gallops off to meet with his brigade commander, General Charles G. Harker, a curly-haired West Pointer, just 26 years old. Showing Opdycke a map, Harker explains the situation. The Rebels hold nearly impregnable earthworks on the ridges surrounding Dalton, Georgia, a key stop on the railroad to Atlanta.

Their orders are to effect a lodgment on one of those ridges: an almost 600-foot eminence call Rocky Face Ridge. If the Federals can get troops on top of Rocky Face, they may be able to force the Confederates out of their positions around Dalton.

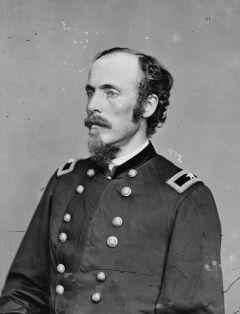

It’s a nearly impossible task, but Harker’s brigade has developed a reputation for doing the impossible. Opdycke in particular—a 34 year old part owner of a saddle shop—has distinguished himself through battlefield exploits, not military schooling. Harker orders his regiment, the 125th Ohio—“Opdycke’s Tigers”—will lead the advance with the rest of the brigade in support.

Due to the strength of Confederate works east of Rocky Face, Opdycke sees “but one practicable place of ascent”—the steep, boulder-strewn western slope. As if the climb itself wasn’t going be hard enough, the crest of the ridge is “so narrow as to render it impossible for more than four men to march abreast upon it.” Even after Opdycke gets his men up the slope, he will have no way of bringing his regiment into anything resembling a battle line should he encounter Confederates atop the ridge.

And that’s exactly what happens. The Tigers scale Rocky Face, the men pulling themselves up by grasping saplings and vines along the way. They sweep away Confederate pickets and gain the crest. But Opdycke’s men have barely caught their breath when “an advancing force” of Confederates comes up from the southern end of, leaping among the boulders. Somehow, Opdycke strings a company front across the narrow spine, checks the Rebels’ advance, and drives them back to “a strong stone work” which Opdycke calls “musket-proof.” He scribbles a note to Harker: “The crest is ours and we are driving the enemy South toward Dalton.”

Harker does not want to exceed orders. The crest is his objective. He tells Opdycke to hold tight while additional troops clamber up the slope. By the next morning, Harker’s entire brigade is in position, with two pieces of artillery in support, and signalmen wig-wag information about the Confederate positions down to the generals in the valley. Around 5:30 on May 9, however, Harker receives another impossible order: advance his brigade south along Rocky Face Ridge and assault the stone fortress.

The results are predictable. The terrain forces Harker to send in one regiment at a time, each one advancing “by the flank”—four men abreast. This makes the Yankees easy targets for the Confederates lurking behind boulders. Opdycke watches as the regiments in front of him—the 79th Illinois, the 64th Ohio, then the 3rd Kentucky—are chewed up in these “fruitless” assaults.

He jots another letter to Lucy:

I am now writing while the regiment is awaiting the advance of the skirmish line; the balls whiz about us saucily, cutting off limbs, one of which just fell upon this paper, a ball a few moments ago struck above my head and dropped down upon my hat rim. Occasionally the heavy boom of artillery fills the valley below with reverberating sound.

Then it’s time to move forward. The ground is so uneven that men can scarcely stay in formation. They fall over, some men plummeting as far as ten feet. Lieutenant Colonel David Moore and about 30 Tigers rush ahead, nearly to the works, but the Rebels are serving up “severe musketry from behind complete protection.” One bullet passes through the head of a corporal before striking Moore in the hip—one of four wounds he receives this day. The men who aren’t struck down dive for cover and stay there until nightfall allows them to sneak away.

The battle lasts for days. Opdycke and Harker hold their position through “drenching” rain and repeated skirmishes. Finally, on May 12, their comrades break through Snake Creek Gap and force the Confederate army to retreat towards Atlanta. The fighting is almost constant. On May 14, Opdycke is shot in the arm and nearly killed, but he refuses to go to the rear. As he explains to Lucy, “I shall stay until the Tigers go back, or until Peace smiles upon our native land…. that regiment will never be without a commander as long as I can sit upon a horse.”

Related Battles

837

600