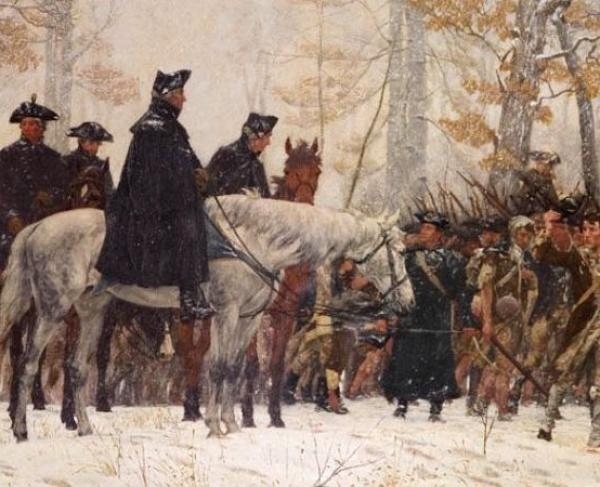

It’s a gripping story – the Continental army, on the brink of defeat, huddled together to survive the winter of 1777-1778 while Philadelphia, the American capital, lay in British hands. The encampment at Valley Forge is unsurprisingly an enduring tale in American mythos. It has inspired the subject matter of artists and authors, while scores of soldiers in America’s subsequent wars have related to the harsh winter and sacrifices made there. In the decades after the Revolution, Valley Forge grew to represent more than the role it played in American independence – it epitomized the American determination and grit required to surmount adversity of any kind.

However, the myth of Valley Forge proved more harrowing than the actual encampment. Though the Continentals endured a comparatively tolerable winter compared to the following one near Morristown, New Jersey, the army’s time at Valley Forge quickly became a much more famous and memorable story. In the decades after the war, the country grew to know Valley Forge as “the most critical hour in the long struggle” for independence, as the 1876 book Washington at Valley Forge remembered. Even those who partook in the campaign remembered that legendary winter as a time of great uncertainty and danger above others. Chief Justice John Marshall, a veteran of the Continental army, recalled that at no other period during the war “had the American Army been reduced to a situation of greater peril than during the winter at Valley Forge.”

After George Washington’s death in 1799, the nation quickly clambered his status, and that of the American Revolution, from history to legend. In his seminal biography of Washington, in which he included the infamous cherry tree myth, Mason Locke Weems chronicled the general’s experience at Valley Forge as divine. Weems recounted a story of questionable veracity in which a local Quaker, Isaac Potts, happens upon “the commander in chief of the American armies on his knees at prayer!” Weems wrote that the general, upon seeing Potts, rose from the snow “with the countenance of angelic serenity” and rode off to his headquarters. Then, the pious Quaker allegedly returned home to his wife and declared, “I always thought that the sword and the gospel were utterly inconsistent. But George Washington has this day convinced me of my mistake.”

Weems’s tale not only cemented George Washington as a figure of American mythic proportion but also promoted Valley Forge as an epitaph of hardship for the nation at large. While little evidence affirms the episode as historically accurate, artists, writers, and storytellers found muse in the parable of Washington’s prayer at Valley Forge by retelling it with brush and pen.

By the 1860s, the Valley Forge narrative took on new prominence to inspire a new generation of Americans at war. Citizens and soldiers on both sides of the Mason-Dixon line harkened to the sacrifices of American men and women alike. Sullivan Ballou invoked the spirit of his revolutionary forebears in his famous letter on July 14, 1861. “I know how strongly American civilization now leans upon the triumph of government,” he wrote, “and how great a debt we owe to those who went before us through the blood and suffering of the Revolution.” One Southern reporter encouraged Confederate women to emulate Martha Washington in her husband’s camp, where she “set an example to her lady visitors by diligently plying her needle, knitting stockings for the poor, destitute soldiers.”

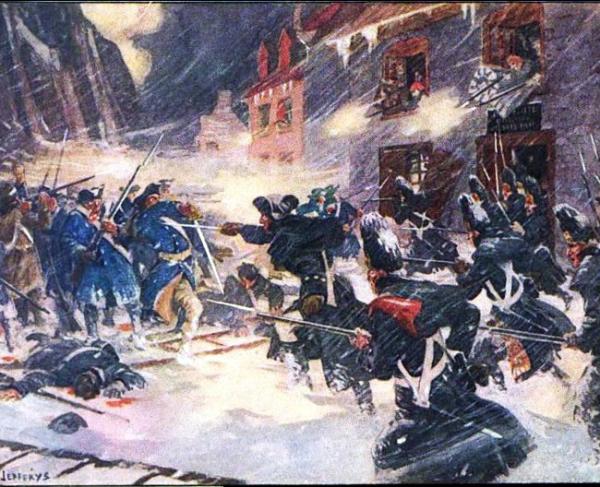

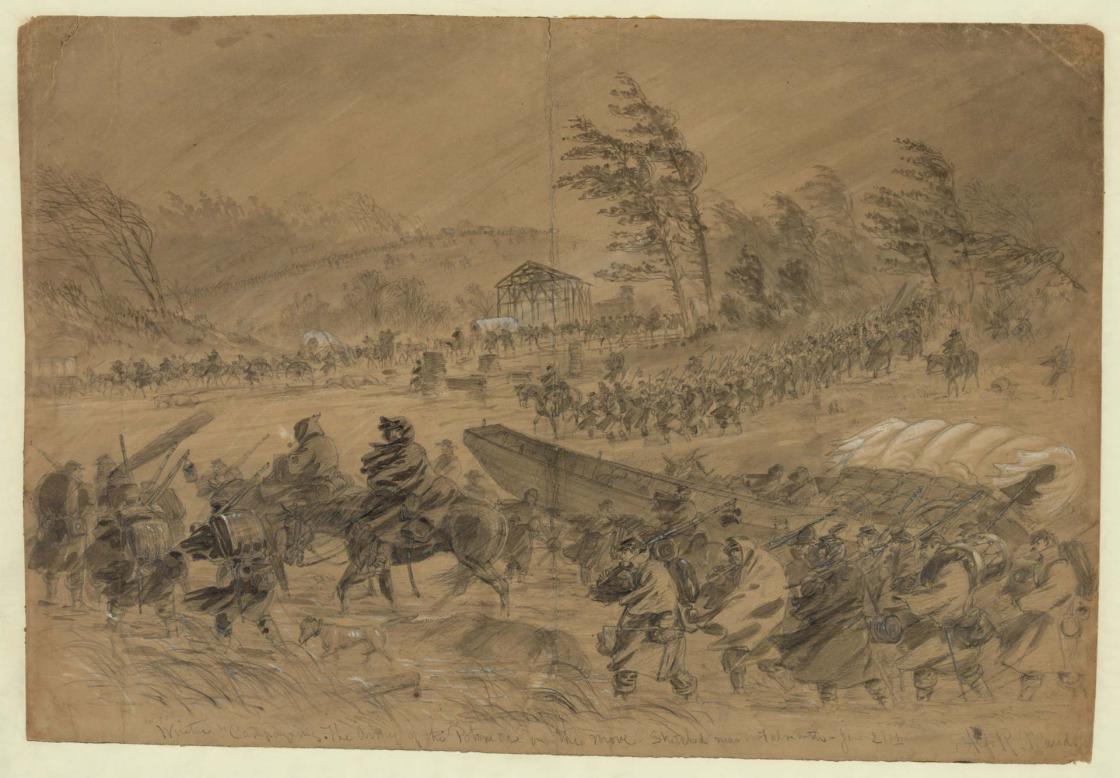

During the freezing winter of 1862-1863, dubbed the “Union’s Valley Forge”, numerous soldiers compared their agonizing experiences to that of their ancestors in the Revolution. Major Rufus Dawes of the 6th Wisconsin, great-grandson of Paul Revere’s compatriot William Dawes, wrote in December of 1862 that the harsh Virginia winter would be one of the most trying for the Army of the Potomac. “This winter is, indeed, the Valley Forge of the war,” Dawes mused. Gardner Stockton of the 5th Connecticut wrote that the Union camp near Falmouth, Virginia that year brought to mind “the wood-cut illustrations of the ‘Winter at Valley Forge’” from his school days and “the admiration then felt for the hero [Washington] and his never-to-be-forgotten campaign.” A soldier of the 107th New York similarly related that the men of their regiment often referred to their winter camp as “the Valley Forge of the 107th.”

Following the Civil War, the nation looked to Valley Forge as a tale reminiscent of their recent struggle for freedom and unity. Much like the country during the Civil War, the weary patriots endured pain, suffering, and death only to witness victory and a new future ahead of them. Contextualized by America’s legacy of enduring sacrifice and freedom, Valley Forge appeared in numerous works of art, literature, and song in the ensuing years. Thomas Buchanan Read wrote of that harrowing winter in his 1863 poetic collection Wagoner of the Alleghenies: A Poem of the Days of Seventy-Six, while W.W. Fink dramatically immortalized it in his long poem Valley Forge in 1870. Fink’s opening lines romantically set the scene of Valley Forge as a turning point in the nation’s storied past.

Seventeen hundred and seventy-seven!

Exposed to the withering winds of heaven,

Besieged by famine, and locked in the arms

Of snow-drifts, piled by the breadth of storms,

‘Twixt the desolate hills of Valley Forge,

On the Schuylkill’s bleak and frozen verge,

In the dreariest camp, an army lay

And longed for the winter to pass away.

Another poem, published by Harper’s Weekly in 1877, accompanied an illustrated scene of Washington's army in the snow and a veteran telling the story to his grandson. Such literature, common in the 19th Century, appealed to a sense of patriotism and pride in its readers. Americans demonstrated this pride in 1876 when spectators to Philadelphia’s Centennial Exhibition flocked to the fields of Valley Forge in commemoration of the 100-year anniversary of the American Revolution.

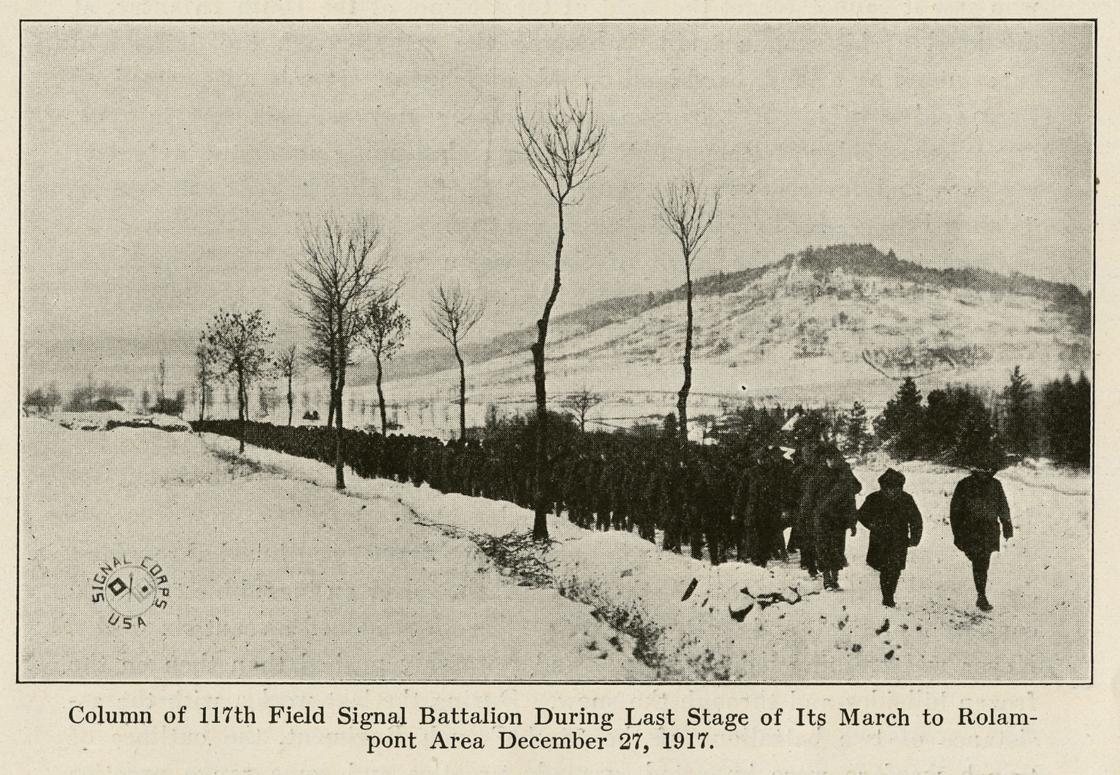

With the turn of the century and two World Wars, Americans again found new meaning from the winter of 1777-1778. In 1917, the Missouri National Guard soldiers of the 117th Field Signal Battalion embarked on a 100-kilometer march through the snowy French countryside which they dubbed the “Valley Forge Hike”. Later that year, a cartoon appeared in the New York Evening Post showing a bundled and shivering George Washington standing on snow-laden Capitol Hill. The caption, “Two Winters, Washington, 1917, Valley Forge, 1777,” invoked the spirit of the Continentals during Washington, D.C.’s frigid winter of 1917.

Another cartoon, from 1931 and the Great Depression, portrayed President Herbert Hoover dressed as George Washington comforting a cold, beleaguered elephant in the snow. Hoover exclaims, "Cheer up! Remember we won last time." That same year, President Hoover delivered a speech at Valley Forge, encouraging his audience to be "steadfast in our great traditions" as the country endured "another Valley Forge."

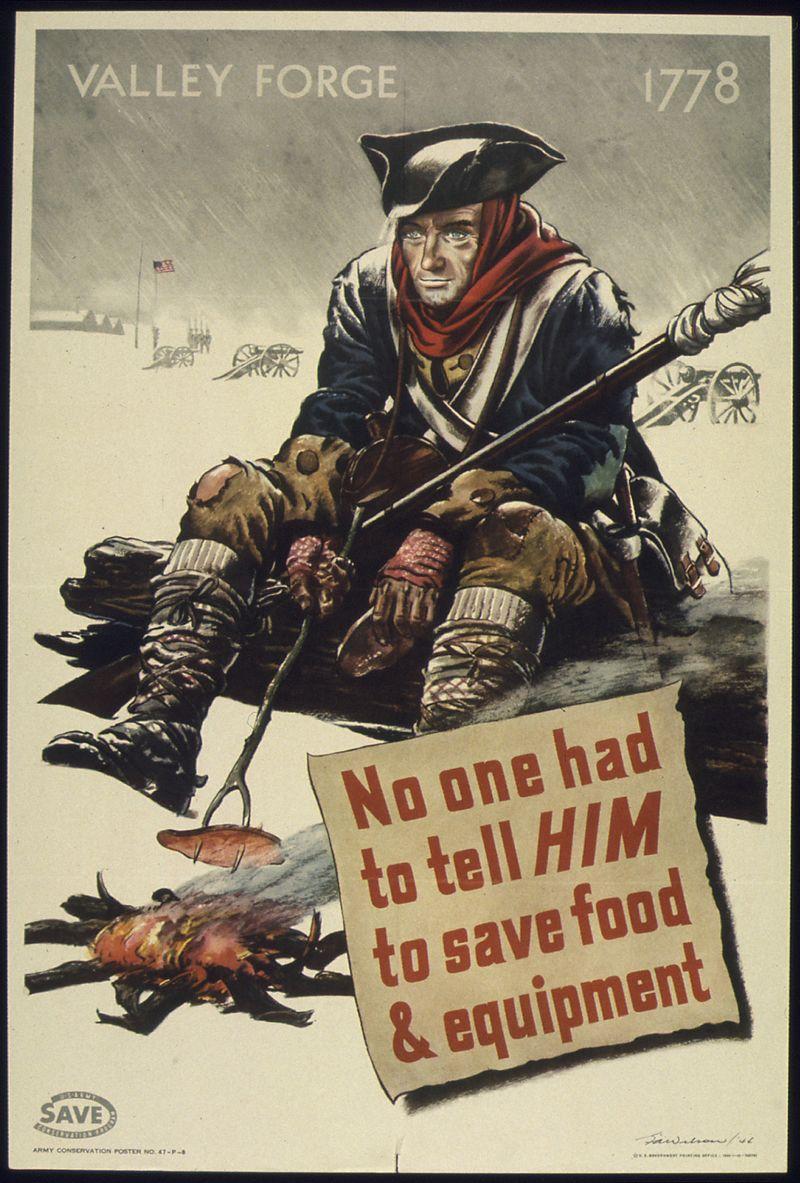

By the 1940s, American recruiters featured Valley Forge in propaganda posters, using the artistic images of soldiers huddled in the cold snow to inspire young Americans to slug it out in World War II. A series of caricatures, depicting Washington and his troops, consoled the nation as it experienced yet another national crisis. One cartoon illustrates Uncle Sam reading the “Bad News” of the Japanese bombing at Pearl Harbor to George Washington who reminds him that the country withstood greater challenges. As Americans responded with patriotic ardor to the Second World War, recruiting posters appealed to the courage of Washington’s soldiers as well as emphasized their frugality and sacrifice to citizens at home.

Decades later, Americans remembered Valley Forge with different meaning as Vietnam Veterans Against the War flocked to the fields in a 1970 protest. This shift in American memory also generated a reinterpretation of Valley Forge as an embodiment of suffering and death during war. Now citizens lined the fields of the site to bring an end to war when previously the story found meaning when encouraging Americans to persist in war.

Even nearly two centuries after that fateful winter, generations of Americans looked to that epic stay of Washington and his army as a tale which revealed something about themselves, regardless of its historicity. From Peanuts comic strips to classic American literature, Valley Forge remains a firm hallmark in American popular culture and memory. Perhaps John B.B. Trussell, Jr. best articulated the importance of Valley Forge in America’s identity in his 1974 work Epic on the Schuylkill: The Valley Forge Encampment. He argued that Valley Forge “has provided a symbol of patriotic devotion, epitomizing the ideal which brought our nation into being.”

Further Reading:

- "Revisiting the Prayer at Valley Forge" By: Blake McGready

- Valley Forge By: Bob Dury and Tom Clavin

- Epic on the Schuylkill: The Valley Forge Encampment By: John B.B. Trussell, Jr.

- Burying the Dead but Not the Past: Ladies' Memorial Associations and the Lost Cause By: Caroline E. Janney

- Seizing Destiny: The Army of the Potomac's "Valley Forge" and the Civil War Winter that Saved the Union By: Albert Z. Conner, Jr. and Christopher Mackowski