Overview

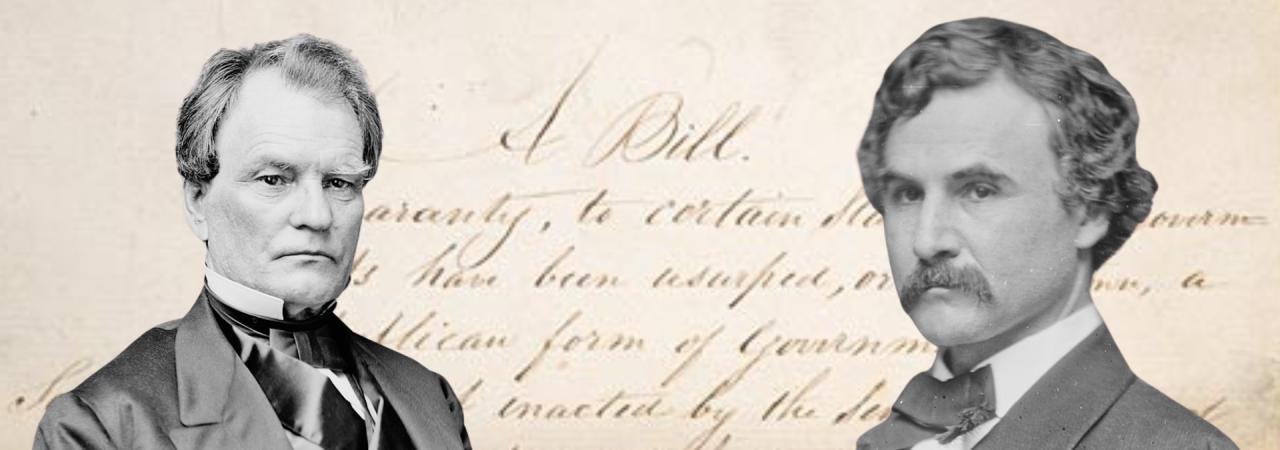

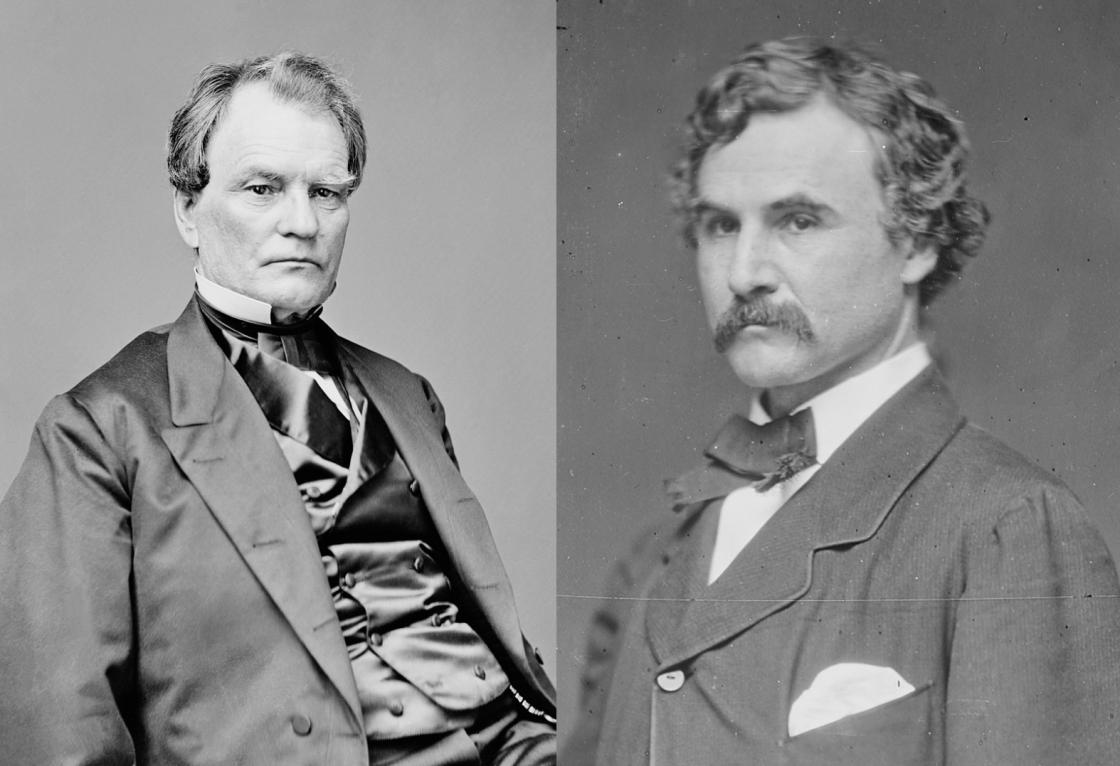

When President Abraham Lincoln presented his plans for Reconstruction to Congress, the “Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction,” also called the “Ten Percent Plan,” some political leaders, especially Radical Republicans, were taken aback by the leniency of the plan. While President Lincoln wanted to restore peace among the nation, the Radical Republicans believed that the Confederate States were traitors and should be punished as such. Therefore, Senator Benjamin Wade of Ohio and Representative Henry Winter Davis of Maryland drafted the Wade-Davis Bill, a new plan for Reconstruction that would hold the Confederates accountable for their disloyalty.

Background

In December 1863, during the war, the Union was achieving greater successes than the Confederacy, and some Confederate states were, at that point, willing to rebuild their governments in allegiance with the United States. President Abraham Lincoln had been making plans for the post-war Reconstruction period and determining the means by which to achieve peaceful coexistence between the states. He created a plan that focused on reintegrating the Confederate states into the Union as peacefully as possible. Lincoln wanted to take a moderate approach to the situation, allowing the rebel states to reintegrate following certain fulfilled conditions. His “Ten Percent Plan” required that 10% of the voters within the Confederate states swear allegiance to the Union and recognize the emancipation of former slaves. Lincoln also planned to pardon all members of the Confederate states, except the highest-ranking military and civil officers.

The Conditions of the Wade-Davis Bill

Dissatisfaction towards President Lincoln’s Reconstruction Plan echoed throughout Congress, especially among Radical Republicans. In response to Lincoln’s proposed plan, Senator Benjamin Wade joined forces with Representative Henry Winter Davis to craft the Wade-Davis Bill. Both Wade and Davis were outspoken Radical Republicans who sought retribution for the rebellion of the Confederate States. This Bill created stricter conditions by which the rebel states could rejoin the Union. The Wade-Davis Bill operated under the idea that Congress had the constitutional power to establish a republican government in the states. Within article 4, section 4 of the Constitution, Congress was in fact given this right; however, the Wade-Davis Bill used this right to determine that the responsibility of enacting post-war Reconstruction should be a power of Congress.

The Wade-Davis Bill required that 50% of all voters in the Confederate states, as opposed to Lincoln’s proposed 10%, must pledge allegiance to the Union before reunification. Along with the loyalty pledge, the Bill would abolish slavery within the rebel states. Any person who tried to deprive their slaves of liberty would be fined and imprisoned. Furthermore, as punishment, voting rights would be taken away from anyone who fought willingly for the Confederacy. Anyone who continued to hold office for the rebellion after the war would be stripped of their citizenship. Provisional governors would be appointed to each Confederate state to ensure that the conditions of the Bill were followed and that republican governments were created within the states. No former Confederate states would be permitted to rejoin the Union until they had followed each of the conditions set forth and created a new republican government with a constitution that included the abolition of slavery. Furthermore, the Bill declared that the new state government would only be established after recognition from the President with the assent of Congress.

If it passed into law, the Wade-Davis bill would essentially gave Congress complete power over Reconstruction and the readmission of Confederate states into the Union. Until each rebel state created their new government, they would be subject to the power of Congress.

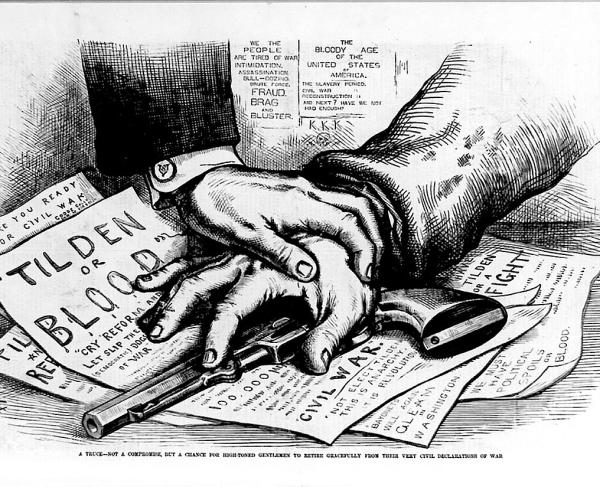

Response to the Wade-Davis Bill

On February 15, 1864, the Wade-Davis Bill was brought before the House of Representatives. In July of that year, the Wade-Davis Bill saw support as voting commenced. It passed through the House of Representatives with a vote of 73-59 in favor of the Bill. The Senate passed the Bill as well with a vote of 18-14 in favor. However, when the Bill was brought before President Lincoln to sign, he exercised a pocket-veto, meaning he refused to sign it before the adjournment of the congressional session. Without the signature of the President, the Wade-Davis Bill failed to become law. Lincoln’s veto infuriated Senator Benjamin Wade and Representative Henry Winter Davis, the authors of the Bill, who accused President Lincoln of trying to usurp power from Congress.

President Lincoln took issue with the Wade-Davis Bill for multiple reasons. He explained that at the time, he was unprepared to agree to a single plan for restoration. Primarily, Lincoln wished to see the country coexist as quickly and peacefully as possible after the end of the war. The Wade-Davis Bill stood as an obstacle to Lincoln’s goal, as it would slow the process of restoration and make it difficult for the Confederate states to begin participating in the Union once more. Furthermore, Lincoln did not believe that the Confederate states needed to “rejoin” the Union because constitutionally, they were not allowed to secede in the first place. Therefore, according to the President, the premise of the Wade-Davis Bill that called for the readmittance of the Confederate states was a null point. There was also an issue with the condition that each state must permanently abolish slavery. Because there was not, at that time, an amendment in the Constitution that abolished slavery, Congress had no right to enforce that federal requirement on each state. Lincoln decided instead that he would stand by his Emancipation Proclamation, and hope that his lenient plans for Reconstruction would encourage the rebel states to follow it.

At the time that the Wade-Davis Bill was presented, President Lincoln had also established pro-Union relationships with certain Confederate and Border states. Some of these states, including Louisiana, Arkansas, and Tennessee were already in the process of drafting new constitutions, and Lincoln did not want to nullify the progress that they had made. The passing of the Wade-Davis Bill would erase the efforts that these states had made, and Lincoln was unwilling to allow that to take place. Overall, President Lincoln and the Radical Republicans viewed the rebel states differently and had different opinions about how to reconstruct the United States after the war.

Further Reading: