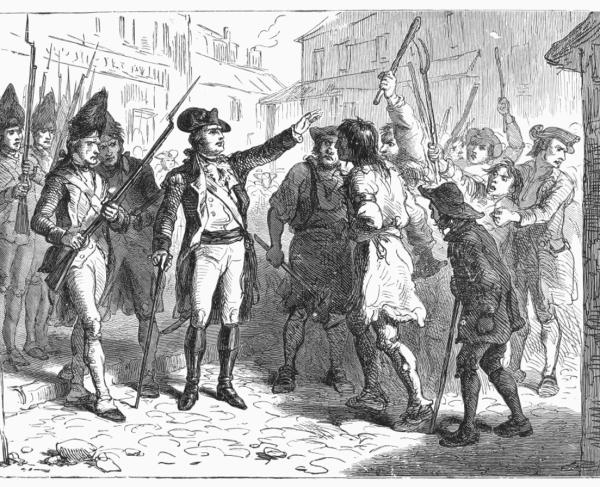

James Hunter, the so-called General of the Regulators. Alamance Battleground State Historic Site, Alamance County, N.C.

Four years before the American Revolution escalated into a war for independence, tensions gripped North Carolina that set a large portion of its citizens at war with each other. This crisis, known as the Regulator Movement or the War of the Regulation, began as a popular reform movement among small farmers, but ultimately turned deadly on May 16, 1771.

The roots of this movement can be found in the influx of immigrants who came to the North Carolina backcountry in search of cheap land. They found themselves straining against land speculators and public officials who the immigrants believed used their positions to enrich themselves at the expense of farmers. Dishonest public officials overcharged farmers on fees, and corrupt sheriffs over-collected taxes, pocketing the extra. These issues were exacerbated by other economically driven issues, such as shortages in available currency to settle debts and pay taxes. Enough farmers encountered the same issues that, in the mid-1760s, they started calling meetings and began to organize, naming themselves Regulators.

The Regulators tried various peaceful methods to obtain redress of their grievances. Community meetings led to associations and petitions, but petitions went unanswered. Regulators ran their own candidates for the Assembly and won several elections, but they were outnumbered, ignored and even censured by the legislators. They attempted to have their issues resolved in court, but “Courthouse Rings” run by the local elites made true justice unattainable. Finally, with frustrations mounting and no progress having been made, tempers boiled over and a crowd of Regulators rioted in the town of Hillsborough.

The Hillsborough Riot of 1770 found hundreds of Regulators targeting officials of the Superior Court when the court held its fall session in late September. The physical assaults and property damage were limited to those individuals the Regulators had taken issue with. For example, Regulators swarmed colonial official Edmund Fanning, dragging him by the feet out of the courthouse and beating him in the street. When he made his escape, the crowd moved on to his home. They broke inside; threw his money, valuables and furniture out of the windows; and then demolished the house.

Governor William Tryon seethed when he received the news of the riot. Having lost control of the backcountry, he began putting together the pieces to put down the Regulator movement by force. He first worked with the Assembly to pass a piece of legislation giving him sufficient power to raise an army and use deadly force against the Regulators. This legislation, colloquially known as the Johnston Riot Act (after its primary author Samuel Johnston), went to great lengths to stop the Regulators. It retroactively made all of the Hillsborough Riot participants outlaws, which allowed for the seizure of their property and gave Tryon authority to raise an army and use deadly force against those who had broken the law.

Samuel Cornell, North Carolina’s wealthiest citizen, personally bankrolled a large part of Tryon’s expedition and joined the governor as an adviser. He later wrote a letter to his friend, New York merchant Elias Desbrosses, describing the affair in great detail. Cornell’s money went toward enlistment bounties and daily pay for Tryon’s volunteers. By mid-May, his force stood at roughly 1,000 men and eight artillery pieces. At the Battle of Alamance, on May 16, they were opposed by approximately 2,000 Regulators. Tryon attempted to order the crowd to disperse, but his messengers received shouts of “Battle! Battle!” and “Fire and be damned!” Cornell remembered of the Regulators, “[N]ever did I see men so daring & desperate as they were,” recalling that before the battle began, many of the Regulators “would even run up to the mouths of our cannon & make use of the most aggrieving language that could be expressed, to induce the governor to fire on them; for they actually seemed impatient.”

Tryon eventually obliged and opened the battle with a volley from his artillery. The ensuing action lasted approximately two hours, as the unorganized Regulators sustained heavy casualties and gave way to Tryon’s volunteers.

In the aftermath, Tryon counted nine killed and 61 wounded from his own force and estimated 200–300 Regulator casualties. Local residents of the Moravian community at Bethabara wrote about seeing a man in town attempting to press their physician to help tend to wounded men after the battle. They later confirmed that the man was Regulator leader, Herman Husband.

In the years after the battle, many struggled to make sense of the movement and its bloody conclusion. Tryon’s successor, Governor Josiah Martin, proclaimed in an address to the North Carolina Assembly that all wished “that the veil of oblivion may be drawn over the past unhappy troubles” of the province. Boston lawyer — and Son of Liberty — Josiah Quincy inquired after the Regulators on his tour of North Carolina in 1773. He received conflicting versions of their story and intent and wrote in his diary that he was left to make up his own mind.

In the years after the American Revolution, memory of the battle shifted. The 1771 fight between two factions of North Carolinians turned into a battle between Regulators and British troops, as artistic depictions of the battle featured backwoodsmen facing off against unbroken lines of redcoat-clad troops. Local boosters began trumpeting the claim that Alamance was the “first battle of the revolution,” a superlative disproved by a close reading of primary sources from the Regulator movement. The reality is something much more complicated, and a forerunner to many of the popular movements and conflicts that later arose in the United States.