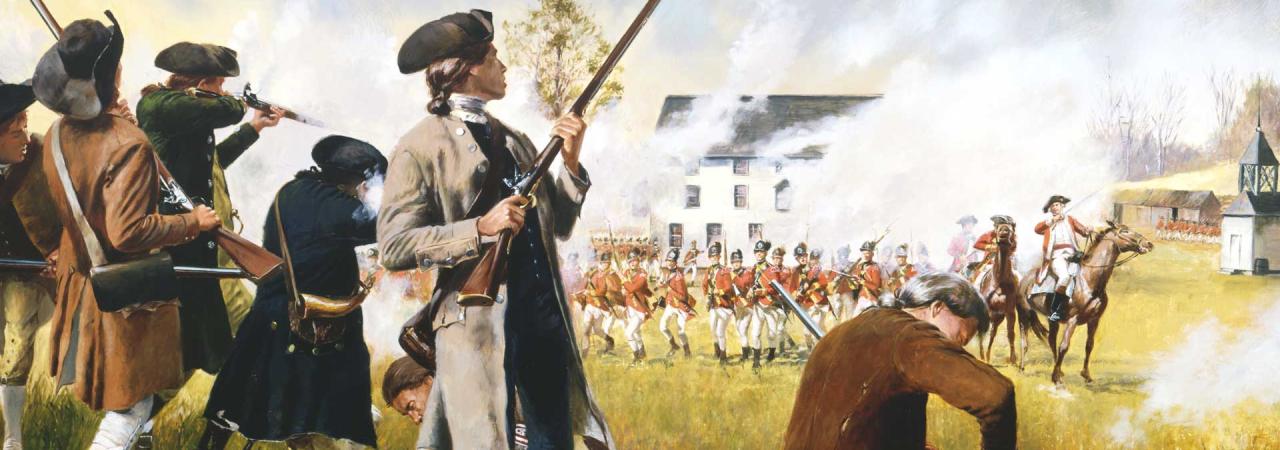

"Stand Your Ground," painting by Don Troiani.

The marker sits upon the northeast corner of the Town Common in Lexington, Massachusetts. The granite slab denotes the approximate spot where Lexington militia Captain John Parker formed the 77 men of his town’s company who had turned out in the early morning of April 19, 1775. They waited in anticipation for the arrival of roughly 700 British Regulars who marched towards the village from Boston, on the road toward Concord, during what was known in New England as “The Lexington Alarm.” What is remembered today as the first shots fired in the American Revolution would soon echo across the Common.

Emblazoned on the commemorative stone marker sitting on the Common today are these words:

Line of the Minutemen April 19, 1775

“Stand your ground. Don’t fire unless fired upon. But if they mean to have a war let it begin here.”

Captain Parker

Like many historical events, the fighting that occurred on Lexington Common in 1775 would be shrouded in its share of myths. Arguably the biggest myth that has been repeated over the years can be read on that commemorative granite marker: “Line of the Minutemen.” In truth, there were no minutemen on Lexington Common on that chilly April morning.

Since its founding in the early 17th Century, the Massachusetts Bay Colony had found itself almost continually embroiled in war, from conflicts with indigenous peoples to extensions of hostilities between England and France that had spread across the Atlantic from Europe. For many generations, every town in Massachusetts organized and maintained its own “training band”; military or militia units, comprised of local inhabitants who would turn out in times of emergency, often acting as an auxiliary to the regular military forces of Great Britain. When the danger had passed, the militia would return to their homes and private lives. Though there were exceptions, generally all able-bodied men between the ages of 16 and 60 were required to serve in the militia companies. These companies would muster at or near their towns at certain times of the year for drilling.

By the mid-17th Century, militia commanders began organizing smaller companies of men, taken from the ranks of the town militias, who could act as first responders in times of danger. Commanders were ordered, “to make a choice of thirty soldiers of their companies in ye hundred, who shall be ready at half an hour’s warning.” Later, on the verge of hostilities with the Wampanoag people led by King Phillip, militia regiments were ordered to “be ready to march on a moment’s warning, to prevent such danger as may seem to threaten us.” Eventually, these smaller units would come to be known as “minute companies.”

Generally, minute companies were comprised of young citizen-soldiers, 30 years of age or younger, who were quick, agile, and kept ready for deployment “in a minute’s notice.” Like most militia forces, they were armed and equipped at their own expense. By the 1750s during the French and Indian War, some companies began calling themselves “minutemen.” While all minutemen were part of the militia, not all militia troops were minutemen. Despite their designation, local troops were never held in high esteem by most regular officers of the British Army or political statesmen, who considered them at best, ill-trained amateurs and at worst, country bumpkins. In a letter written in 1754, by Lord William Anne Keppel, Earl of Albemarle, colonial troops “may have courage & resolution, but they have no Knowledge or Experience in our profession.” This would continue as an ongoing opinion among the British military until the time of the American Revolution.

In October 1774, in reply to the Massachusetts Government Act passed by the British Parliament, repealing the Massachusetts Charter of 1691, and giving exclusive power to the royally appointed governor, the Provincial Congress of Massachusetts was formed. This body would act as the government of Massachusetts outside of Boston. Among other things, it created a Committee of Safety and began collecting arms and ammunition as tensions with the mother country increased. The Provincial Congress, in an effort to reinvigorate the now aged militia system, recommended that all towns organize minute companies, to be ready to march “at the shortest notice.” After the Revolution, American General William Heath claimed that the first to answer this call in Massachusetts was his hometown of Roxbury. In December 1774, the town created a company of minutemen who were instructed to “hold themselves in readiness at a minute’s warning, complete in arms and ammunition; that is to say a good and sufficient firelock, bayonet, thirty rounds of powder and ball, pouch and knapsack.” The Roxbury minute company was required to drill twice per week and was paid for their service. Failure to appear at a scheduled muster could result in a stiff fine.

While each town’s process for establishing minute companies could certainly differ from others, most towns within the colony complied with the request of the Provincial Congress. Minute companies would, however, comprise only about a quarter of each town’s militia force. Overall, these elite, highly mobile companies were very well trained in the art of maneuver, usually the first to arrive at the scene of action, and in the use of their flintlock weapons, mainly smoothbore muskets, and fowling pieces. American long rifles, known for their extreme accuracy due to their elongated barrels with spiral grooves cut into the bore, were hardly seen in the northern colonies. Of basic German design, these weapons were mainly used by hunters in the Trans-Appalachian regions of western Virginia and Pennsylvania. Carried by hunters such as frontiersman Daniel Boone, by the late 1760s, these rifles would be taken into the new lands of Kentucky and would become commonly known, among other names, as Kentucky Long Rifles.

Although the Provincial Congress acted indeed as the de facto Massachusetts government, town leaders generally saw their requests as suggestions or guidelines rather than mandated orders. So, while many towns decided to follow the guidelines, establishing their own minute companies within their larger militia forces, others did not. One such town that never established a minute company from its ranks of militiamen, was Lexington. According to the town records, Lexington’s leaders made the decision to keep its militia in one large company body and continued to refer to it by the 17th-century term of “training band.” The commander, Captain John Parker, and other members of the company always referred to themselves as militia and not as minutemen.

On the morning of April 19, 1775, despite the myths and fireside stories that would be passed from one generation of Americans to the next, the truth is that there were no Lexington minutemen standing on the Village Green to witness the first shots of the American Revolution. Rather, standing on the Green with Captain Parker that fateful morning were men who made up, not a minute company, but a traditional New England training band. They were friends, neighbors, and kinsmen; they were the militia and brave men, all.

Related Battles

93

300