The Whirl of Death

Douglas Ullman, Jr. and Sam Smith

It is November 1863 and the pickets of Brig. Gen. Edward C. Walthall’s Mississippi brigade are standing within 40 yards of their Union counterparts, separated only by a small stream. When the officers move on, the private soldiers meet “half-way in the stream, where it was shallow and shoaly” and exchange newspapers, tobacco, canteens, coffee, and hats and shoes. They sometimes “talk for half an hour at a time,” according to 19-year old Southern private Robert Jarman.

Just north of the picket posts, the Union-occupied city of Chattanooga, Tennessee is being fortified day and night. Lookout Mountain towers to the east, behind the Confederate pickets, its summit wreathed in clouds. The Union pickets protect the tiny rail junction known as “Wauhatchie,” a vital link in the newly-established supply chain that saved the garrison of Chattanooga from starvation only weeks earlier.

The Confederate privates are anxious. Their siege is broken and Union reinforcements are gathering across the stream. To make matters worse, Lt. Gen. James Longstreet is leading his eastern front men off of Lookout Mountain, heading for Knoxville, more than 100 miles away. Nathan Bedford Forrest has accused commanding General Braxton Bragg of unmanly weakness. He is detaching his cavalrymen from the main army, threatening to kill any man who comes to him with Bragg’s orders. Perhaps the privates hear word of the months-long struggle for control of their army, the Army of Tennessee, which has led to this moment of division.

Walthall’s men are allotted three crackers and two spoons of sugar daily. Robert Jarman’s mess buddies have a comrade with the wagon train, though, and they benefit from a steady supply of bacon off the books.

The Mississippians know that they’re heavily outnumbered, that triumphant siege has devolved into desperate defense. Further up the mountain, along the plateau dominated by the boxy white house of Robert Cravens, John Moore and Edmund Pettus’s brigades of Alabamians and John Brown’s brigade of Tennesseans build a strong line of log and stone breastworks facing west and north. An attack is expected any day now.

Capt. Lewis R. Stegman is up early on the morning of November 22, 1863. He mounts his horse and rides toward Brown's Ferry. Lookout Mountain looms over his shoulder, a light mist enveloping it, adding an air of mystery to the already ominous scene. At a crossroads he sees a column of troops—western men from General Sherman's corps—making their way across the Tennessee River and into Chattanooga. The 23 year-old New Yorker surmises that his division will likely move next.

A group of horsemen galloping up the road toward him further arouses Stegman's suspicions. Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker, one-time commander of the Army of the Potomac, rides among them, joined by Stegman's division commander, Brig. Gen. John Geary. The coterie divides at the crossroads. Hooker and his staff continue on to Brown's Ferry; Geary makes his way toward the Twelfth Corps camps on Raccoon Mountain. Stegman feels as if "the very air had become stilled” as the generals rode by. When he returns from his ride he learns that his brigade is under orders to be ready to move at moment's notice. A major operation is near at hand and Stegman has the feeling that he and his men will be in the thick of it.

Stegman's regiment, the 102nd New York—men from Manhattan, Brooklyn, and Long Island—has fought in nearly every major battle in the east since Cedar Mountain, including the defense of Culp's Hill at Gettysburg. They spent most of October escorting the division's supply train through Tennessee and Alabama, missing the midnight fight at Wauhatchie. When they reached the Lookout Valley, the rest of their brigade—an all-New York outfit under Col. David Ireland—was digging trenches on Raccoon Mountain, settling in for winter quarters.

There is a running joke in Geary's division that one day old Joe Hooker will order them to take Lookout Mountain, but no one actually believes it. The steep, craggy slopes—forbidding in their own right—are crowned with artillery which occasionally sends missiles into the city below. Furthermore, Confederate signalmen atop Point Lookout are plainly visible. Every move the Federals make will be done in plain view of an enemy well-situated to repel an assault.

The warning order of November 22 is countermanded at midnight. The men of Ireland's brigade spend the following day listening to the sound of fighting some five miles away. Rumor that Sherman has taken a key position on the Union left filters through their camp.

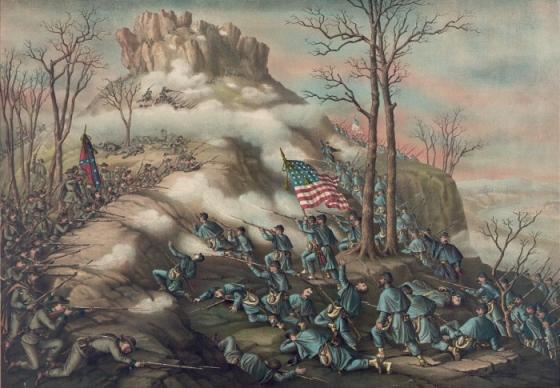

Reveille sounds before dawn on November 24. After a hasty breakfast each man receives 100 rounds of ammunition. Leaving their tents and blankets behind, they march across the battlefield of Wauhatchie before halting briefly at Lookout Creek. When the march resumes, the 60th New York leads Ireland's brigade up the slope. The hillside is steep, rocky, covered with underbrush: progress is slow-going. When the lead brigade can go no further, the men close their formation, face front, and lie down to rest while Geary explains the battle plan to his subordinates.

After a night of rain, a thick fog has set in, gathering low in the lightly wooded valley below Lookout Mountain. Robert Jarman of the 27th Mississippi is part of a two-mile-long Confederate skirmish line drawn across the western foot of the heights. The men of the main line stare down from the breastworks on the Cravens plateau.

Blue columns could be glimpsed through the chilly fog, steel glinting and flags waving. Nobody could tell exactly how many Yankees were out there across the creek, or where they were heading. “Well, all good times have to come to an end,” thinks Jarman.

Capt. Stegman and his New Yorkers are resting in line of battle when their commander, Col. James Lane, calls them to attention and orders the regiment to deploy as skirmishers. Stegman moves forward through the woods under the direction of Maj. Gilbert M. Elliott. Lane stays several paces behind with the reserves. Lt. Col. Robert Avery, also on the skirmish line, has just returned to action after receiving a nasty neck wound at Chancellorsville. His close friend Maj. Elliot has been on the regimental rolls since the beginning of the war. Since Antietam, however, he has been serving as ordnance officer for Geary's division. Thus, when the bugle sounds the advance, Elliott is leading infantry into battle for the first time in over a year.

To maintain their alignment, the Federals advance slowly through heavy undergrowth. The dense fog limits their visibility and Lane has to halt the skirmishers until he can see the rest of the brigade behind him. After about a mile, a ragged volley from the enemy picket line tears through the air. Elliott orders his men to return fire and Avery rushes back to inform Lane that they are taking heavy fire on their right and left. During this exchange, Elliott goes down with a mortal wound—the first Union casualty of the battle. Avery rushes to his aid, only to be struck by a Minie ball in the leg. The battle has scarcely begun and the 102nd has lost two of its three senior officers.

These losses notwithstanding, the New Yorkers are making headway. According to Lane, it takes all of three minutes to drive the rebels from their position, leaving behind a small camp and some 50 prisoners. Lane sends these to the rear under guard and commits more of his reserve troops to strengthen the skirmish line.

Scattered bangs can be heard south of Robert Jarman’s position. Jets of smoke and flame tear the fog along the banks of the stream. Shouts rise from the skirmishers around the southern-most bridge. They are also men of Walthall’s brigade. Soon enough, they begin to emerge from the haze, running in Jarman’s direction. Some help wounded comrades along. Many are missing.

Huge shells scream overhead. Shrapnel whirls through the picket line. Men dive for cover or join the scramble up the mountain. The steady tramp of feet on pine can be heard to the south. The Yankees have crossed the stream and are making their way up the mountain.

Stegman moves "over those jagged rocks, adown the valleys, pulling by the brushwood, while from every rock and tree the blaze of musketry tells of an alert enemy." They overtake another Confederate camp, probably the pickets' reserve position, and advance to within sight of the "the backbone dividing the north and west sides" of Lookout Mountain. Anticipating the main assault, Lane recalls his skirmishers.

Soon enough, as the fog burns away, Jarman looks south and sees nothing but a long line of sweeping blue. With the Union artillery fire reaching new heights, he decides to fall back towards the main line. He joins a disorganized crowd of several hundred men as they pick their way up through the rocks and brambly trees that cover the face of the mountain.

Robert Jarman emerges into the clearing on the Cravens plateau and looks down the mountain. In a sweeping panorama, he sees countless Yankees hot on his tail. They are scrambling through the trees in loose, aggressive order, more and more crowding behind: “a sight to see.” The battle is being waged at approximately 2,000 feet above sea level. A cloud soon engulfs the struggling parties, limiting visibility to one hundred yards at best. The Mississippi infantry is heavily engaged, sending hundreds and then thousands of Minie balls down the slopes.

Somehow, Capt. Stegman has become separated from the rest of his regiment. He and a dozen of his men join the 60th New York. Ahead, a line of earthworks surrounds a white house. The ground here is relatively flat, the only open ground on the mountain. The New Yorkers press forward "when from thousands of muskets blazed the whirl of death into the face of Geary's ranks." They halt and return fire, then advance in the face of stubborn resistance.

Walthall’s reserves watch expectantly from behind the breastworks. Jarman clambers across the logs and joins his Mississippi comrades as Union cannons across the river begin to bombard the plateau. Solid shot bounds wildly along the fortified line—the guns are outflanking the position. Some of the infantry has to be pulled out of the breastworks and faced south as the Yankee swarm breaks through Walthall’s left flank.

Stegman hears a shout from the right of the Federal formation; “the rebel works are turned, flanked from above, and with one more withering volley, the cry of 'Charge!' rings over the Union line." The New Yorkers surge forward again and scattering southerners are snatched up by the score. Impetuosity infects the 60th and 137th regiments. They chase the rebels into the woods beyond the clearing only to be checked by heavy fire from a new defensive line. They take what cover they can and await reinforcements.

Gradually, Walthall’s men are pushed back to the north, onto the grounds of the Cravens house itself. The Union artillery fire is extremely heavy and the infantry is attacking with proud shouts. Even behind a new line of breastworks, the Confederates are pummeled by repeated charges. Jarman runs away, jumping off of two cliffs “nearly twenty feet high.”

Union reinforcements are not forthcoming. Brig. Gen. Whitaker, commanding the supporting brigade, considers the battle over and has ordered his men to make camp for the night—despite the fact that it is just past noon. Col. Ireland argues with the general, but to no avail. The only aid Whitaker offers is a swig from the "enormous flask" he carries. A frustrated Ireland gives up. Col. Charles Candy's brigade of Geary's division finally comes to relieve Ireland just as a light rain begins to fall. The Battle of Lookout Mountain is over.

Resting near the white house, Capt. Stegman pulls out his diary and scribbles a brief entry: "Up at daylight this morning…Fought hard in front. Very tired." This understatement hardly reflects the dramatic character of the struggle. It also fails to reflect the more than 300 casualties the brigade sustained, or that the 102nd New York lost two of its veteran officers. Later in life, Stegman will describe the Battle of Lookout Mountain in more hyperbolic terms. "More like a story of legendary lore, a weird, wild tale of the annals or fables of the mythological gods than a history of the prowess and daring of the men to-day, men of the living, human present." Hyperbole aside, each man in Geary’s division took immense pride in the part he took in the struggle to relieve Chattanooga.

Walthall’s brigade, “looking more like a regiment” receives orders to evacuate Lookout Mountain late that night. The mountain is soon empty of Confederates and the men are redeployed to Missionary Ridge by midday on November 25. Jarman and his comrades will hold their ground in that day’s assault, but eventually be forced to retreat along with the rest of the army. The Mississippi men had experienced a tumultuous season. After an incredible but costly performance at Chickamauga in September, where they had captured more than a dozen guns, they had endured hunger and the constant tension of siege only to lose the hard-fought battles for Chattanooga. They watch their hopes for decisive victory fade into the distance as they tramp back down the road to Georgia.

Help the Trust save 161 acres across consequential Western Theater battles — Fort Heiman and Fort Henry, Brown’s Ferry/Chattanooga, Spring Hill, and...