Pocahontas is more than a character from a Disney movie. Born around 1597 Pocahontas was the real-life daughter of Powhatan, the paramount chief of a political and spiritual alliance of groups of fellow Algonquian-speaking Virginia Indians. By the time the English arrived in 1607, she likely lived at Werowocomoco, in today’s Gloucester County, Virginia. In Algonquian, Werowocomoco means “place of leadership.” It served as the capital of her father’s chiefdom which spanned Tsenacomoco, which means “densely inhabited place.” The paramount chief Powhatan had many wives and many children, but Pocahontas was his favorite. Pocahontas was a nickname bestowed by her father, meaning “playful one.” More formally she was known as Amonute and Matoaka.

As a young girl, Pocahontas would have learned the traditional skills dictated by her gender. Like other women and girls, Pocahontas would have helped process meat and hides after men returned from the hunt. She would have gathered plants and herbs and weeded and planted gardens for food. She likely knew how to make baskets, pots, and bark mats for bedding, and maybe even helped construct or repair the yehakin she lived in. Like other young girls before puberty, Pocahontas likely wore little to no clothing when she first encountered the English at James Fort.

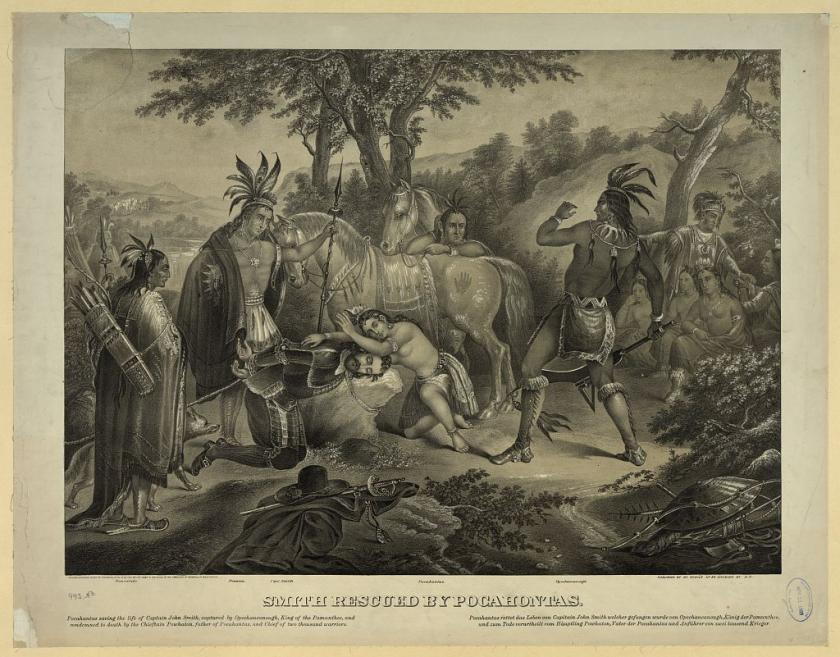

The history of the real Pocahontas is interwoven with the history of English colonization in Virginia, and most of what historians know about her comes from English sources and an English perspective. Famously, Pocahontas appears in the writings of colonist John Smith who (not until 1624) related that in December 1607 he was brought to Werowocomoco after being captured by Powhatan Indians. While there, Smith wrote that Pocahontas saved his life after his head was placed upon a large stone. In Smith’s relation, Pocahontas intervened: “she hazarded the beating out of her own[sic] braines to save mine, and not only that, but so prevailed with her father, that I was safely conducted to James towne.” Some historians question Smith’s version of this event, and importantly, whether it happened at all. Most historians agree that if it did occur, Smith was never in any real danger, and the event likely an elaborate adoption ritual in which Powhatan demonstrated his dominance over Smith, an English representative, who misinterpreted the event entirely.

As relations between the Powhatan and English continued, young Pocahontas accompanied women to James Fort, where they brought food and supplies to the English men living there. In 1608, John Smith described Pocahontas as “a child of tenne years[sic] old, which not only for feature, countenance, and proportion, much exceedeth any of the rest of his [the paramount chief Powhatan’s] people, but for wit, and spirit, the only Nonpariel of his Country.” English settler William Strachey also wrote of Pocahontas’ visits to the fort, and her playful nature with the English boys there. Strachey recalled that Pocahontas would “get the boyes forth with her into the marketplace and make them wheel, falling on their hands, turning their heels upwards, who she would follow and wheel so, herself naked as she was, all the fort over.”

Pocahontas’ interactions with the English were not just for fun and games. As the daughter of the paramount chief, she played a very diplomatic role between the two cultures. On one occasion Pocahontas accompanied her father’s messenger to the fort to negotiate with John Smith for the release of Indian prisoners. Smith “delivered them [to] Pocahontas, for whose sake only, he fained to save their lives and graunt[sic] them liberty.” In January 1609, Pocahontas warned Smith of a plot to ambush him and 18 other Englishmen during a visit to Werowocomoco.

Shortly after, Smith returned to England and Pocahontas disappears from English records until 1613. During that time, the paramount chief Powhatan moved from Werowocomoco to a site on the Chickahominy River, further away from the English at Jamestown. During this time Pocahontas had reached adolescence and accounts suggest that she married an Indian man named Kocoum around 1610. In 1613 Pocahontas was visiting the Patawomeck, a tribe that paid tribute to her father the paramount chief Powhatan, at their town called Passapatanzy. In April of that year, the English Captain Samuel Argall devised a plan to kidnap Pocahontas and hold her for ransom, hoping her father would return English prisoners and stolen tools. Argall received help from Iopassus, the lesser chief of the Patawomeck, who lured Pocahontas onto Argall’s ship. Once onboard Argall refused to let her leave, informing her that he planned to hold her ransom. Argall presented Iopassus with a copper kettle and other gifts, in exchange for his help in the kidnapping plot.

Though Powhatan eventually returned the prisoners Pocahontas remained with the English. Living at Jamestown and then upriver at Henricus, Pocahontas learned the English language and by 1614 had converted to Christianity. When the Anglican Reverend Alexander Whitaker baptized her, she took the name, Rebecca.

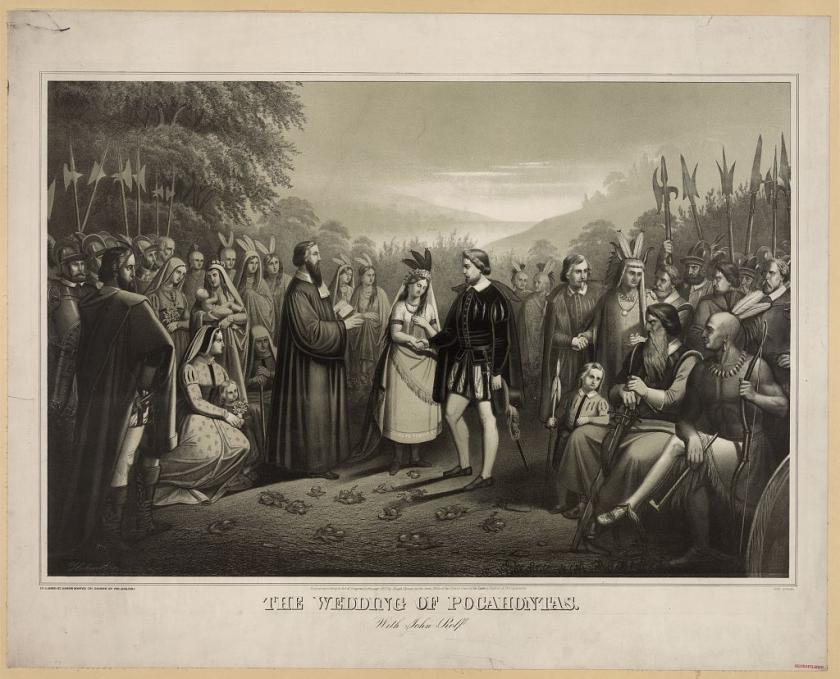

During her time as a captive of the English, Pocahontas met her future husband, John Rolfe. Rolfe had arrived in Virginia after surviving the wreck of the Sea Venture, which left him, his wife, and other colonists shipwrecked on the island of Bermuda for a time. There, his wife gave birth to their daughter, but both mother and child died. The widower Rolfe arrived in Virginia in May 1610. By the time he met Pocahontas, he was experimenting with cultivating tobacco, which would eventually grow to be the colony’s most successful crop. Though the union between an English planter and the daughter of paramount chief Powhatan was undoubtedly useful politically, by his own account Rolfe fell in love with Pocahontas. We have no sources to indicate how Pocahontas felt towards him, but Rolfe’s 1614 letter to Virginia deputy governor Sir Thomas Dale, asking for permission to marry her, reveals his feelings. To Dale, Rolfe wrote of his “hartie and best thoughts” towards Pocahontas, and added he felt “her great appearance of love to me.” Rolfe and Pocahontas married on April 5, 1614, with one of her uncles and two brothers in attendance. Her father approved of the marriage. Sometime later, she gave birth to a son named Thomas. The union ushered in a renewed peace between the English and the paramount chief Powhatan.

It is not known where Pocahontas and John Rolfe lived after their marriage, but by the spring of 1616, they were on board a ship bound for England, to benefit the Virginia Company (the sponsors of the colony at Jamestown). The Company hoped that a visit from Pocahontas would help raise more funds and support for their endeavors in Virginia. Also traveling with the Rolfe family was a small delegation of other Virginia Indians including Pocahontas’s half-sister Matachanna and her husband Uttamatomakkin, whom the paramount chief Powhatan instructed to count all the people in England, among other tasks. Once in London, Pocahontas received new clothes and sat for a portrait by Simon van de Passe, a Dutch artist working in London. In this, the only known image of Pocahontas, she is seen depicted not in her own traditional dress but in the high fashion of the English elite.

While in London, Pocahontas met with King James at White Hall Palace, Queen Anne, and the Bishop of London among others. One Englishman, after meeting Pocahontas, wrote that she “carried her selfe as the daughter of a king,” while others regarded her not as equitable to royalty but simply as “the Virginian woman.” The Rolfes were in the city during the festive Christmas season, and attended a masque (an elaborate play) at King James’ invitation on January 6, 1617. While in England Pocahontas also reunited with John Smith, whom she believed to have died many years before. By Smith’s account, their reunion was not a particularly warm one. When she saw him Smith recalled “without any words, she turned about, obscured her face, as not seeming well contented.”

In March 1617, the Rolfes set sail to return to Virginia. While onboard the ship Pocahontas and her son, Thomas, became ill and the ship anchored at Gravesend just down the shore from London. There Pocahontas died, though the exact cause of her illness is unknown. Her body was interred at St. George’s Church on March 21, as a notation in the church’s burial record indicates: “March 21—Rebecca Wrolfe, wyffe of Thomas Rolfe gent. A Virginian lady borne, was buried in ye chancell.” She was about 20 years old.

Still too ill to travel, Thomas remained in England while his father returned to Virginia. From Jamestown on June 8, 1617, Rolfe wrote, “My wife’s death is much lamented.” In a letter to Sir Edwin Sandys, Rolfe requested that Thomas be sent to Virginia as soon as his strength improved, adding that his son embodied “the lyving ashes of his deceased mother.” Thomas did not return to Virginia until 1635, many years after his father’s death in 1622.

Though the real details of Pocahontas’s life are often clouded with modern interpretations and through the lens of English sources, it is still possible to uncover the real Pocahontas, and appreciate her life and legacy as a daughter, a wife, a mother, and a cultural emissary.

Further Reading:

- Interpreting a Continent: Voices from Colonial America By: John and Kaltheen Duval

- Virginia Indians at Werowocomoco, A National Park Handbook By: Lara Lutz et al.

- Pocahontas’ People: The Powhatan Indians of Virginia Through Four Centuries By: Helen Rountree

- The Powhatan Indians of Virginia: Their Traditional Culture By: Helen Rountree