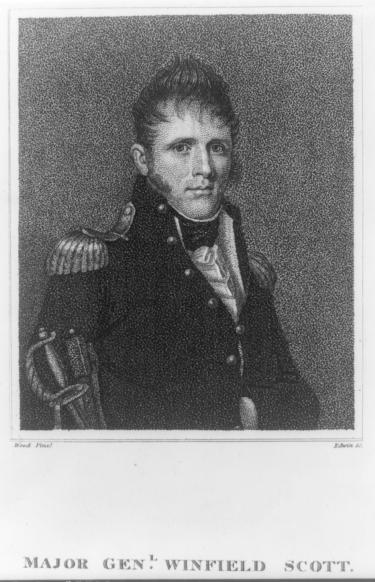

Winfield Scott in the War of 1812

Standing at an imposing six-and-a-half feet tall and being the son of a Revolutionary War officer, Winfield Scott was bound to seek a career in the military. As the tensions between the United States and Great Britain grew in 1807, Scott found himself enlisting in his local Virginian militia cavalry troop where he would first see action. After aiding in the capturing of a boat of British sailors off the coast, Scott became drawn to a life in the military. The following year in 1808, after petitioning President Thomas Jefferson for a commission in the army, Scott was given the position of captain in the elite Regiment of Light Artillery, fulfilling his longing for military service. However, as Scott would bear witness to as he served in the garrison of New Orleans under the command of General James Wilkinson, a Spanish spy with little care for the welfare of his soldiers, the army was in a state of turmoil under incompetent, inexperienced, and outdated leadership. Repulsed by the state of the army and its leaders, the abrasive Scott promptly denounced Wilkinson as a “traitor, liar, and a scoundrel” which would ultimately lead to his court martialing and temporary suspension from duty. The time that Scott spent relieved of his duty would prove invaluable for him as he studied various European military manuals that he hoped to use in the future to modernize and instill discipline on the dilapidated and ill-led army.

Following the declaration of war in June 1812, the now 26-year-old Scott was transferred to the 2nd Regiment of Artillery in Philadelphia where he served as a lieutenant colonel under Colonel George Izard. Scott, a now ardent, demanding, and knowledgeable officer, quickly made a reputation for himself as he drilled his new regiment that quickly became widely considered throughout the army as the most competently led and well-disciplined. Despite his success in implementing modern drill to his regiment, Scott, longing for glory and action on the northern front, received permission in the fall of 1812 to join General Alexander’s Smith brigade in upper New York where preparations were underway for an invasion. Shortly after being transferred, Scott saw action at the ruinous Battle of Queenston Heights on October 13, 1812, where he volunteered to lead the expeditionary force across the Niagara River after his commanding officer was wounded. Although fighting and leading conspicuously, because of petulant disagreements of his superiors, one militia and one regular, Scott was not adequately reinforced and was forced to surrender to save his men from a massacre. After being exchanged as a prisoner of war later that year, Scott was then promoted to Colonel of the 2nd artillery on March 12, 1813, for his leadership in battle despite the failures of his superiors.

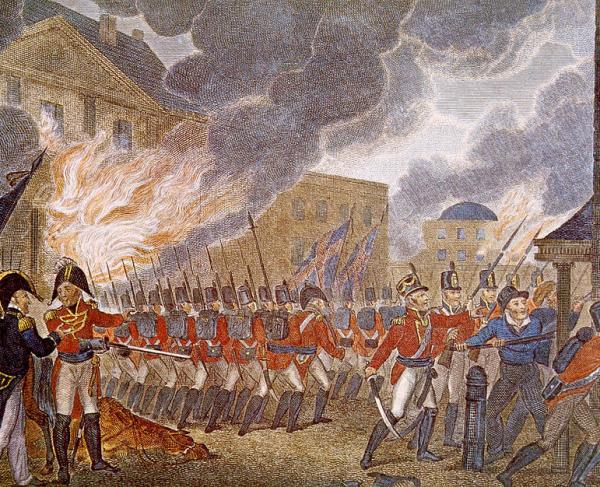

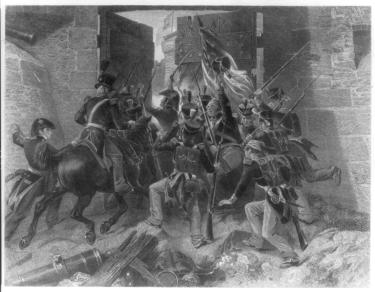

As a well-respected young officer, Scott aided Major General Henry Dearborn as an adjutant on his staff in the following campaign on the Niagara Peninsula in 1813. On May 27, 1813, at the Battle of Fort George, after helping in planning the attack, Scott personally led the first brigade onshore under volleys of fire against a fortified enemy, fighting tenaciously and forcing the British defenders to evacuate their positions. It was here again that Scott would encounter the ineptitude of his outdated, indecisive superiors. Although the retreating British under General John Vincent were greatly susceptible to be cut off and captured, Scott and his soldiers pursuing the defeated enemy were forced to retire after two direct orders from Scott’s superior, General Morgan Lewis, to halt the attack. This failure to seize the initiative would unnecessarily draw out the campaign and lead to more engagements with Vincent’s men, all of which cost the Americans greatly.

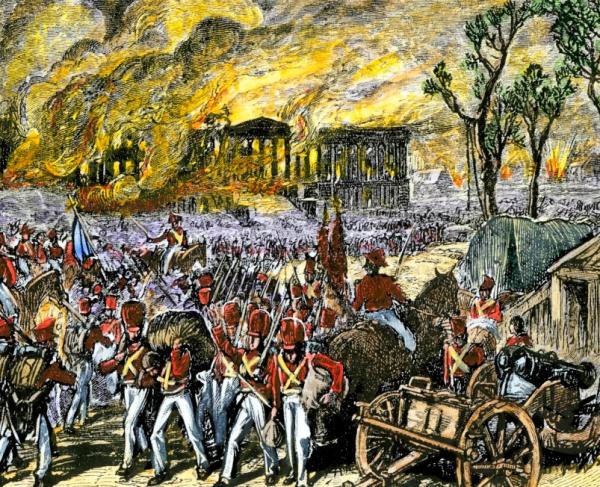

After participating in a brief raid on York, later that year Scott joined the massing regular soldiers under the command of General Wilkinson that was planning to attack Montreal. However, confirming the criticism leveled against him by Scott 5 years prior, Wilkinson bungled the campaign as he ignored the health and discipline of his soldiers while failing to adequately plan his army’s movements, turning what should have been a sure strategic victory into a humiliation of American arms. Following the conclusion of the campaign, appalled by what he saw, Scott returned to D.C. where he reported the dismal state of the army and its command. Impressed by the proactive and eager nature of this young colonel, the Secretary of War John Armstrong bestowed the rank of brigadier general to Scott on March 19, 1814.

Scott, now 28, became the youngest general in the U.S. Army and joined the ranks of a new generation of young determined officers who had distinguished and climbed ranks on merit rather than political favor. It was not long until Scott, now the commander of the 1st Brigade of General Jacob Brown’s Left Division in Buffalo, New York, would see action as a part of another invasion force on the Niagara Peninsula. However, unlike the previously failed expeditions of his archaic and inexperienced predecessors, who took little care in the training or morale of their men, Scott immediately set up a camp of instruction where his regiments could train. For the following 10 weeks, Scott oversaw a rigorous training regimen where his brigade, the 9th, 11th, 22nd, 25th U.S. infantry, and elements of General Ripley’s, the 21st, and 23rd U.S. Infantry, underwent intense drilling under a modern translation of a French drill manual. When the soldiers were not drilling discipline was of the utmost importance, with the strict enforcement of camp sanitation, dress, and military courtesy. By early July 1814, the soldiers under Scott were of a quality of American soldier that had little been seen thus far in the war, able to maneuver and fight with a precision rivaling their British counterparts.

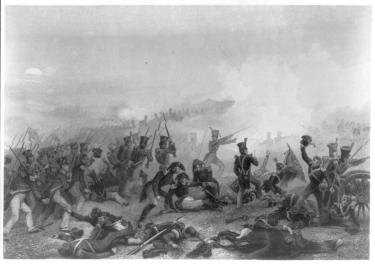

Scott’s drilled men were put to the test on July 5, 1814, at the Battle of Chippawa where his force, in the process of drilling and in parade uniform, was attacked by British General Phineas Riall’s soldiers. Fighting on an open plain in lines, resembling a European battle, Scott decisively defeated his enemy, exchanging disciplined volleys and outmaneuvering the battle-hardened and elite British lines. This feat of arms by Scott marked a turning point in the war in regard to the quality of American soldiers. For the first time in the war, American regulars had stood their ground and defeated British soldiers of an equal number in an open engagement on even terrain. With morale at a feverish high, the Americans advanced further into Canada, engaging the fortified British positions at Lundy’s Lane. Rushing ahead of the rest of the division, the perhaps overly aggressive and encouraged Scott attacked the British defenses directly with his depleted force, causing many unnecessary casualties in the process, including himself, taking a musket ball to the shoulder. While this battle was another testament to the new, hardened discipline of the Americans, it would ultimately end in a stalemate, having incurred dramatic casualties on both sides.

After recovering from his wounds, Scott commanded the 10th military district at Baltimore where he oversaw investigations into officers’ misconduct in battle and the writing of a new drill manual, the first one to be endorsed by the military since the Revolutionary War. Scott’s actions in the War of 1812 and contributions to the professionalization of the U.S. Army, would secure him a revered spot in American military history, and help lay the foundation for a modern, 19th century U.S. Army.

Further Reading

- Agent of Destiny: The Life And Times of General Winfield Scott By: John Eisenhower

- Memoirs of Lieut.-General Winfield Scott By: Timothy D. Johnson

- Life of General Winfield Scott, commander-in-chief of the United States Army By: Edward D. Mansfield