By William L. Shea

Christmas 1861 was the turning point in the Civil War in the trans-Mississippi. On that day, Union Major General Henry W. Halleck placed Brigadier General Samuel R. Curtis in command of the Army of the Southwest and directed him to rid Missouri of Confederate forces. Curtis set his campaign in motion and for the next six weeks his little army struggled across the Ozark Plateau toward Springfield, the principal town in southwest Missouri.

Springfield was occupied by the Missouri State Guard, a pro-Confederate militia under the command of Major General Sterling Price. Curtis had twice as many men as Price, but Price could count on some measure of support from a Confederate army in northwest Arkansas under the command of Brigadier General Benjamin McCulloch. Price and McCulloch had joined to defeat Union Brigadier General Nathaniel Lyon at Wilson’s Creek the previous summer, but after months of bitter wrangling the two generals no longer were on speaking terms and their armies, less than one hundred miles apart, operated independently of one another. President Jefferson Davis attempted to resolve the impasse by placing Major General Earl Van Dorn in charge of all Confederate forces west of the Mississippi River, but before Van Dorn could reach his new command the military situation took a turn for the worse.

As Halleck had hoped, the Confederates were unprepared for the appearance of a Union army atop the Ozark Plateau in the middle of winter. Price abandoned Springfield and retreated south to join McCulloch in Arkansas. Curtis followed, determined to bring the Rebels to battle at the first opportunity. The result was a rare instance of a sustained pursuit of one army by another in the Civil War. The weather turned intensely cold and soldiers and animals in both armies endured snow, sleet, and freezing rain.

The hard-pressed Missourians entered Arkansas on February 16. No one realized it at the time, but the Confederacy suffered an irreversible strategic defeat when Price led his soldiers out of Missouri. Never again would a Confederate army return to that state with a realistic chance of staying. The next morning the Army of the Southwest tramped across the state line and Curtis sent Halleck a triumphant message: “The flag of our Union again floats in Arkansas.”

Price joined McCulloch at Cross Hollows but the two feuding generals were unable to agree on a course of action and continued to fall back across the wintry landscape. The Confederate retreat finally came to a stop in the Boston Mountains, sixty miles inside Arkansas. Curtis halted to consider the situation. He now faced the two largest Confederate armies west of the Mississippi, the same combined force that had overwhelmed Lyon six months earlier. Unwilling to fall back into Missouri and allow the Rebels to regroup, Curtis took a calculated risk and decided to stand his ground just inside Arkansas. He divided his army to facilitate foraging. He occupied Cross Hollows and Brigadier General Franz Sigel’s troops spread out along McKissick’s Creek, twelve miles to the northwest. If the Confederates came storming out of the Boston Mountains, the two wings of the Union army would unite at Little Sugar Creek, a half-dozen miles south of the state line. An imposing line of bluffs behind the stream formed a perfect defensive position.

Van Dorn hurried to the Boston Mountains and assumed command. He converted McCulloch’s army into McCulloch’s division and Price’s army into Price’s division, but made no other changes except to give the combined force a new name: the Army of the West. After conferring with his new lieutenants, he decided to march north, seize the junction at Bentonville, Arkansas midway between the two halves of the Union army, and defeat each half in detail. With Curtis out of the way, the Confederates would return to Missouri and liberate that state from Yankee oppression. Speed and surprise were essential, so Van Dorn stipulated that each Confederate soldier carry only his weapon, forty rounds of ammunition, a blanket, and three day’s rations. Everything else was to be left behind in the Boston Mountains. Van Dorn was so confident of victory that he gave no thought to the possibility that things might go awry.

The Confederate counteroffensive began on March 4, 1862. The 16,000 men and 65 guns of the Army of the West comprised the largest and best-equipped Confederate military force ever assembled west of the Mississippi River. The Confederates had a three-to-two advantage in manpower and a four-to-three advantage in artillery over Curtis’s Army of the Southwest, which numbered only 10,250 men and 44 guns at this stage of the campaign. No other Confederate army ever marched off to battle with a greater numerical superiority.

Unfortunately for the Confederates, the unfolding campaign demonstrated the axiom that numbers alone do not guarantee victory. The march to Bentonville was a disaster. A late winter storm swept across the Ozark Plateau and covered the roads with sleet and snow. The pace of the advance slowed to a crawl and the Confederates suffered immensely. Wrote a Missouri soldier: “It had turned bitter cold. We had no tents and only one blanket to each man. We built log heaps and set them afire to warm the ground to have a place on which to lie, and I remember well the next day there were several holes burned in my uniform by sparks left on the ground.” After two dreadful days and nights in the open, the shivering Confederates ate the last of their rations and set out for Bentonville on March 6. Van Dorn remained confident that his plan to take the Yankees by surprise was working, but Curtis learned of the Rebel counteroffensive and ordered his army to reunite behind Little Sugar Creek.

The Confederates reached Bentonville too late to intercept Sigel’s command, which had passed through the vital junction without serious incident. As the sun set Van Dorn realized that his gambit had failed. The Federals were secure behind a line of hastily-prepared fortifications along Little Sugar Creek while the Confederates were in desperate straits. “Such a worn-out set of men I never saw,” remembered a Louisiana soldier. “They had not one single mouth full of food to eat.” Later that evening Van Dorn learned of a seldom-used road that passed around the right flank of the Union army. Here was an opportunity to snatch victory from the jaws of defeat. Price and McCulloch were aghast at the thought of a night march with everyone in such pitiful condition. McCulloch appealed to Van Dorn “to let the poor, worn-out and hungry soldiers rest and sleep that night . . . and then attack the next morning.” But Van Dorn insisted that the army move at once.

The eight-mile march on Bentonville Detour was a terrible experience for the Army of the West. The snow had stopped but the temperature was lower than the night before. The column shuffled along at a snail’s pace, a pace made slower by massive blockades of trees felled by Union engineers. A third of Van Dorn’s troops fell by the wayside during the seemingly endless march. At dawn on March 7, the head of the Confederate column finally reached Telegraph Road deep in the Union rear. Van Dorn was elated. His army was squarely across the enemy’s line of communications. It was the supreme moment of his career.

Though a victory of Napoleonic proportions seemed to be at hand, Van Dorn was concerned about the attenuated disposition of the Army of the West, which stretched for miles on Bentonville Detour. He told Price, whose division was in the lead, to turn south on Telegraph Road and head toward a rustic hostelry called Elkhorn Tavern. He then directed McCulloch, whose division was in the rear, to turn off Bentonville Detour and proceed toward the tavern on Ford Road. Dividing his command in the presence of the enemy was risky business, but Van Dorn assumed that the Federals were miles away in their fortifications overlooking Little Sugar Creek.

Van Dorn was wrong. Union patrols detected the Confederate flanking movement shortly before dawn. Curtis was methodical by nature and had difficulty grasping the reckless mentality of his opponent. For several hours he remained convinced that the presence of Confederate troops to the north was a diversion and that the primary threat still lay to the south along Little Sugar Creek. Nevertheless, Curtis could not permit even a diversionary force to rampage around in his rear. The fields near Elkhorn Tavern were crowded with hundreds of supply wagons. Curtis decided to keep two-thirds of his army at Little Sugar Creek and send the remainder to intercept the Confederates and keep them away from his trains.

Curtis dispatched Colonel Peter J. Osterhaus to the northwest to intercept McCulloch’s column. Shortly after noon Osterhaus emerged from a belt of trees north of the hamlet of Leetown and gazed in wonder across a snow-covered prairie. Directly ahead was McCulloch’s division moving east on Ford Road with flags flying and weapons gleaming in the midday sun. Osterhaus was shocked. He seemed to have stumbled upon half of the Confederate army! Despite being hopelessly outnumbered, Osterhaus ordered his artillery to fire on the tightly packed Rebel formation.

Surprised, McCulloch responded with a massive cavalry charge. Osterhaus fell back toward Leetown and formed a line along the south side of a large cornfield. McCulloch now made the critical decision to halt his eastward movement and deploy his entire division to the south against Osterhaus. This meant, of course, that the reunion of the Army of the West at Elkhorn Tavern would be delayed. Confident of success, McCulloch rode forward to reconnoiter the Union position. It was a fatal error. He stumbled across a skirmish line of soldiers from the 36th Illinois in the belt of trees. The Federals fired a ragged volley and McCulloch tumbled to the ground.

No one in the Confederate army saw McCulloch fall. He seemed to have vanished into thin air. For an hour, thousands of troops remained immobile, awaiting orders to advance. Command eventually passed to Brigadier General James M. McIntosh, who impulsively rode forward to see the lay of the land for himself. The skirmishers of the 36th Illinois loosed another volley and knocked McIntosh out of his saddle. He and McCulloch died in an identical fashion only 200 yards apart. The confusion that resulted from their deaths kept most of McCulloch’s division out of the fight.

The next ranking officer of McCulloch’s division was Colonel Louis Hébert. Impatient at the delay and unaware that he now was in overall command, Hébert advanced on his own through the woods to the east of the cornfield. By this time Osterhaus had been reinforced by Colonel Jefferson C. Davis, whose command bore the brunt of Hébert’s assault. The fight in the woods was intense. A Union soldier recalled that the air around him was “literally filled with leaden hail. Balls would whiz by our ears, cut off bushes closely, and even cut our clothes.” Hébert blundered into Union lines in the smoky woods and was captured, completing the decapitation of McCulloch’s division. Stiffening Union resistance in front and flank caused the Confederates to withdraw. By late afternoon the fighting near Leetown sputtered out and the leaderless officers and men of McCulloch’s division milled around and waited for someone to tell them what to do. As darkness fell some regiments drifted away and returned to the Boston Mountains. Others followed the Bentonville Detour and joined Price’s division. Without food or rest for two days and nights, they played no further role in the fight.

While McCulloch’s division unraveled near Leetown on March 7, a larger engagement raged two miles to the east near Elkhorn Tavern. After Curtis sent Osterhaus to the northwest to intercept McCulloch, he dispatched Colonel Eugene A. Carr to the northeast to block Price’s column. Carr reached Elkhorn Tavern about thirty minutes ahead of the Confederates and deployed his command at the head of a gorge called Cross Timber Hollow. Price’s division, personally led by Van Dorn, soon plowed into Carr’s troops and a firefight erupted. Up to that moment Van Dorn believed that his march on Bentonville Detour had gone undetected and that the Federals were still in their fortifications behind Little Sugar Creek. Surprised and possibly unnerved by the presence of Union troops so far north, Van Dorn told Price to “move forward carefully.” It was the most uncharacteristic order he ever issued. Skirmishing and artillery duels filled up the afternoon. There was barely an hour of daylight remaining when Van Dorn finally ordered a general assault.

The Confederate attack started off well enough but the formations gradually disintegrated into smaller and smaller parts, with each regiment, battalion, or even company advancing uphill at its own pace and on its own course. The Union defenders fought from behind whatever cover was available. “Each man sought a tree, a stump or a rock, loaded and fired as rapidly as he could,” recalled an Iowa infantryman. The Confederates faltered just short of the crest and for a few moments it appeared that Carr’s troops might hold their position, but the crush of numbers was too great.

Overwhelmed in front and on both flanks, the Union regiments around Elkhorn Tavern fell back through a maze of fences and outbuildings. Now the only Union presence was a hodgepodge of guns from different batteries arrayed in a semi-circle on Telegraph Road. The artillerymen worked frantically to limber up their weapons and escape. In a final act of defiance they fired a ragged salvo of canister into the faces of the oncoming Confederates. Stunned survivors of the murderous blast stumbled forward and captured two of the smoking guns, but the Federals took advantage of the chaos and rolled to safety with all of their other guns and caissons.

Carr regrouped in the twilight a half-mile south of the tavern in a large cornfield. The Confederates emerged from Cross Timber Hollow onto the high ground around Elkhorn Tavern. Van Dorn searched to the west along Ford Road but there was no sign of McCulloch’s division. By now he knew of McCulloch’s death but failed to grasp the dimensions of the disaster that had befallen McCulloch’s command. Daylight was fading fast so Van Dorn ordered an immediate frontal assault against Carr’s position. Three thousand Confederate soldiers surged across the snow-covered field. At this critical juncture Curtis arrived with fresh troops and additional guns from Little Sugar Creek. The Union reinforcements filed into line with only moments to spare; the Confederates were approaching, “their cheers and yells rising above the roar of artillery.” But not for long. Blasts of canister from Union guns lined up wheel to wheel plowed dreadful lanes through the ranks of the oncoming Rebels. Despite the mounting slaughter, Price’s men pressed on. “By this time it was almost dark,” remembered one of the Missourians, “and we got so near the battery that the fire from the guns would pass in jetting streams through our lines.” When the Confederates finally staggered to a halt less than fifty yards from Carr’s position, the Union infantry rose up and fired. The ghastly affair was over in fifteen minutes. Survivors of the doomed assault streamed back to Elkhorn Tavern while the Federals cheered and jeered in triumph. The twilight attack on March 7 was the high water mark of the Confederate war effort west of the Mississippi River.

During the night Curtis concentrated the Army of the Southwest into a compact mass. He abandoned the Little Sugar Creek fortifications and reinforced Carr’s position on Telegraph Road. He also saw to it that food, water, and ammunition were distributed. By dawn on March 8 the Union army was ready for a second day of battle. Van Dorn attempted to do the same with the Army of the West but was less successful. The Confederates were without food except for what was found in Federal haversacks and sutlers’ wagons. They also were without adequate ammunition, for in the confusion of the march on Bentonville Detour the previous night, the ammunition train had been left behind. No one at Confederate headquarters knew where the ammunition train was and no one thought to organize a search until the next morning.

When dawn broke on March 8 without any activity on the Confederate side of the field, Curtis realized that he held the initiative. He turned to Sigel and told him to prepare the way for an infantry assault. For what may have been the only time in the Civil War, Sigel was in his element. He assembled the Union artillery and unleashed the most intense bombardment of the war up to that time. The tremendous noise could be heard fifty miles away in Fayetteville and Springfield. “It was the grandest thing I ever saw or thought of,” exclaimed an Iowa officer. The devastation wrought by shrapnel and splinters on Confederate soldiers huddled in the woods around Elkhorn Tavern was terrible. Hundreds of wounded, dazed, or terrified soldiers fled to the relative safety of Cross Timber Hollow.

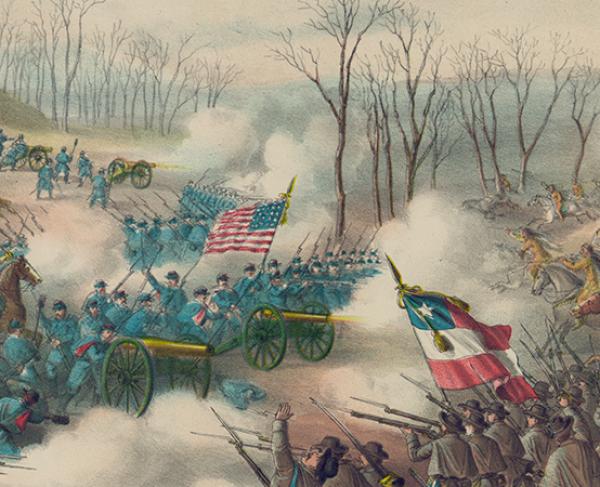

After two terrible hours the Union guns fell silent and the infantry advanced. The curving blue line stretched nearly a mile from flank to flank. An Indiana surgeon described the imposing martial array as “the grandest sight that I had ever beheld.” As drums rolled and bugles rang, the Federals converged on Elkhorn Tavern from the west and south. “That beautiful charge I shall never forget,” wrote an officer in an Illinois regiment. “With banners streaming, with drums beating, and our long line of blue coats advancing upon the double quick, with their deadly bayonets gleaming in the sunlight, and every man and officer yelling at the top of his lungs. The rebel yell was nowhere in comparison.”

Van Dorn ordered a retreat and hurried away to the east, leaving thousands of his men on the field fighting a hopeless rear guard action. Without food or shelter, the Confederates suffered terribly during a week-long trek to the Arkansas River. Curtis did not pursue. He settled down to inter the dead and care for the wounded of both armies. Union casualties amounted to more than 200 dead and well over 1,000 wounded. Confederate losses were substantially higher but an exact accounting is impossible.

Rattled by his failure to defeat Curtis and liberate Missouri, Van Dorn abandoned Arkansas and transferred his army to the east side of the Mississippi, where he arrived too late to take part in the Battle of Shiloh. A few weeks after Pea Ridge Curtis resumed his push into Arkansas and ultimately reached Helena on the west bank of the Mississippi, six months and seven hundred miles from his starting point in Missouri. It was the deepest penetration of the Confederacy yet and Curtis was justly proud of that fact that his little army was “farthest south.” Pea Ridge was not a particularly large engagement but its impact was immense. When the smoke cleared from that frosty battleground atop the Ozark Plateau, Missouri was secure for the Union, much of Arkansas was lost to the Confederacy, and the balance of power in the West was forever altered.