Johnston County, NC | Mar 19 - 21, 1865

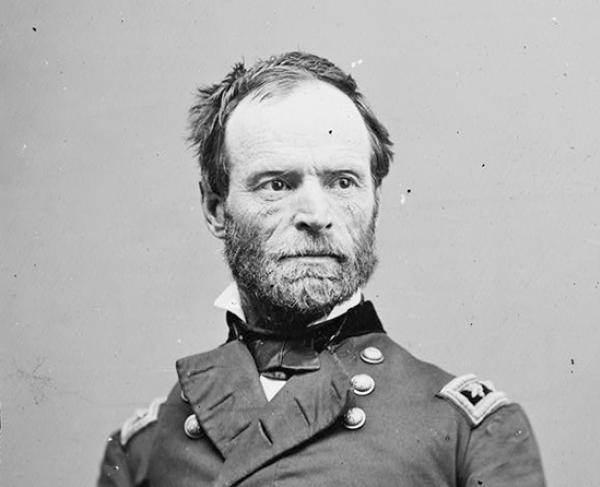

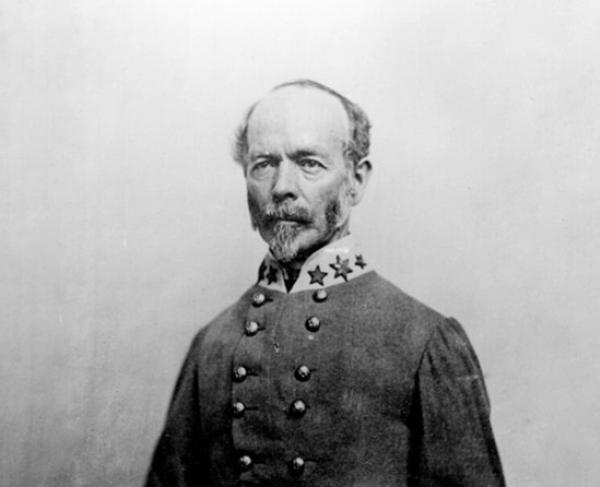

From March 19-21, 1865, Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston and what remained of the Confederate army attacked and were defeated by Union General William T. Sherman’s army in the Battle of Bentonville, the last large-scale battle of the Civil War.

How It Ended

Union Victory. After fighting to a standstill on the 19th and skirmishing throughout the 20th, Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston decided to stay on the battlefield with what remained of his army. However, by the 21st, elements of Union Bvt. Major General Joseph A. Mower’s division threatened Johnson’s left flank and his route of retreat. After pushing back Mower’s division, Johnston decided to retreat from the field during the night, ending the battle. After his defeat, Johnston and his army moved further into North Carolina and surrendered a month later at Bennett Place.

In Context

In early 1865, General William T. Sherman’s army moved out of Georgia and into the Carolinas. To slow him down, President Jefferson Davis tasked General Joseph E. Johnston with collecting what remained of the Confederate army in the south and fighting Sherman somewhere in North Carolina.

Following his March to the Sea, Union Major General William T. Sherman drove northward into the Carolinas, splitting his force into two wings: Major General Henry W. Slocum commanded the Left Wing, while Major General Oliver O. Howard commanded the Right. The plan was to march through the Carolinas, destroying railroads and disrupting supply lines before joining Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant’s armies near Richmond. However, on March 16, 1865, Slocum’s wing was slowed by Lieutenant General William Hardee’s corps at Averasboro, North Carolina, where after a day of heavy fighting, the Confederates withdrew.

On March 19, as the respective wings approached Goldsboro, General Henry W. Slocum's wing encountered Confederates of General Joseph E. Johnston's army, who had concentrated at Bentonville with the hope of slowing the Union’s advance.

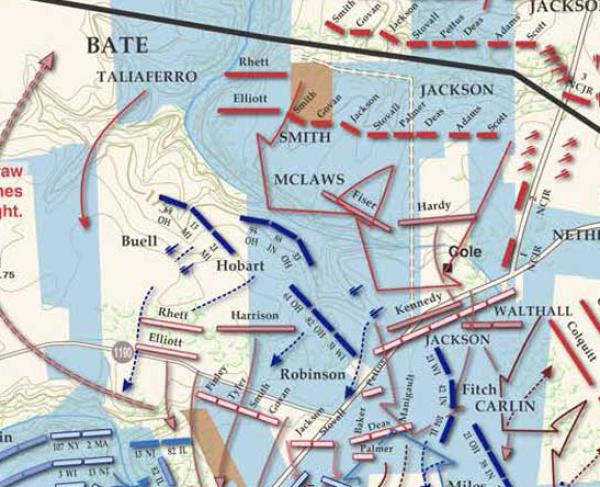

Convinced that he faced only a small Confederate cavalry force, Slocum launched a probing attack which was quickly driven back. In the late afternoon, a Confederate trap was sprung. A division of Southern infantry under Hardee attacked, driving Slocum's men back. However, James D. Morgan's Union division held out against the onslaught, and eventually, Union reinforcements arrived. The Confederates reached their high-water mark of the battle at the Morris Farm, where Union forces formed a defensive line. After several Confederate attacks failed to dislodge the Union defenders, the weary Confederates pulled back to their original lines. Nightfall brought the first day's fighting to a close in a tactical draw.

On the 20th, General Oliver O. Howard's right-wing arrived to reinforce Slocum, which put the Confederates at a numerical disadvantage. Sherman expected Johnston to retreat and was inclined to let him do so. Although Johnston began evacuating his wounded, he refused to give up his tenuous position, guarding his only escape route across Mill Creek. Though outnumbered, Johnson's only hope for success was to entice Sherman into attacking his entrenched position, something Sherman was unlikely to do. A few sporadic skirmishes occurred throughout the day, but no significant action ensued.

On the 21st, Johnston remained in position, and skirmishing resumed. That afternoon, Union Bvt. Major General Joseph A. Mower led a "little reconnaissance" toward the Mill Creek Bridge under heavy rainfall. When Mower discovered the weakness of the Confederate left flank, that little reconnaissance became a full-scale attack against the small force holding the bridge. A Confederate counterattack, combined with Sherman's order for Mower to withdraw, ended the advance, allowing Johnston's army to retain control of their only means of supply and retreat.

1,527

2,606

Knowing that Sherman could easily threaten his supply lines and his only avenue of retreat, Johnson decided to retreat from the battlefield and head toward Smithfield. Sherman chose not to pursue Johnson and moved on to Goldsboro. After regrouping, Sherman pursued Johnston’s army toward Raleigh. On April 26, Johnston formally surrendered his army.

During William T. Sherman's march through the Carolinas, he divided his armies into two wings to cover more ground. Realizing that their forces were divided, Johnston decided to attack one of Sherman’s wings, hoping to tip the scales in his favor. By mid-March, Johnson decided to attack Union General Henry W. Slocum's wing at Bentonville. Unfortunately for Johnson, Union reinforcements arrived from Oliver O. Howard's wing after two days of fighting, causing Johnson to be significantly outnumbered.

After threatening Johnson's line of retreat near Mill Creek Bridge, Sherman held his men back long enough for the Confederates to slip out and retreat towards Adairsville. However, Sherman and his army were completely unaware of this move and discovered the Southern army had fled by the morning of the 22nd. As a result, Sherman decided to move on toward Goldsboro, where he linked up with Alfred Terry's and John M. Schofield's commands. From there, he marched towards Raleigh, ultimately forcing Johnson to surrender at Bennett Place.

Bentonville: Featured Resources

All battles of the Carolinas Campaign

Related Battles

60,000

21,000

1,527

2,606