Chattanooga

Missionary Ridge, Lookout Mountain

Hamilton County and City of Chattanooga, TN | Nov 23 - 25, 1863

The Federals’ victory at Chattanooga opened up the Deep South for a Union invasion and set the stage for Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s Atlanta Campaign the following spring.

How it ended

Union victory. After the battles, the rivers, rails, and roads of Chattanooga were firmly in Union hands. The city was transformed into a supply and communications base for Sherman’s 1864 March to the Sea.

In context

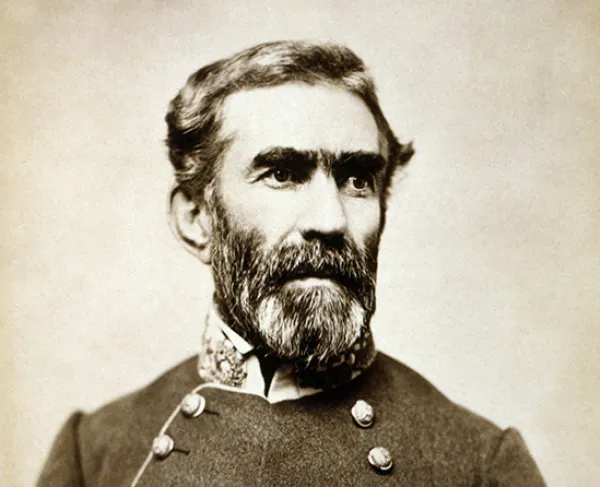

Following Union general William Rosecrans’s defeat at Chickamauga on September 18–20, 1863, the Army of the Cumberland fell back to the high ground and rail hub at Chattanooga, Tennessee. Confederate general Braxton Bragg chose to besiege the Union forces entrenched around the city, hoping to starve them into surrender.

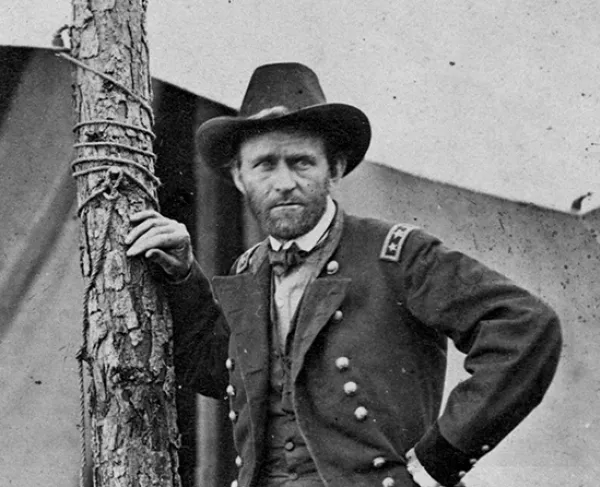

In October, Gen. Ulysses S. Grant was given command of all Union forces in the west and replaced Rosecrans with Maj. Gen. George Thomas. After securing the vital “Cracker Line” to feed his starving army and defeating the Confederate counterattack at Wauhatchie, Grant turned his focus to a Union breakout.

The three-day Battles of Chattanooga resulted in one of the most dramatic turnabouts in American military history. When the fighting stopped on November 25, 1863, Union forces had driven Confederate troops away from Chattanooga, Tennessee, into Georgia, clearing the way for Union general William T. Sherman's March to the Sea a year later. Sherman wreaked havoc as his troops blazed a path of destruction, burning towns between Atlanta and Savannah in an effort to cripple the South.

Distraught at his devastating loss at the Battle of Chickamauga in September, Union general William Rosecrans retreats to Chattanooga, Tennessee. Confederate general Braxton Bragg, looking to capitalize on his victory against Rosecrans, follows the Federals there and establishes positions on Missionary Ridge and Lookout Mountain, successfully putting the Union troops under siege and cutting off their supply line.

On October 17, Gen. Ulysses S. Grant is given command over the newly created Military Division of the Mississippi, which puts all Federal troops in the Western Theater—including the Army of the Cumberland—under his control. In the days that follow, Grant learns that Rosecrans is planning to withdraw the Army of the Cumberland from Chattanooga, effectively surrendering the strategically important city. Grant immediately replaces Rosecrans with Maj. Gen. George Thomas and orders Thomas to hold Chattanooga, to which Thomas responds, “we will hold the town till we starve.” In an effort to send support to the men of the Army of Cumberland, Grant sets up a “Cracker Line” to move food across the Tennessee River to the soldiers under siege.

November 23. Grant receives word from Confederate deserters that Bragg is withdrawing some of his brigades. On seeing columns of Confederates marching away from Missionary Ridge, Grant becomes concerned that Bragg is sending troops to reinforce the Confederates under Lt. Gen. James Longstreet near Knoxville. In an effort to prevent this, Grant sends 14,000 Union troops to engage a rear-guard of 600 Confederates at Orchard Knob. The vastly outnumbered Rebels are able to get off only one volley before being overrun by the Federals. Orchard Knob serves as Grant’s headquarters for the remainder of the battle.

November 24. Major General Joseph Hooker strikes the Confederate left at Lookout Mountain. Hooker has three divisions under his command, which are led by generals John W. Geary, Charles Cruft, and Peter J. Osterhaus. At 10:30 a.m., Geary’s men make contact with Confederate general Edward Walthall’s men one mile southwest of Point Lookout. The Confederates’ inferior numbers are quickly driven back. At 1:00 p.m. Confederate general John C. Moore launches a counterattack against the surging Union forces, but the Rebels find themselves severely outflanked and retreat through the fog. That night, Bragg holds a council with his generals and decides to withdraw from Lookout Mountain to reinforce Missionary Ridge. This hands Grant a second victory.

Although Grant expects Gen. William T. Sherman to attack Missionary Ridge in coordination with Hooker’s attack at Lookout Mountain, faulty intelligence leads Sherman’s men to Billy Goat Hill instead. Undaunted, Grant is determined to follow up the success of November 24 with a coordinated effort. Hooker will advance on Missionary Ridge from the south while Sherman attacks Tunnel Hill, on the northern end of the Confederate position. Thomas’s Army of the Cumberland is arrayed against the center of Bragg’s line to offer assistance as needed.

November 25. Sherman’s men experience early successes, but a counterattack from the Confederates routs the exhausted Federals. The attack on Tunnel Hill comes to a halt at 4:00 p.m. On the Confederate left, Hooker finds more success than Sherman. After arriving at Rossville Gap, the southernmost point of Missionary Ridge, Hooker launches a three-pronged attack that leaves the surprised Confederate troops surrounded. They quickly surrender. At 2:30 p.m. Grant orders Thomas to demonstrate against the Confederate center and draw Bragg’s attention away from Sherman. Thomas deploys 24,000 men against rifle pits at the base of the Ridge. The Union soldiers charge against the pits and successfully overrun the 9,000 defenders. Despite Grant’s orders to the contrary, Thomas’s men continue their charge, swarm over the ridge, and overwhelm the Confederates. With no tactical reserve in place, the thinly manned Confederate line breaks and flees from Missionary Ridge, ending the siege of Chattanooga.

5,824

8,000

The Confederates retreat from Chattanooga with the Federals in pursuit. The two armies meet up again at Ringgold Gap on November 27, where Confederate general Patrick Cleburne surprises and stops Hooker’s larger force. After Cleburne’s stunning defense, which allows the Confederate wagons and artillery to pass through the gap unharmed, Grant decides to abandon the chase.

The "Cracker Line" was a Union supply line which crossed the Tennessee River twice on pontoon bridges and fed a starving force.

After their defeat by Confederate general Braxton Bragg in September 1863 at Chickamauga, the Union Army of the Cumberland fled to nearby Chattanooga. Bragg followed and took up positions on Lookout Mountain and Missionary Ridge, obstructing Union supply lines on the Tennessee River. The lack of rations quickly began to take its toll on the besieged Union troops in the city, as well as on their horses and mules, many of which began to die from starvation. Ample supplies in Bridgeport, Alabama, were available to move to the Union troops trapped in Chattanooga, but they were 60 miles away by land and the roads were muddy and impassable.

When Grant arrived in Chattanooga on October 23, he was approached by the Chief Engineer of the Army of the Cumberland, Brig. Gen. William “Baldy” Smith, with a brilliant amphibious-land solution. Smith proposed building a bridge across the Tennessee River to establish a “Cracker Line”—a reference to the notoriously hard crackers called hardtack. His idea involved using flat-bottomed boats to transport men down the river, just under the Confederate guns on Lookout Mountain. Once they passed the guns, they would land on the left bank of the river and establish a bridgehead there, while additional troops paddled across the river from the right bank. With a crossing point firmly established, Thomas’s troops would link up with men from the Eleventh and Twelfth Corps under Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker, who were marching toward Chattanooga from the southwest. It was daring but doable, and Grant approved it.

On October 27, Union forces repulsed the Fifteenth Alabama to seize the beachhead at Brown’s Ferry. Smith's engineers then began building a bridge across the river, which was completed by sunset. Hooker's column marched through Lookout Valley and arrived at Brown's Ferry at 3:45 p.m. on October 28. By October 29, the first supplies along the Cracker Line reached Chattanooga, improving the outlook for the enlisted men trapped there. Once the troops’ rations were assured, Grant authorized the transport of additional munitions. By the middle of November, the men were resupplied and ready to begin an offensive against Bragg.

With Sherman’s and Hooker’s corps stalled at Missionary Ridge on November 25, Grant turned to Thomas, ordering him to advance on the Confederate rifle pits. The instructions were conveyed quickly and verbally. The troops were to approach the enemy’s rifle pits and halt there to await further orders.

At 3:40 p.m., four divisions of Thomas’s army, about 24,000 men, marched toward the line of Confederate rifle pits at the base of Missionary Ridge. Despite the barrage of Confederate artillery from the top of the ridge, Thomas’s soldiers easily made it to a point just in front of the rifle pits. But suddenly, the Rebels in the lower line of breastworks began running up the slope. By the time the Federals approached, half of each division was already at the top of the ridge, leaving the remainder to climb up under fire, with their backs exposed to the enemy.

Thomas’s men believed the Rebels were retreating in terror. They paused at the rifle pits as ordered, when enemy gunfire from top of the ridge began raining down on them. To stay in the rifle pits would mean sure death for the men trapped there with no cover. With no options, they defied command, instinctively charging up the slope toward the top of the ridge while firing at the Rebels ahead of them.

Watching this horrific scene through field glasses from Orchard Knob, Grant, demanded to know who ordered the charge. “I don’t know,” replied Thomas. “I did not.” The Federals continued to sweep over the crest of the ridge to the horror of the Rebels, who didn’t have a clear field of fire and were afraid of hitting their own men. With their artillery rendered ineffective, they eventually panicked and fled. The Confederate line was destroyed.

Thomas’s veteran troops had won a battle against all odds, and Grant, impressed by the mettle of the men, earned a lucky victory. It wasn’t military prowess that saved the day, but resilience in the face of chaos and the basic instinct for survival. The Confederates were less fortunate. They had a hard time explaining what went wrong at Chattanooga. The blame ultimately fell on Gen. Bragg, who resigned from his army command on November 30.

Chattanooga: Featured Resources

All battles of the Chattanooga-Ringgold Campaign

Related Battles

72,500

48,900

5,824

8,000