Fort Wagner

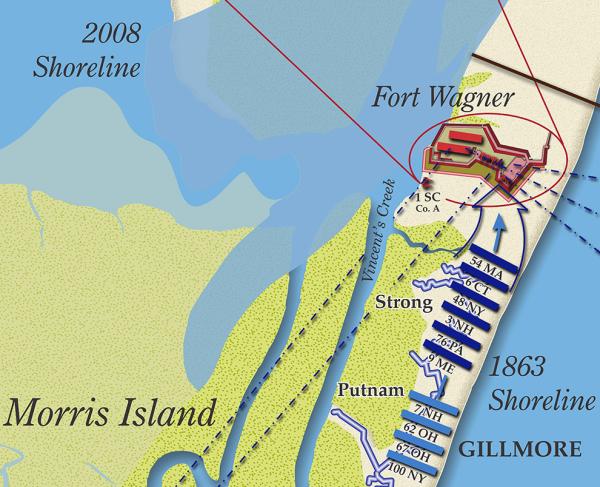

Battery Wagner, Morris Island

Morris Island, SC | Jul 18 - Sep 7, 1863

The Battle of Fort Wagner on July 18, 1863, was an unsuccessful assault led by the 54th Massachusetts, an African American infantry, famously depicted in the movie Glory. Fort Wagner is located on Morris Island in the Charleston Harbor, South Carolina.

How It Ended

Confederate Victory. While the 54th Massachusetts Infantry and nine other regiments in two brigades successfully scaled the parapet and entered Fort Wagner, they were driven out with heavy casualties and forced to retreat. Unconvinced of the success of frontal assaults, the Federals resorted to land and sea siege operations to reduce the fort over the next two months. After 60 days of shelling and siege, the Confederates abandoned Fort Wagner on September 7, 1863.

In Context

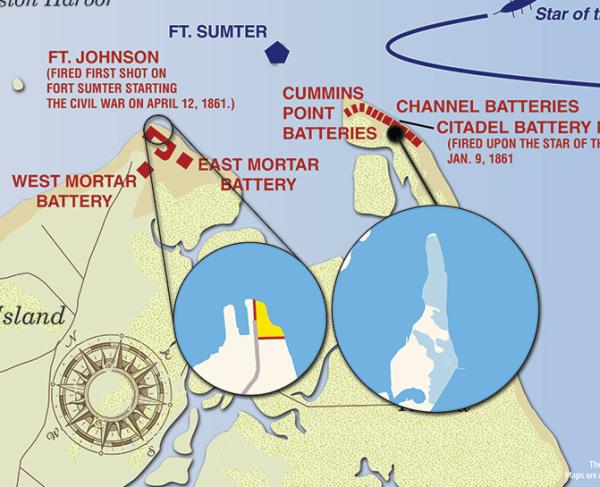

Charleston, South Carolina, was the site of the opening engagements of the Civil War when newly created Confederate forces fired upon Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor and forced Federal soldiers to abandon the fort. Since then, the city has stood as a symbol of secession for Northerners and the birthplace of independence for Southerners. While not necessarily a strategically important city, Northern forces hoped that taking the city could boost Northern morale while demoralizing the South.

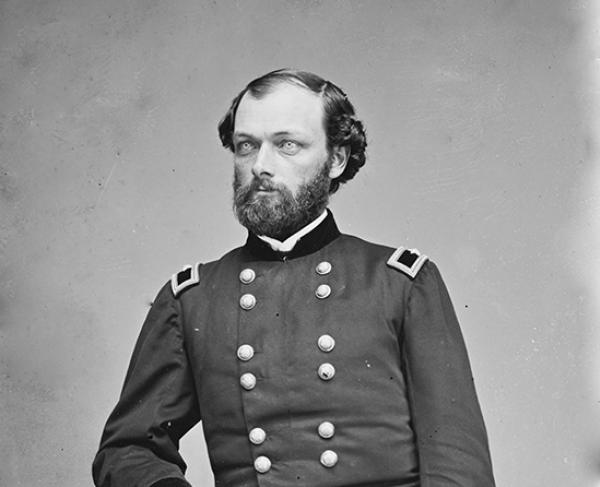

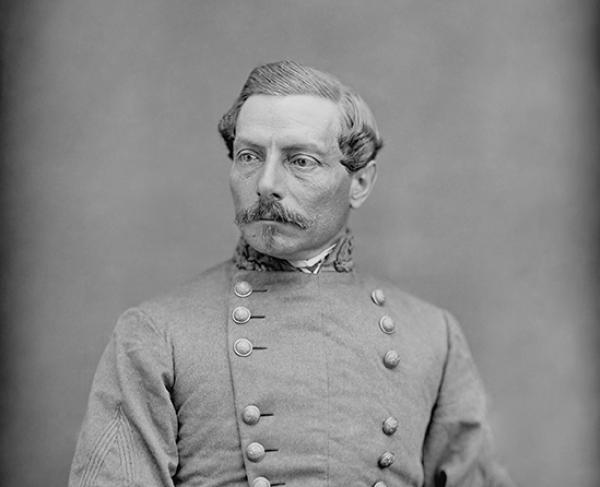

After the successful amphibious operation against Port Royal, South Carolina, and the stunning, long-range artillery bombardment that led to the swift capture of Fort Pulaski, Brig. Gen. Quincy Gillmore was assigned to lead the 1863 campaign against the city of Charleston. Supported by a heavy naval presence in Charleston Harbor, Gillmore's planned to seize Morris Island, which held Fort Wagner and Fort Gregg, and place heavy rifled guns on Cummings Point to neutralize Fort Sumter. Once the Federals overtook Sumter, then the army and the navy could move undisturbed into the city.

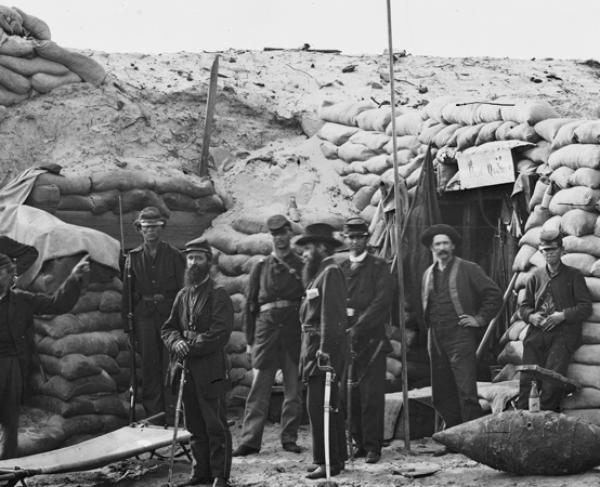

Fort Wagner, also known as Battery Wagner, was a sand and earthen fortification located on the northern end of Morris Island outside Charleston, South Carolina. Fort Wagner, and Fort Gregg nearby, covered the southern approach to Charleston Harbor. It was considered one of the toughest beachhead fortifications due to its location near a natural bottleneck that restricted soldiers from engaging the fort en masse.

On July 10, Brig. Gen. Quincy Gillmore instructed Brig. Gen George C. Strong to launch a surprise amphibious landing on the southern end of Morris Island to begin weakening the fort. By late afternoon, the intrepid Strong had routed the island's defenders back to their strongholds at Wagner and Gregg. Strong's men took 150 prisoners, a dozen guns, and five flags. The next day, on July 11th, Strong's regiment attacked again but was repealed by the Confederate forces.

Since the Federals conducted the first two assaults without artillery support, Gillmore decided to strike again with one of the war's heaviest cannonades to date with the Federal fleet in Charleston Harbor. This fleet included the USS New Ironsides, a veritable floating gun platform sheathed in iron, and ten other ships. The shelling would commence on the morning of July 18, 1863.

Four Federal land batteries opened fire at 8:15 a.m., and soon 11 ships of Col. Ulric Dahlgren's fleet were adding their salvos to the massive bombardment. Confederate forces, led by Brig. Gen William B. Taliaferro (pronounced Tolliver) covered the fort's artillery with sandbags to protect them from the shelling and sought shelter in the fort. Taliaferro instructed Lt. Col. P.C. Gaillard's Charleston battalion to main the ramparts throughout the day. As the tide rose in the afternoon, the ships advanced and launched shells that weighed more than 400 pounds onto Morris Island.

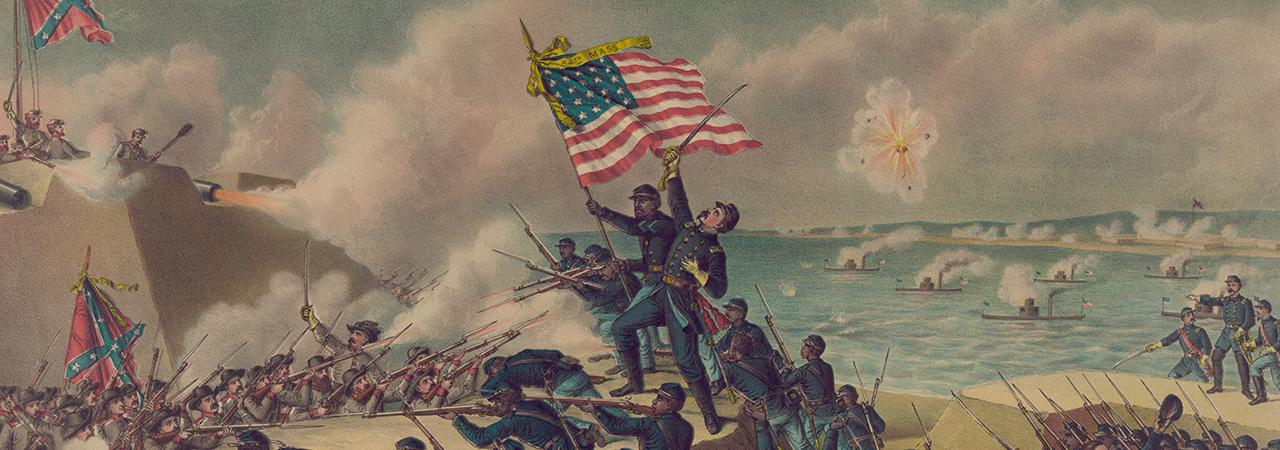

At sunset, the 54th Massachusetts Infantry, and African-American infantry, led by Col. Robert Gould Shaw, advanced on Fort Wagner for a frontal assault as the naval assault ceased. When the Federal forces were within 150 yards of the fort, Taliaferro instructed his soldiers to fire. As he crested the flaming parapet, Shaw waved his sword, shouted "Forward, 54th!" and then pitched headlong into the sand with three fatal wounds. Strong's brigade and Col. John L. Chatfield 6th Connecticut joined the fray. Soldiers of the 48th New York succeeded in following the Connecticut troops up the slopes of the southeast bastion, but few of Strong's remaining units were able to get that far. Three Confederate howitzers had come into action on the flanks of the attacking forces. The deadly hail of canister brought the 3rd New Hampshire, 76th Pennsylvania Zouaves, and 9th Maine to a bloody standstill atop a ridge of sand just beyond Wagner's moat.

As the 100th New York Regiment approached the fort, they mistakenly fired onto the ramparts, trapping several Federals regiments between two sides of gunfire. While several more Federal regiments were able to reach the fort, others were not forthcoming. With a lack of reinforcements, Major Lewis Butler began an evacuation of Federal forces. By 10:30 p.m., the desperate fight for Fort Wagner was over, and the Confederates still held the fort.

1,515

174

Federal forces sustained heavy losses, and Gillmore realized that Fort Wagner could not be taken by a direct assault. Instead, Gillmore began a land and sea siege of the fort. After 60 days of shelling and siege, the Confederates abandoned Fort Wagner and Fort Gregg nearby on September 7, 1863. After Morris Island came into Federal control, they heavily bombarded Fort Sumter. However, Fort Sumter, and Charleston, didn't surrender. It wasn't until General William T. Sherman advanced through South Carolina, after his March to the Sea in Georgia, that Confederate forces abandoned Fort Sumter on February 17, 1865, and Charleston the next day.

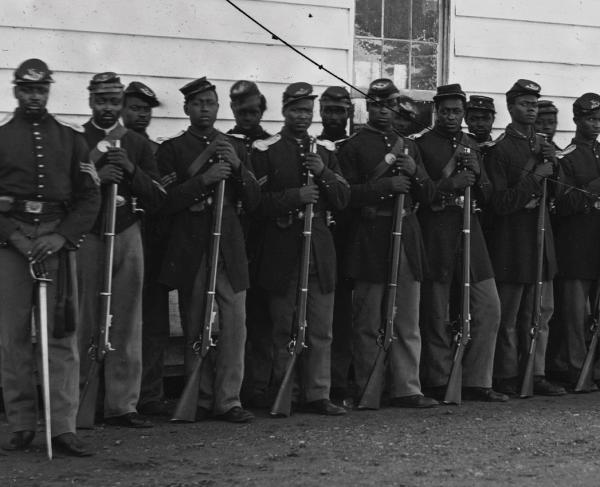

While the Battle of Fort Wagner was a Confederate victory, this battle showed the fierce determinations of African Americans in the Union army with the brave assault led by the 54th Massachusetts Infantry. For their valor, numerous soldiers, such as Seg. William Carney, won the medal of honor for their efforts during the battle.

South Carolina was the first state to secede from the Union on December 20, 1860, and by February 1861, six other states had joined them. With their secession, each state demanded that the United States turn over Federal property to the state, such as Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor. The Lincoln administration refused. Early on April 12, 1861, Confederate forces opened fire on the fort, and by mid-afternoon the next day, Federal forces surrendered the fort.

To the South, Charleston, and Fort Sumter, as the "birthplace" of Confederate independence and the site of the first victory of their new nation with the Battle of Fort Sumter. To the North, Charleston symbolized secession. The Union Army hoped that if Federal forces could force the city to surrender, they could cause the entire Confederacy to surrender.

At the onset of the Civil War, African Americans could not officially fight in the Union Army. However, African American Union regiments were still raised in Louisiana, South Carolina, and Kansas in the Fall of 1862. The First, Second, and Third Louisiana Native Guard were organized out of New Orleans. In South Carolina, the First South Carolina Infantry included men of African descent who participated in coastal expeditions during November of 1862. Additionally, the First Kansas Colored Infantry saw service at Island Mound, Missouri, in October of 1862, before officially mustering into service. African American men serving in these early forces demonstrated their fierce passion for freedom by taking up arms and fighting for Union, even when they often received very little support from the federal government.

On September 22, 1862, Abraham Lincoln issued the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation that stipulated that if the Southern states did not cease their rebellion by January 1st of the next year, then the Emancipation Proclamation would go into effect. When the South did not surrender, the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect. This proclamation declared that all African Americans enslaved in states that had seceded from the Union were free. After this proclamation, the Union army began recruiting and enlisting African Americans and created the United States Colored Troops.

As African American soldiers entered the Union army, part of the public was worried about their ability to fight effectively. During battles like the Battle of Fort Wagner, African American soldiers proved their bravery in battle, their military prowess, and their courage in the face of the enemy.

Fort Wagner: Featured Resources

All battles of the Operations Against the Defenses of Charleston Campaign

Related Battles

5,000

1,800

1,515

174