Franklin

Second Battle of Franklin

Franklin, TN | Nov 30, 1864

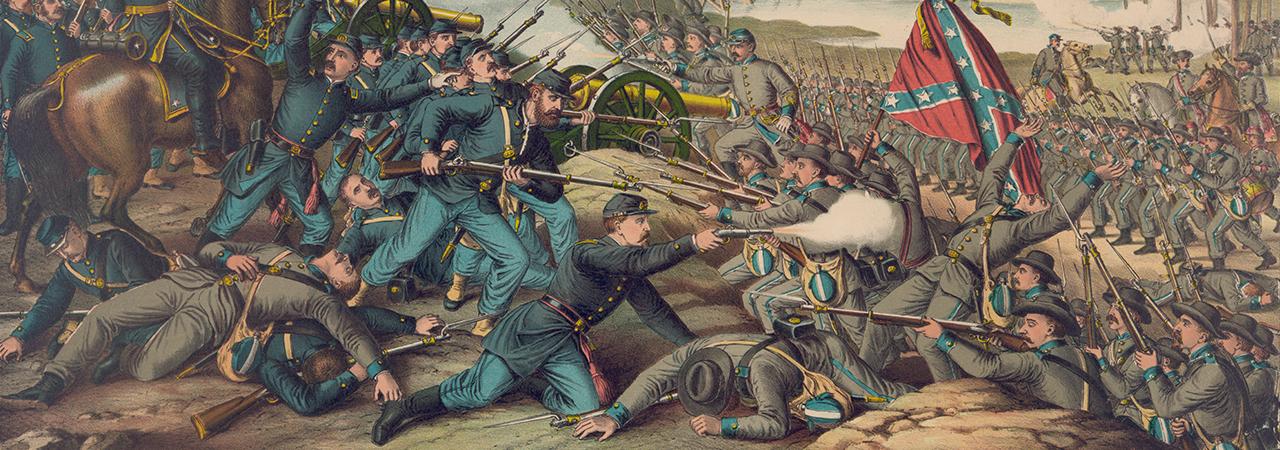

The scale of the Confederate charge at Franklin rivaled that of Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg. The action resulted in a disastrous defeat for the South and failed to prevent the Union army from advancing to Nashville.

How It Ended

Union victory. The devastating defeat of Gen. John Bell Hood’s Confederate troops in an ill-fated charge at Franklin, resulted in the loss of more than 6,000 Confederates, along with six generals and many other top commanders. The fighting force of the South’s Army of Tennessee was severely diminished, but Hood continued to chase victorious Union general John M. Schofield to Nashville.

In Context

After the fall of Atlanta on September 1, 1864, Gen. John Bell Hood and his 30,000-man army raced into Tennessee, hoping to divert Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s attention by threatening his supply base at Nashville. Sherman did not take the bait, and instead dispatched Maj. Gen. John Schofield’s Army of the Ohio, 30,000 strong, to protect Nashville while the rest of Sherman’s army simply left their supply line behind and marched to the Atlantic coast, forcibly securing whatever they needed to sustain themselves from the Confederate citizens in their path. Twenty-five thousand Union soldiers under Maj. Gen. George Thomas were entrenched in Nashville. If Schofield could reach them before Hood, he would command a numerical advantage on the battlefield. Hood’s hopes for a successful campaign rested on defeating Schofield before the two forces joined.

After a missed opportunity at the Battle of Spring Hill on November 29, Hood pursued Schofield to the town of Franklin, where the Confederate general led an assault on November 30 that cost him 20 percent of his men and allowed Schofield to progress toward Nashville.

On November 28, after a month of sparring along the Tennessee and the Duck rivers, Hood manages to divide Schofield’s army and surround a portion of it in the riverside town of Columbia, Tennessee. But miscommunication and confusion in the Confederate ranks result in the escape of Schofield’s forces. After what becomes known as the Battle of Spring Hill, Schofield withdraws his soldiers to Franklin, mostly unscathed. The catastrophic mistake infuriates Hood. He orders a pursuit to Franklin, where he will have one more chance to attack the Federals before they reach Nashville.

But Franklin does not offer the same possibilities as Spring Hill. Instead of fighting a surrounded and outnumbered enemy, the 20,000 Confederates at Franklin face a frontal assault over two miles of open ground against a roughly equal foe entrenched behind three lines of breastworks and abatis. Unmoved by his lieutenants’ objections, Hood orders the charge.

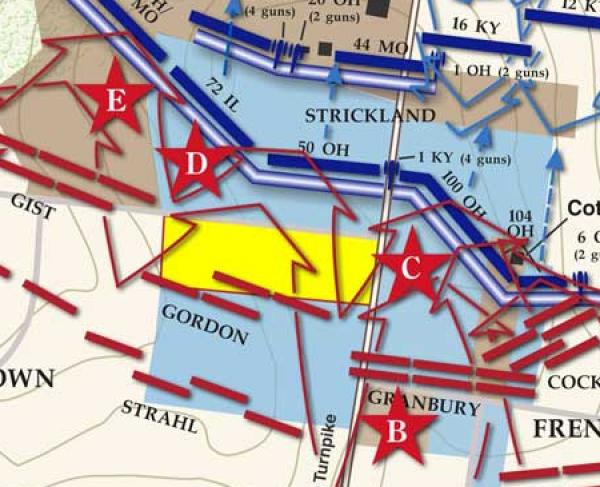

November 30. The two-mile-long Confederate line steps off at 4:00 p.m. The advance is immediately torn by scores of Union cannon. Hood has only one battery positioned to counter the enemy fire. Nevertheless, the line sweeps forward and quickly overlaps and overwhelms two brigades of Brig. Gen. George Wagner’s division, which holds a doubtful position half a mile in front of the main line. Charging and yelling mere yards behind Wagner’s broken men, the Confederates in the center are able to cross the last half mile of their assault largely unopposed by the riflemen behind the breastworks, who are unwilling to shoot their friends amidst their enemies. As a result, the Confederates slam into the Union center with full momentum and splinter the defenders around the Carter House.

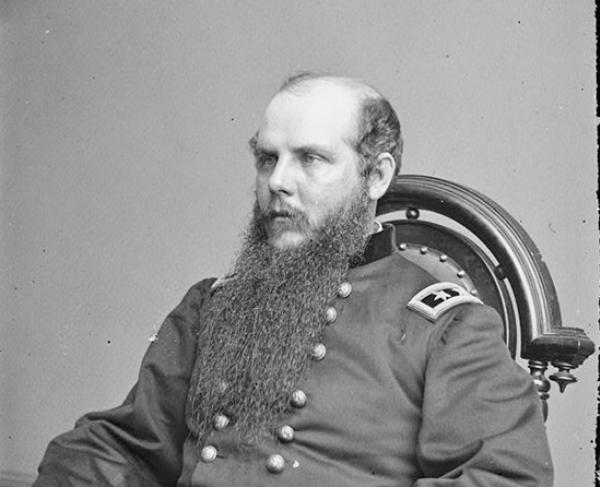

Thousands of men surge into a deadly vortex of combat with shovels, bayonets, sabers, and pistols in the Carter gardens. The Union line might break completely if not for the quick reaction of Col. Emerson Opdycke of Wagner’s division, who disobeys orders to join the first exposed line and instead deploys his men about 200 yards behind the Carter House. He hurls his command forward into the breach and prevents full-scale disaster.

Meanwhile, Maj. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest forces a crossing of the Harpeth River at Hughes’s Ford and threatens to turn the Union left flank. Union cavalry commander Brig. Gen. James Wilson reacts quickly and sends his horsemen pounding toward the ford to confront the Rebels. After a brief dismounted firefight, Wilson’s troopers charge, covered by a hail of repeating rifle fire. Although Forrest’s men outnumbered the Federals, they are outgunned by the seven-shot Spencers. They withdraw back across the Harpeth.

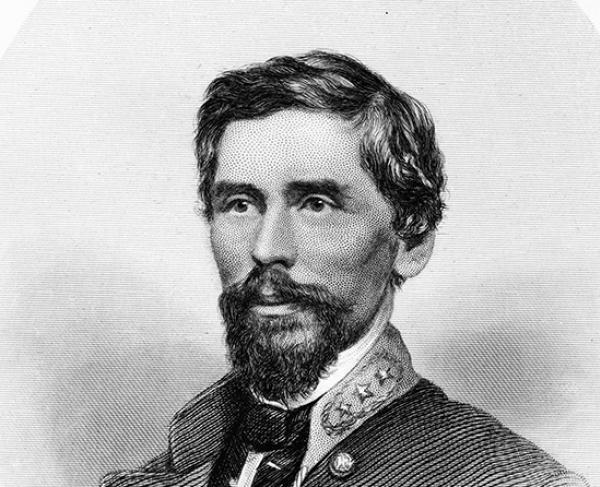

On the opposite bank of the river, the soldiers of Confederate general A.P. Stewart’s corps crash against the western portion of the main line. Swept by musketry and enfiladed by artillery, the Confederates press on until they reach a tall abatis of Osage-orange timber. They have no choice but to try to climb and crack their way through the strong branches under murderous point-blank fire. Union soldiers would later write about the nightmarish sight of the tangle filled with twisted and contorted corpses. The Confederates retreat, reform, and renew the attack as many as six times, but cannot dislodge the Union defenders. As the sun sets, with his attempt on the right stalled and the hand-to-hand fighting in the center raging into its third hour, Hood sends forward his left wing. The men of Gen. Benjamin Cheatham’s corps, advancing by torchlight, soon became separated and disorganized. When they stumble within range of the Union works, the rolling stabs of musket flashes fell men by the score. The soldiers reach as far as a small locust grove less than 50 yards from the breastworks before they finally withdraw with severe losses, having done little damage to the enemy. The Confederates also fall back in the center, leaving thousands of dead and wounded in the two acres of the Carter gardens. As the pressure lifts, Schofield withdraws his army to Nashville.

2,326

6,252

The Battle of Franklin decimates the Army of Tennessee. Around 8,500 men become casualties on both sides, roughly 6,000 of them Confederates. Fourteen Southern commanders become casualties, more than in any other battle of the war. Even so, Hood, with his diminished army, doggedly pursues Schofield to fight again at the Battle of Nashville.

By defying his superior officer’s command to take a position on the front lines that provided no cover, Opdycke was able to keep his men back until they were needed to plug a gap in the Union defense. This maneuver possibly saved the day for the Union at Franklin.

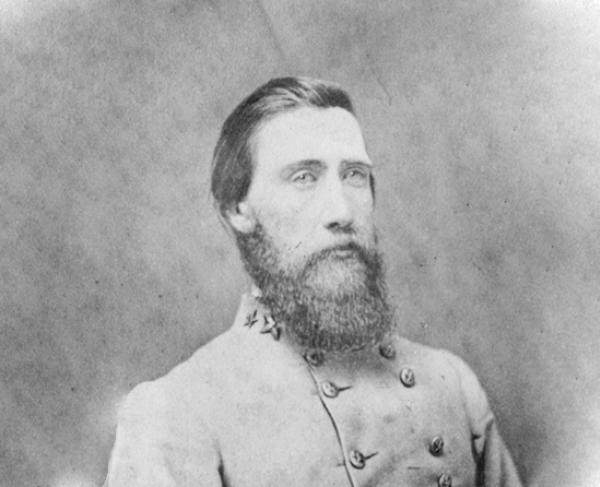

As the Battle of Franklin got underway on November 30, 1864, Brig. Gen. George Wagner ordered Opdycke to place his men in position to extend the Union line, but Opdycke vehemently refused. He considered Wagner’s line to be exposed and impossible to defend. The two officers argued back and forth. Eventually, Wagner gave up and told Opdycke that he was in reserve and should fight wherever he was needed. Later that day, two Confederate divisions under major generals John Brown and Patrick Cleburne struck the Union defenses, driving the two brigades back and opening a hole in the center. Opdycke’s brigade charged forward to help seal the gap. Much of the fighting was hand to hand and Opdycke himself fought on foot after his horse was shot out from under him. The counterattack was successful, and the center of the Union line held.

After the battle, Opdycke explained his actions in this report:

HDQRS. FIRST BRIG., SECOND DIV., 4TH ARMY CORPS,

Nashville, Tenn., December 5, 1864.

. . . General Wagner was with me in person, and ordered me to fight when and where I thought I should be most needed without further orders. The men got coffee, and at about 4 p.m. General Cox sent me a request to have my brigade ready, and I received no other orders till after the battle. I was familiar with the whole ground and knew that Carter’s hill was the key to it all. The fighting was now heavy, and I commenced moving the command to the left of the pike for greater security to the men and for easier maneuvering in case of need. While thus moving a most horrible stampede of our front troops came surging and rushing back past Carter’s house, extending to the right and left of the pike. I at first thought them only the Second and Third Brigades of our division that were left nearly a quarter of a mile to the front with orders to fall back: but I soon saw that the troops at the main works had left them. When I gave the order “First Brigade, forward to the works,” bayonets came down to a charge, the yell was raised, and the regiments rushed most grandly forward, carrying many stragglers back with them. We deployed as we charged, which took us up in echelon forward on the center, Colonel Smith’s two regiments leading.

An offensive military maneuver in which soldiers advance in large, tight formations toward well-fortified positions seems counter-intuitive and self-destructive, but Civil War troops who were ordered to charge were simply practicing the modern military tactics of the time. In addition to the charge at Franklin on November 30, 1864—the deadliest charge for general officers—the following are some of the most memorable and costliest frontal assaults of the Civil War.

- The Largest Assault of the Civil War: General Lee’s attack at Gaines’ Mill, June 27, 1862

- The Largest Flank Attack of the Civil War: Stonewall Jackson’s assault at Chancellorsville, May 2, 1863

- The Best-known and Most Mythologized Assault of the Civil War: Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg, July 3, 1863

- The Most Fortuitous Charge of the Civil War: General Longstreet’s attack at Chickamauga, September 20, 1863

- The Most Compact Large-Scale Attack of the Civil War: General Hancock’s assault at Spotsylvania, May 12, 1864

- The Largest Cavalry Charge of the Civil War: Torbert’s grand charge at Third Winchester, September 19, 1864

- The Most Consequential Attack of the Civil War: Horatio Wright’s Breakthrough at Petersburg, April 2, 1865

Franklin: Featured Resources

All battles of the Franklin-Nashville Campaign - September - December 1864

Related Battles

30,000

33,000

2,326

6,252