Second Manassas

Second Bull Run, Brawner's Farm

Prince William and Fairfax Counties, VA | Aug 28 - 30, 1862

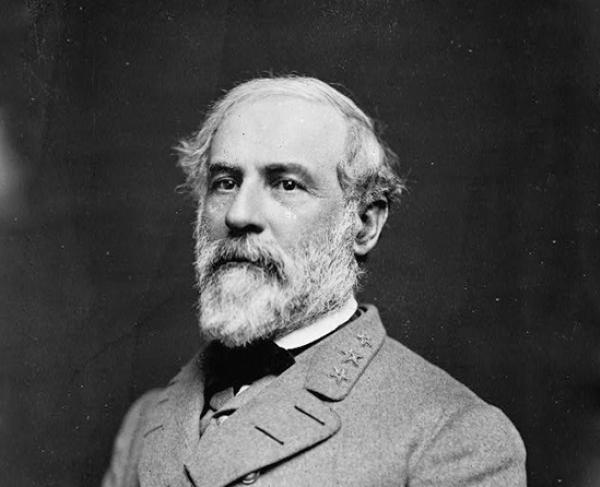

At Second Manassas, Gen. Robert E. Lee’s Confederate army defeated Union forces under Maj. Gen. John Pope, hastening the Federals’ retreat back toward their defenses in Washington and allowing Lee to lead his army across the Potomac River into the North.

How it ended

Confederate victory. The Union was crushed, and the army was driven back to Bull Run. Only an effective Union rearguard action prevented a replay of the First Manassas disaster. Second Manassas proved to be the deciding battle in the Civil War campaign waged between Union and Confederate armies in northern Virginia in 1862.

In context

One year after their stunning victory at the First Battle of Manassas in July 1861, Confederate prospects were uncertain. General Ulysses S. Grant was keeping the Rebels at bay in the West. In the East, Gen. George B. McClellan was threatening the Confederate capital at Richmond with the largest army ever assembled in North America. Three Union forces in the Shenandoah Valley were attempting to move south to support McClellan’s invasion, but their progress was continually impeded. Frustrated by the failure of those troops to gain ground, President Abraham Lincoln formed the Army of Virginia in June 1862 and appointed Maj. Gen. John Pope to command it.

The Lincoln administration gave Pope the dual task of shielding Washington and operating northwest of Richmond to take pressure off McClellan’s army. But Pope’s defeat at Second Manassas was a setback. This second loss for the Union near the battlefield at Bull Run resulted in Pope’s dismissal from command and Lee’s march northward.

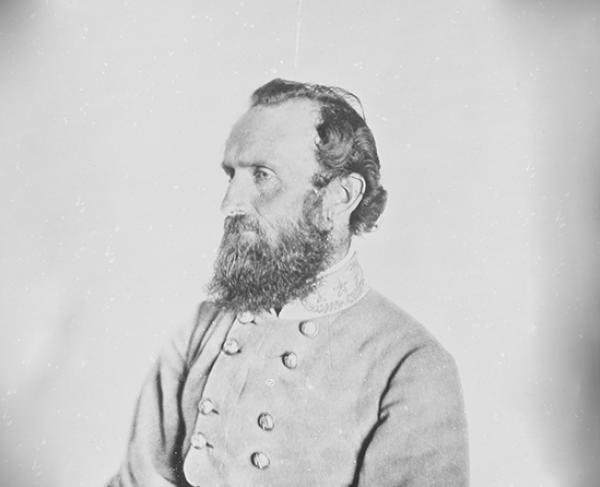

To counter Pope’s movement into central Virginia, Gen. Robert E. Lee sends Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson to Gordonsville on July 13. Jackson’s force crosses the Rapidan River and clashes with the vanguard of Pope’s army at Cedar Mountain, south of Culpeper, on August 9. Jackson’s narrow tactical victory proves sufficient to instill caution in the Union high command. The initiative shifts to Lee.

Confirming that the remainder of McClellan’s Army of the Potomac is departing the Virginia Peninsula southeast of Richmond to join forces with Pope in northern Virginia, Lee orders Lt. Gen. James Longstreet’s wing of the Army of Northern Virginia to join Jackson. Lee intends to destroy Pope before the bulk of McClellan’s reinforcements can arrive and outman the Confederates. Pope, however, foils Lee’s plans by withdrawing behind the Rappahannock River on August 19.

To lure Pope away from his defensive positions along the Rappahannock, Lee makes a daring move. On August 25, he sends Jackson on a sweeping flank march around the Union right to gain its rear and sever Pope’s supply line. At sunset on August 26, Jackson’s forces complete a remarkable 55-mile march, striking the Orange and Alexandria Railroad at Bristoe Station and subsequently capturing Pope’s supply depot at Manassas Junction. As Lee had anticipated, Pope abandons the Rappahannock line to pursue Jackson, while Lee circles around to bring up Longstreet’s half of the Confederate army. After fending off the advance of Pope’s army near Bristoe, Jackson torches the remaining Union supplies at Manassas Junction and slips away, taking up a position north of Groveton, near the old Bull Run battlefield.

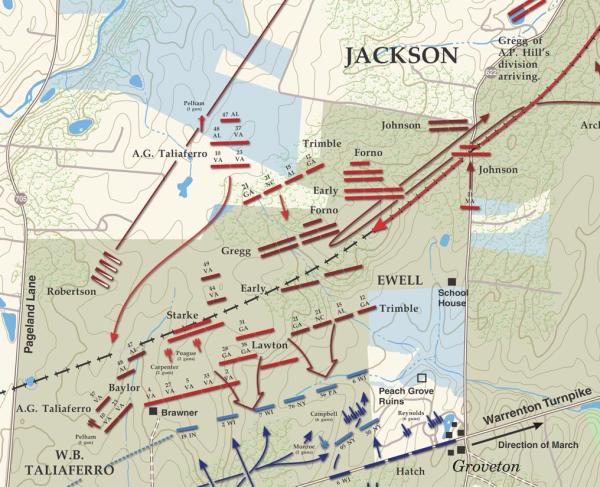

August 28. Alerted that Lee and Longstreet had reached Thoroughfare Gap and would arrive the following day, Jackson strikes a lone Union division on the Warrenton Turnpike, resulting in a fierce engagement at the Brawner Farm that evening.

August 29. Believing that Jackson is attempting to escape, Pope directs his scattered forces to converge on the Confederate position. Throughout the day, Union forces make piecemeal attacks on Jackson’s line, positioned along an unfinished railroad, while Pope awaits a flanking movement by his subordinate, Maj. Gen. Fitz John Porter. Although the Union assaults pierce Jackson’s line on several occasions, the attackers are repulsed each time. Late in the morning, Lee arrives on the field with Longstreet’s command, taking position on Jackson’s right and blocking Porter’s advance. Lee hopes to unleash Longstreet on the vulnerable Union left, but Longstreet convinces the Confederate commander to hold off.

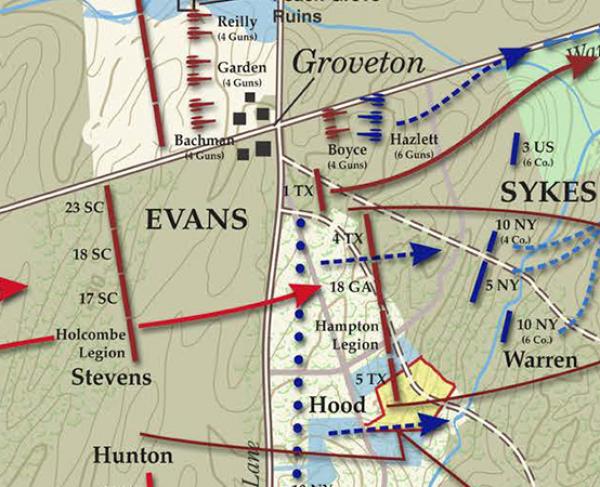

August 30. Pope receives conflicting intelligence and weighs his options. Mistakenly convinced that the Confederates are retreating, the Union commander orders a pursuit near midday, but the advance quickly ends when skirmishers encounter Jackson’s forces still ensconced behind the unfinished railroad. Pope, still undeterred, shifts to a major assault on Jackson’s line. Porter’s corps and Brig. Gen. John Hatch’s division attack Jackson’s right at the “Deep Cut,” an excavated section of the railroad grade. However, with ample artillery support, the Confederate defenders repulse the attack.

Lee and Longstreet seize the initiative and launch a massive counterattack against the Union left. Longstreet’s wing, reinforced by Lee and nearly 30,000 strong, sweep eastward toward Henry Hill, where the Confederates hope to cut off Pope’s escape. Union forces mount a tenacious defense on Chinn Ridge, which buys time for Pope to shift enough troops onto Henry Hill and stave off disaster. The Union lines on Henry Hill hold as the Confederate counterattack stalls before dusk. After dark, Pope pulls his beaten army off the field and retreats across Bull Run.

14,462

7,387

Despite heavy Confederate casualties, Second Manassas is a decisive victory for the Rebels. Lee pulled off a strategic offensive against an enemy force much greater than his own. On September 5, Lee crosses the Potomac River into western Maryland and heads north. McClellan unites his army with the Army of Virginia and marches northwest to block Lee’s invasion. On September 17, Lee and McClellan clash in the Battle of Antietam, the costliest single day of fighting in American history.

The Second Battle of Manassas was larger in scale and greatly exceeded the number of casualties than the First Battle of Manassas, which was fought on the same ground in July 1861. So much had changed in a year. At the first battle, when the war was young, both Union and Confederate soldiers marched eagerly and innocently into a conflict they thought would be short and victorious. Neither preconception turned out to be true. The First Battle of Manassas saw more than 5,000 casualties, including nearly 900 dead. The nation was shocked by the carnage. The Union was stunned by the stinging defeat. Lincoln’s hope for an easy 90-day victory was shattered.

The armies who met at the Second Battle of Manassas in late August 1862 were more experienced. They were battle scarred and hardened. The soldiers had none of the naive enthusiasm shown by their peers in 1861. As the Civil War stretched into its second year, the battles became deadlier and bloodier. The forces were larger, the troops better trained, the officers more prepared, and the tactics more ruthless and proficient. New developments in weaponry made warfare more dangerous, as rifles and artillery could be fired with greater precision. The human toll was greater, with almost 14,000 Union and more than 8,000 Confederate casualties. The exhausted troops showed little remorse toward the enemy. They were numbed by the atrocities they had witnessed.

John Pope’s ill-fated decisions at Second Manassas had personal consequences. His arrogance before the battle only served to exacerbate the sting of defeat. After he was named commander of the newly formed Army of Virginia on June 26, 1862, he lectured his troops:

This attempt to boost morale only served to insult his corps commanders, who felt his critical words targeted them.

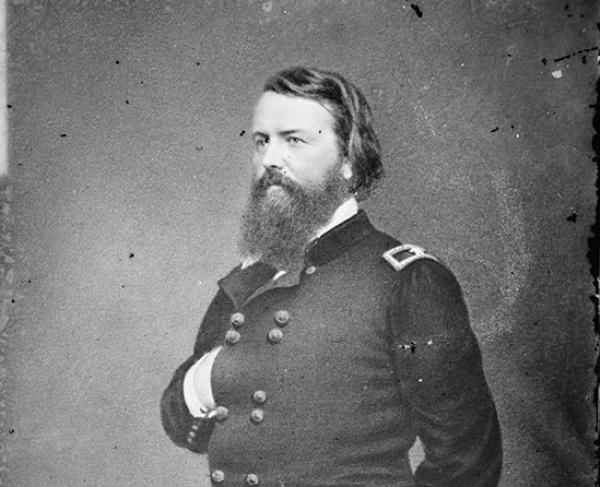

Pope was a well-trained and capable officer. Like many other Civil War generals, he attended the United States Military Academy at West Point and served in the Mexican-American War. Before the Civil War he had a job surveying potential southern routes for the First Transcontinental Railroad. In 1861, he was appointed as a brigadier general in the Union army and had several successes early in the war, leading Lincoln to select him to command the Army of Virginia in 1862.

After Pope’s failure at Second Manassas, Abraham Lincoln commented, “Pope did well, but there was an army prejudice against him, and it was necessary he should leave. We had the enemy in our hands on Friday and if our generals, who were vexed with Pope, had done their duty…all of our present difficulties and reverses have been brought upon us by these quarrels of the generals.” So, in addition to losing almost 14,000 men in battle at Second Manassas, Pope lost his command of the Army of Virginia as well as his reputation. He was sent to the Army's Department of the Northwest for the remainder of the Civil War.

Second Manassas: Featured Resources

All battles of the Northern Virginia Campaign

Related Battles

70,000

55,000

14,462

7,387